Army Insists 1,000-Mile Missiles Won’t Breach INF Treaty

Posted on

WASHINGTON: The Army’s new “strategic fires” missiles won’t violate the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, a service spokesman assured me over the weekend. That’s despite the new chief of Army Futures Command, Gen. John “Mike” Murray, letting slip to Congress that at least one of the technologies the service is studying “could have a range of up to 1,000 nautical miles” (1,151 statue miles). That’s right in the 500-5,500 kilometer range (311 to 3,418 miles) the INF treaty forbids. How is this possible?

There are loopholes in the 1987 accord that newer technologies like hypersonics might shoot through, independent arms control experts told me. But, they warned, you might end up nitpicking the treaty to death.

Even though the Russians have already fielded some INF-violating weapons of their own, they’ve historically argued for a broad interpretation that would ban armed drones such as Predator and Reaper — not coincidentally, an area of major American advantage. So if the US sought an advantage (or at least to catch up) in hypersonics or cannon-launched missiles, the Russians might well claim the treaty was void and escalate by fielding new weapons of their own en masse.

The question is tricky, technical and requires precise wording. So it’s worth taking a close look at what the treaty says, what the Army has said, and what the experts think.

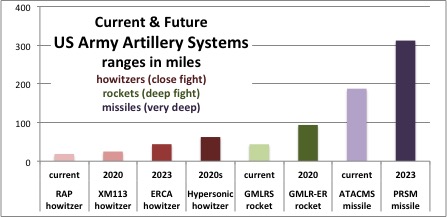

RAP: Rocket Assisted Projectile. ERCA: Extended Range Cannon Artillery. GMLRS: Guided Multiple-Launch Rocket System. ATACMS: Army Tactical Missile System. PRSM: Precision Strike Missile.

SOURCE: US Army.

The Army

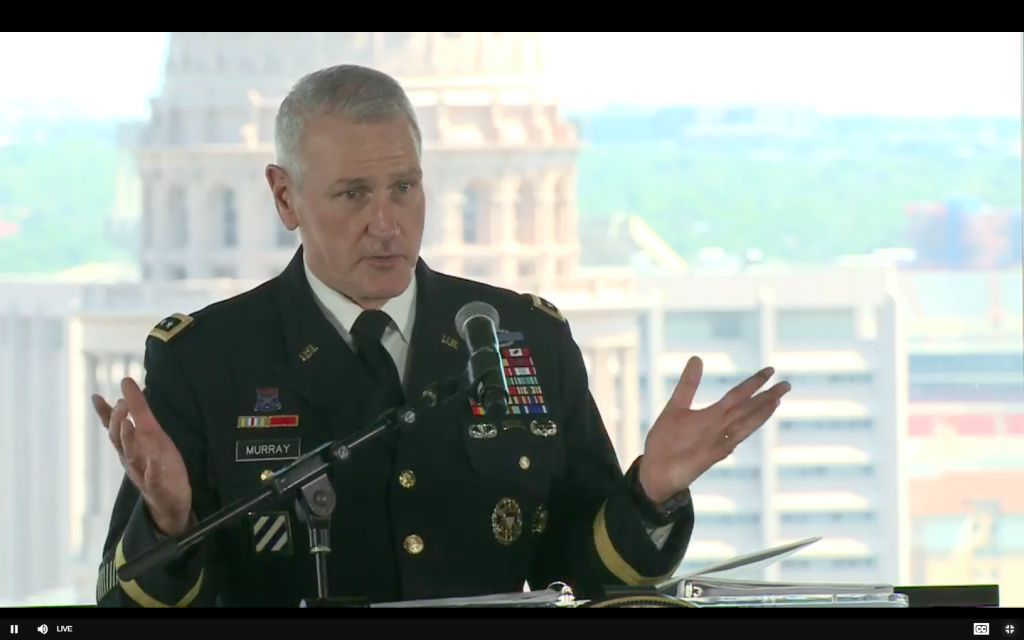

While his subordinates have studiously avoided any specific numbers, Army Futures Command’s chief, Gen. John Murray, gave the 1,000-mile figure during a hearing Thursday of the House Armed Services readiness subcommittee:

“(For) our strategic fires, we’re looking very hard and starting down the path of hypersonics and then also looking at what we call the Strategic Long Range Cannon, which conceivably could have a range of up to 1,000 nautical miles,” Murray said.

It’s worth putting this remark into context. Murray was summarizing Army improvements across “all three echelons of fires”:

- Tactical fires, i.e. howitzers, which the Army plans to upgrade to Extended Range Cannon Artillery (ERCA) with a 44-mile or even 63-mile range by using a longer barrel and improved, possibly hypersonic Rocket-Assisted Projectiles (RAP).

- Operational fires, i.e. missiles, where the Army wants to field a new Precision Strike Missile (PRSM) with a range of 499 km, “only limited by the INF Treaty,” as Murray put it Thursday. PRSM would replace the Army Tactical Missile System, ATACMS, which has a 188-mile range.

