The Fraying Edge: Limits Of The Army’s Global Network

Posted on

A soldier from the Army’s offensive cyber brigade during an exercise at Fort Lewis, Washington.

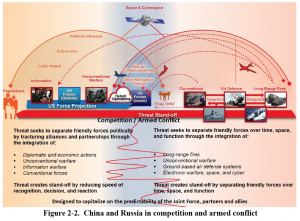

TECHNET AUGUSTA: As future soldiers hunker in foxholes, hiding from spy drones and smart bombs, they could really use some real-time intel to plan their next move. But how do you get them access to the AI-curated big data on centralized cloud servers back in the continental United States? Until someone figures out how to run fiber optic cable to every squad, command post, tank, and helicopter, frontline forces must rely on wireless — which means radio and, maybe, one day lasers. Bandwidth is going to be a problem.

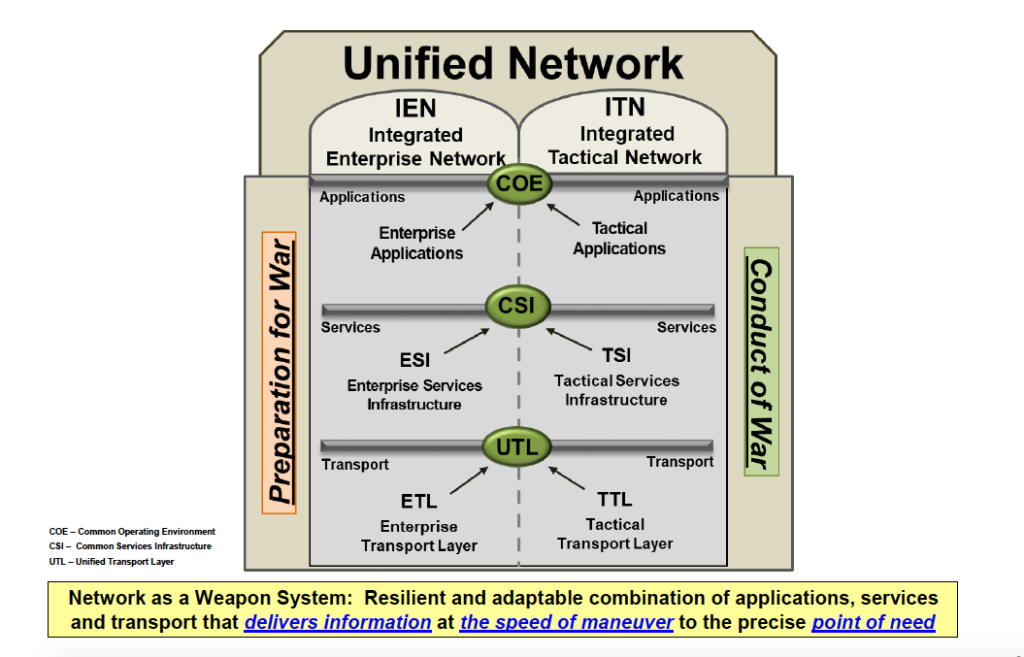

The Pentagon increasingly sees ubiquitous big data, stored and accessed through cloud computing, as a key to victory. The Army, in particular, has pushed to connect, and ultimately combine, its enterprise network — mostly fiber optic cables on safe, stationary bases in the US — to its tactical network — which must use wireless satellite and surface-to-surface links to units on the move and in harm’s way.

At last week’s AFCEA TechNet conference in Augusta, just outside the Army’s cyber center at Fort Gordon, I heard a lot of enthusiasm for converging enterprise and tactical networks. I also heard a lot of frank acknowledgment that it was hard.

But the closer someone was to the gritty technical details of tactical networks, it seemed, the greater their reservations. The farther from the foxhole, the greater the optimism.

The Army’s plan to integrate its enterprise (homebase) and tactical (battlefield) networks.

One Network To Rule Them All?

“From the tactical to the enterprise, we have a concept of the unified network,” the Army’s deputy CIO, Gregory Garcia, told the conference. Using every available means from local commercial networks to satellites, “we get through regional hubs into the enterprise, into clouds,” he said. “Reliable, seamless, trusted communications in any environment: That’s a really important goal for us.”

“Sydney, it’s one network,” said Maj. Gen. Garrett Yee, an Army signals officer who now serves as assistant director for the joint Defense Information Services Agency, the Pentagon enterprise-network provider par excellence. Right now, “it’s a lot of different pieces of the network,” he acknowledged, “but it’s all converging into a single unified/federated/whatever term you want to use network, where it’s all connected end-to-end, from the desktop to the tactical edge.

Maj. Gen. Garrett Yee

“As long as you have connectivity at the tactical edge, which we do in various ways — through satellite … fiber… microwave LAN [Local Area Network] — as long as you have connectivity for [data] transport, you can deliver services,” Yee told me after a TechNet panel.

Now, if one mode is disrupted or compromised, the network needs the capability to switch quickly to another. Army radio operators traditionally plan to have three backup channels available for their main link, a principle called PACE: Primary, Alternate, Contingency, Emergency. While most civilian networks can’t afford so much redundancy, it can be built into military ones, potentially with automated switching (“fail over”) to move from one broken connection to the next.

