SecAF Wilson Takes Charge, Calls For 24% Boost In Squadrons

Posted on

Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson at the Air Force Association Air Warfare Symposium in February 2018.

Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson laid down what will probably be the signature marker of her term as head of the Air Force, calling today at the Air Force Association conference for 74 new operational squadrons, including five more bomber squadrons, seven more special operations squadrons, 14 more tanker squadrons, seven more fighter squadrons, and 22 more Command and Control Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance squadrons. But, she noted of the larger Air Force she says the nation needs: “It’s not just larger; the way we fight will be different.” Dave Deptula, head of AFA’s Mitchell Institute, analyzes Wilson’s commitment below. Read on! The Editor.

Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson speech opening the Air Force Association’s annual conference today was fundamentally different than past leadership speeches. Wilson articulated what the Air Force actually needs to meet the demands of the nation’s security strategy—something that has not happened in decades.

When Secretary Wilson and Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Goldfein testified before Congress in 2017, they issued a stark warning: “…the Air Force is too small for the missions demanded of it and it is unlikely that the need for air and space power will diminish significantly in the coming decade.” Further amplifying these challenging circumstances, they said: “… potential adversaries are modernizing and innovating faster than we are, putting at risk America’s technological advantage in air and space.”

Nor were the secretary and chief alone in expressing their concerns about the future security environment, with Defense Secretary Jim Mattis explaining: “Our challenge is characterized by a decline in the long-standing rules-based international order, bringing with it a more volatile security environment than any I have experienced during my four decades of military service.”

KC-46A makes first contact & refuels an F-16C in January 2016

Secretary Wilson’s remarks today signify the service is set to take charge and align Air Force capacity to match real-world demand by adopting a force sizing construct tied to the National Security Strategy, not just arbitrary budget figures. This is a major step for the service, which has made “doing more with less” a way of life for nearly two decades.

The Air Force’s erosion can be traced back to the end of the Cold War, when a quest for a peace dividend saw aircraft and personnel shed in a rapid fashion. The post-9/11 era unleashed a dominant focus on occupation and attrition-based warfare priorities. Leaders seeking to prepare for a broader spectrum of threats relating to America’s global interests were marginalized, with then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates explaining in a 2008 speech: “I have noticed too much of a tendency towards what might be called ‘next-war-itis’ — the propensity of much of the defense establishment to be in favor of what might be needed in a future conflict.” The problem with his approach is that the future is now. On top of this, sequestration and multiple continuing resolutions further eroded a precarious set of aerospace capabilities. As it presently stands, America’s Air Force operates the smallest and oldest set of capabilities it has ever fielded going back to the creation of the service in 1947—312 operational squadrons today vice 401 at the end of the Cold War.

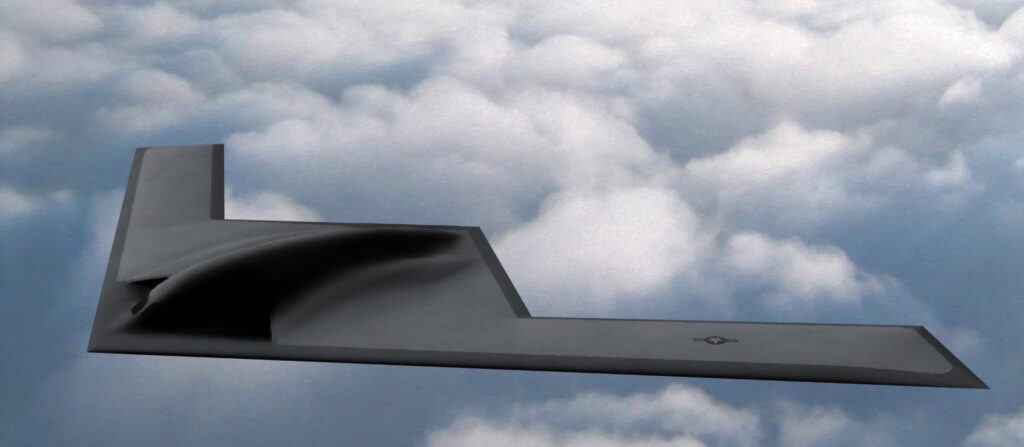

B-21 Raider artist rendering

The time for change cannot come soon enough. The world is an increasingly dangerous, complex place and US priorities ar at risk. This demands a robust toolkit to empower smart options. As the late Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Sen. John McCain declared in his 2017 defense whitepaper Restoring American Power, Recommendations for the FY 2018-FY 2022 Defense Budget: “We now face, at once, a persistent war against terrorist enemies and a new era of great power competition. The wide margin for error that America once enjoyed is gone.”