- Strategic fires, i.e. both a ground-launched hypersonic (Mach 5-plus) missile and Strategic Long-Range Cannon (SLRC) that uses a super-long barrel to fire precision-guided and probably rocket-boosted projectiles. The Army’s not had anything in this category since the INF Treaty forced it to retire its Pershing II missiles by 1991.

(We reported on the tactical and operational weapons earlier this year).

When I followed up with Murray’s spokesman, Col. Patrick Seiber, he continued the Army’s custom of not giving a number. A verbatim passage from our email exchange:

- Me: Is it now fair to say the Army is officially pursuing 1,000-mile ranges for Strategic Fires?

- Seiber: “The Army is developing capabilities to attack targets at strategic ranges. Our technology efforts prove that strategic ranges are possible and we may develop systems with the capability to defeat enemy anti-access/area denial systems in support of the joint force.”

- Me: Does the Army believe such weapons can be compliant with the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty?

- Seiber: “Yes.”

But, I asked, since presumably strategic fires go farther than tactical or operational fires, and the Army’s new Precision Strike Missile — an operational missile — goes 499 km, is it safe to assume that a strategic fires system must go at least 500 km?

“I think that is fair,” Col. Seiber replied.

Another way of putting it: If, as Gen. Murray notes, PRSM’s maximum range of 499 km is “only limited by the INF Treaty,” anything longer – such as strategic fires – would not be limited by the treaty. So how is this supposed to work?

ATACMS missile launch. The Army Tactical Missile System has a range of about 188 miles, much shorter than its planned successors.

The Treaty

For a document written by diplomats, the text of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty can be commendably direct: “each Party shall eliminate its intermediate-range and shorter-range missiles…The term ‘ballistic missile‘ means a missile that has a ballistic trajectory over most of its flight path (and) the term ‘cruise missile‘ means an unmanned, self-propelled vehicle that sustains flight through the use of aerodynamic lift over most of its flight path.”

On the other hand, the treaty only covers missiles that are “ground-launched,” without actually defining what that means. Some commentators have suggested the Army fire the missiles in question from a barge, making them technically “water-launched” – although this would lose the main advantage of a ground-based weapon, which is the ability to hide from attack underground or in dense terrain (rivers being flat). It’s also conceivable the Army could launch something from one of its helicopters or even its small fleet of fixed-wing aircraft, although that would put severe limits not only on hiding but also on maximum size – and be much less effective than just having the Air Force do it from a proper strike aircraft.

The potential loophole the arms control experts pointed out to us is subtler. The treaty bans any missile that either “has a ballistic trajectory” or “sustains flight through the use of aerodynamic lift,” in either case “over most of its flight path.” It’s possible that a hypersonic missile, especially one that skipped and out of its atmosphere, wouldn’t spend enough of its flight time either ballistic or in the air (“us[ing] aerodynamic lift”) to count. While the experts didn’t address it directly, the same argument could be made for a cannon-launched projectile that started in a ballistic trajectory, switched to self-propulsion using aerodynamic lift, and then glided to the target.

“It’s not impossible,” said Lynn Rusten, a former State Department and NSC arms control expert now with the Nuclear Threat Initiative. “The treaty didn’t anticipate hypersonics and it’s possible a hypersonic flight path would not meet the definition of a ballistic missile or a cruise missile.”

“Right,” said Kingston Reif, director for disarmament at the Arms Control Association. In fact, he said, “the Obama administration argued at the time New START was being considering that strategic-ranged, conventionally armed, boost glide vehicles that don’t fly on a traditional ballistic trajectory would not be subject to the treaty.” But New START only applies to “nuclear armaments,” whereas the INF treaty (despite its name) also covers conventional weapons, like the ones the Army wants to build.

All told, “I’d need to review the treaty and I’d need a lot of info about the technical characteristics of the systems under consideration” — no doubt highly classified — “to make a judgment,” Rusten said. “That’s what the compliance review process is for. But it shouldn’t be a DoD-only process. They need to take it to State and NSC for interagency compliance review.”

(“We have discussed Army strategic fires and treaty compliance with OSD,” Seiber said. Note that’s the Office of the Secretary of Defense – not anyone outside the Pentagon).

Even if the US convinces itself it won’t violate the letter of the treaty, though, can the INF accord survive such a blow to its spirit?

Are they consistent with the spirit of the treaty or not? ” Rusten asked. “If you cared about preserving the treaty, you’d have that conversation.”

“Regardless of whether artillery or a HGV (hypersonic glide vehicle) over 500 km would violate the letter of the treaty, Russia would likely claim it as a violation, similar to the armed drone issue which Russia has raised,” Reif warned. “Ground-launched weapons with INF ranges that don’t neatly fit the definition of a ballistic or cruise missile in the treaty should logically be subjects of discussions in the Special Verification Commission to close off those routes to circumventing the purposes of the treaty. But this requires political will.”

We don’t face this dilemma immediately, because the treaty only applies to operational missiles: “R&D on noncompliant systems is not prohibited,” Reif noted. But given the Army’s urgent desire to upgrade its arsenal in the early 2020s, the time to think about this calmly will run out fast enough.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.