The end result, Yee told me, is that forward-deployed troops will be able to access DISA systems like the MilDrive cloud or SAFE file transfer, their identity confirmed by new endpoint security checks like miniaturized biometrics.

But with intervening terrain, technical glitches, and enemy jamming all disrupting battlefield wireless, I said, you can’t guarantee access all the way forward.

“Yes, you can,” Yee told me. No, frontline units won’t be able to access all the data all the time, but so-called distributed or hybrid cloud computing caches crucial data in nodes all over the network — the JEDI program envisions backpack mini-servers — instead of just pooling it all in a few massive data centers. Think of visiting your local library instead of going to the Library of Congress all the time.

“It may not be the whole repository of what might be in the data center back at home station,” Yee said, “but we have some instance of capability forward so you have what you need when you need it, even in a DIL [disconnected, intermittent and limited communications] environment.”

So how do you choose what subset of big data is copied to that local cache?

“Therein lies the work that needs to be done,” Yee said. “At the tactical edge it’s a limited amount of capability that you’re really looking for” — troops fighting in Afghanistan or the Baltics probably don’t need hi-res maps of South Africa, for instance, or the latest payroll figures — “so you’re not going to bring the whole server room forward, you bring what you need.”

An Army soldier sets up a highband antenna in Afghanistan.

Physics Strikes Back

If you listen to the Army’s top buyer of tactical network tech, however, the balance between confidence and caution starts to shift.

“There is one Army network,” said Maj. Gen. David Bassett, Program Executive Officer for Command, Control, & Communications – Tactical (PEO-C3T), in his remarks to the TechNet conference. But, he went on, “as we add data and analytics to our tactical networks, we’re really thinking through what data lives where and what transport provides forwards communication. Because when people use cloud, when they talk about enterprise services, there’s one huge assumption that underlies it all, and that assumption is fiber optic cable.

Maj. Gen. David Bassett

“As long as you’ve got fiber, life is easy,” Bassett said. “Sometimes when you’re deployed, you have fiber, if we’ve been there for a long time. But we’re not trying to produce a network for the last war. We’re trying to produce a network that supports our ability to fight and win against a peer adversary, and that means… systems that are designed to run on bandwidth that can be available and can be enduring if that bandwidth or that spectrum are challenged.

How do you make this work? The Army is systematically moving towards a single “unified network” uniting enterprise and tactical, said Col. Mark Parker. Until recently, he was the service’s Capability Manager for Networks & Services, with a central role in writing the official requirements.

“Back in 2017,” Parker told the conference, “we had trouble moving applications back and forth, we had trouble moving services and data back and forth. Sometimes you had trouble connecting those networks.” So, he said, then-Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley ordered a move to a single data-transport layer “that works everywhere.”

Getting to a single network immediately was “a leap a little too far,” Parker continued. The initial, most urgent step is just consolidating all the Army’s different war-zone systems into a single Integrated Tactical Network (ITN). Lagging slightly behind, by design, is the effort to unify disparate home-base IT systems into an Integrated Enterprise Network (IEN). The ITN and IEN should be solidly in place “in the next four or five years,” around 2023-2024, Parker said.

After that, the Army will continue updating both tactical and enterprise systems, all the while continually pushing them to use common standards and technologies. The two systems should converge he said, into a single Unified Network by 2028, the Army’s self-imposed deadline to get ready for high-tech Multi-Domain Operations.

SOURCE: Army Multi-Domain Operations Concept, December 2018.

“Then I’m just limited to how bandwidth I have…how much storage do I have, how many processing cycles do I have on the local computing power,” Parker said, “allowing the commander to choose what services and information can be positioned where.”

“At some point,” he warned, “you’re limited by physics.”

Having less bandwidth on the battlefield than at home base doesn’t just change how fast you can download all the same stuff. It changes how your applications work and, in many cases, what software you can get to work at all.

“All these things that are done at the enterprise [level] don’t necessarily work in the tactical environment. That’s the bottom line,” said Brian Lyttle, chief of cybersecurity at the Army’s C5ISR Center. “Enterprise applications tend to be very chatty” — that is, they constantly exchange large amounts of data over the network — “so frankly they don’t tend to work very well when they get pushed down” to low-bandwidth, intermittently available tactical connections, he warned.

What’s more, Lyttle told the conference, most enterprise applications today tend to be both highly complex and narrowly focused on a particular task. That means they take a lot of specially trained personnel to operate, a luxury not available in frontline command posts, let alone the foxhole.

Frontline hardware has to be different, too: more rugged, more compact, less hungry for electrical power, less complex to use. “We take everything with us,” Lyttle said. “We don’t count on any kind of infrastructure.”

“The PMs [acquisition project managers] and soldiers have told me it’s got to be easy to operate, easy to understand,” Lyttle continued. Troops have to be able to use it, he said, when “it’s cold; my fingers don’t work; I’ve only gotten three hours’ worth of sleep; I’m low on water.”

That’s not the kind of user-interface problem the typical cubicle dweller faces back in the US.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.