Proof of this conclusion lies with Russia’s increased aggression in places like Ukraine and Syria; China’s militarization of the South China Sea and beyond; North Korean and Iranian pursuit of robust nuclear arsenals; the continued strength of non-state actors like the Islamic State, Al Shabab, and Al Qaeda; and new threats posed in domains like cyberspace and outer space.

To handle these challenges, America’s senior leaders and top combat commanders require a broad range of options. This means American Airmen must come to the table with options that maximize the advantages of global vigilance, global reach, and global power. These functions are not simply facets of a catch phrase—they represent the core functions of the Air Force that allow the projection of strength, without the undue exposure of vulnerability. Said another way, if you did not like the results of occupation and attrition warfare over the past seventeen years, you might want to revisit aerospace-centric strategies.

Aerospace power missions may take the form of delivering relief supplies to a humanitarian disaster in a matter of hours, not days or weeks. Circumstances could also see long range strike bombers eliminating crucial targets deep behind enemy lines whose destruction yields an outsized impact on the course of a conflict. Securing air superiority is a pre-requisite for any modern military campaign. It could also involve vital command and control functions that see joint competencies knitted together in a real-time fashion to put the right types of assets in the right time and place to best achieve mission objectives.

One thing is certain, to successfully execute this panoply of missions in the context of our nation’s security strategy, capacity is required. It does not matter how advanced America’s aerospace capabilities might be if they are too small to meet fundamental mission demand. A combat aircraft cannot be two places at the same time. A base set of targets must be struck in rapid fashion. Logistics lines need to flow at a specified rate. Intelligence , surveillance, and reconnaissance must meet the extreme demands of nnmodern operations. With a return to peer competition as the dominant sizing factor in the security environment, does anyone honestly think 20 B-2s, 187 F-22s, and a handful of F-35s are enough combat capacity? The answer is clearly no.

F-22 Raptor

Urgency to act now is surging because the advanced nature of modern aerospace capabilities results in long lead times to build capacity, whether hardware or airmen to operate and sustain the hardware . Just look at the B-21—even with the involvement of the rapid capability office, a decade will likely transpire between contract award and operational fielding. Training crews to operate advanced aircraft takes years. The same holds true for space-based and cyber missions. The bottom line is that America’s ability to respond to a strategic surprise is not a quick-turn proposition. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld famously explained: “You go to war with the Army [Navy, Air Force, and Marines Corps] you have, not the Army [Navy, Air Force, and Marines Corps] you might want or wish to have at a later time.”

While the Secretary did not win any popularity points with that blunt assessment, he was exactly right. Modern conflict happens fast, is unpredictable, and requires decisive force. That is precisely why the Air Force has outlined today what its objective force structure needs to be—386 operational squadrons—to meet the demands outlined in our national security and military strategies.

These observations are not new or novel. Defense leaders have understood these factors for a long time. What is different about Secretary Wilson’s outlined approach is her willingness to put the Air Force’s challenges on the table so that Congress and others can understand the risk and prioritize necessary solutions. The era of robbing one mission area to bolster another must come to an end, for all Air Force competencies are important and require ample resources. Does anyone really think the Air Force wanted to retire, the U-2, Global Hawk, or the A-10? These were actions undertaken by leaders doing the best they could with far too little. The same could be said for space, the pilot shortfall, and low readiness rates. The discussion is really about resources. There comes a point where the cuts have to stop and the rebuilding has to begin. As Secretary Wilson has said, “It’s not defense that’s driving the deficit. I believe we can afford to defend the country.”

For those who question whether rebuilding capacity is affordable, consider that preventing war is always cheaper than fighting one. America’s competitors know that our defense resources are spread thin. This is exactly why Russia has engaged in aggressive behavior in Europe and the Middle East. It is why China has pursued a policy of territorial expansion in the Pacific. Such factors also explain why North Korea has been very aggressive in testing its nuclear strike technology. Adversaries know the US is self-deterred due to a lack of military capacity. This encourages hostile action because competitors think they might be able get away with pushing the boundaries of acceptable behavior. If you look at results in the Ukraine and Chinese manmade islands in the Pacific, this calculation appears to have paid off. However, such actions are exceedingly counter to American interests. The best way to stop this behavior is by deterring it before it occurs through a robust set of capabilities. That’s why Secretary Wilson’s plan to secure the Air Force American needs is so important.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.