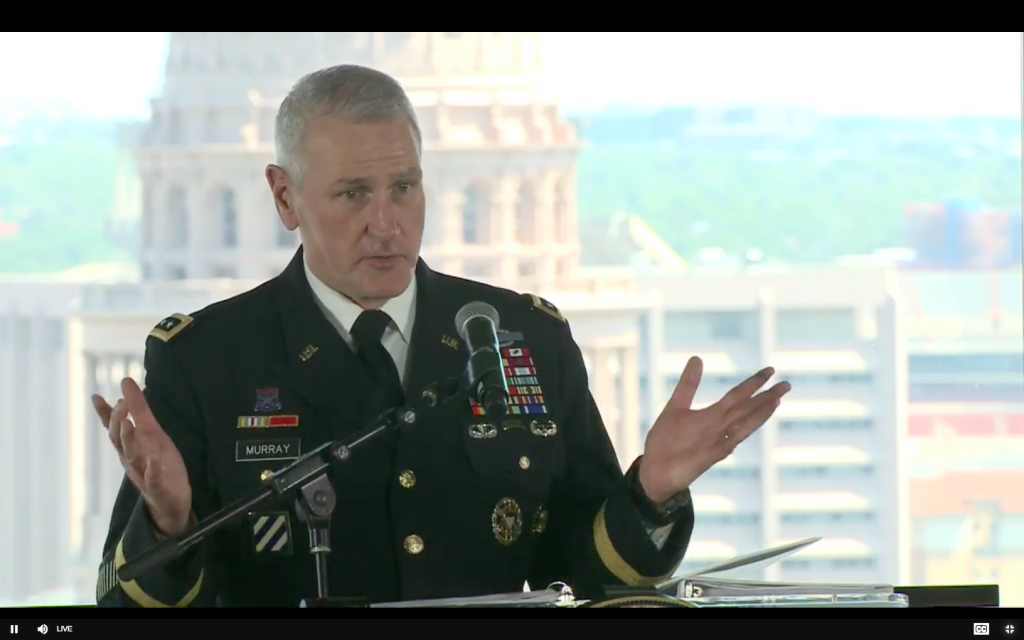

Failure IS An Option: Army Gen. Murray

Posted on

AUSA: “God help us, if, the first time something fails — and something will fail — we crush whoever it was … whoever’s responsible,” the Army’s four-star chief of modernization warned today.

“A culture that avoids risk at all costs,” Gen. Mike Murray said, means it takes too long to field new technology, if it makes it into service at all. Program managers and modernization team directors are the ones who’ll have to take risk to move faster, he said. “If we crush ’em, we’re never going to change that culture.

“It’s easy to say we want to become more accepting of risk. It’s easy to say we want to fail early and fail cheaply,” Murray warned officers, contractors, and retirees at the Association of the US Army‘s Arlington HQ this morning. “The proof will be in the pudding, because there will be a failure.”

Room For Failure

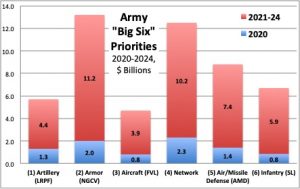

So, I asked Murray, can the Army’s overall modernization effort survive the failure of individual weapons programs? The service has identified some 31 key initiatives (not all of them formal acquisition programs of record), from hypersonic missiles to augmented-reality goggles. Those 31 initiatives form the base of a pyramid, with several supporting one of the Army’s six modernization priorities: artillery, armor, aviation, networks, air & missile defense, and soldier gear. The Big Six, in turn, provide the tools to wage the fast-paced form of future war known as Multi-Domain Operations. If you take away a block at the base, does the pyramid crumble? Or can the modernization effort survive the failure of one or more of those 31?

“I think so,” Murray responded. “In fact, I don’t think so. I know so.”

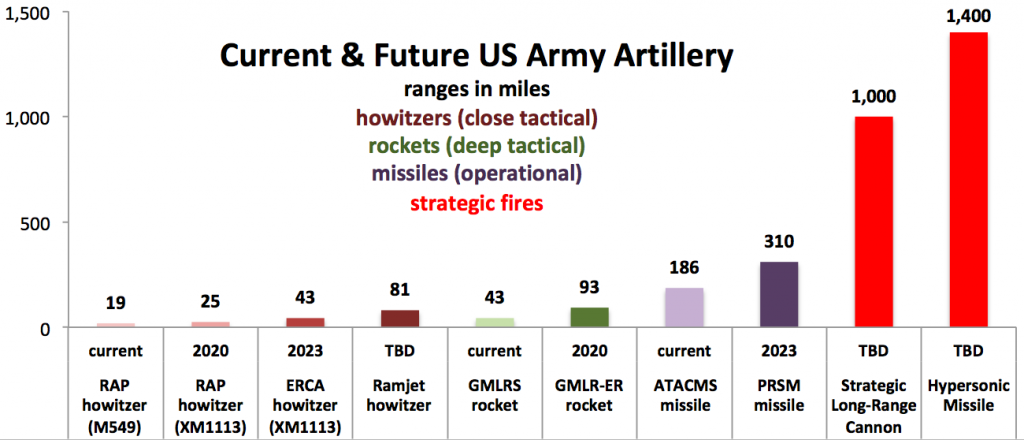

Yes, he acknowledged, there are interdependencies among the 31 initiatives, which need to fit together in an overall “operational architecture.” Consider long-range firepower, sensors, and networks, for example. We need, Murray said, “to make sure that if I can shoot 1,000 miles, I can also see 1,000 miles, that I can also pass targeting data back 1000 miles.”

That said, “Is there room for failures? Yes…. This concept does not count on any specific piece of capability,” Murray said. For example, “if the Strategic Long-Range Cannon does not deliver, we have hypersonics.”

RAP: Rocket Assisted Projectile (current M549A1 or future XM1113). ERCA: Extended Range Cannon Artillery. GMLRS-ER: Guided Multiple-Launch Rocket System – Extended-Range. ATACMS: Army Tactical Missile System. PRSM: Precision Strike Missile.

SOURCE: US Army. SLRC and Hypersonic Missile ranges as reported in Army Times.

Murray was referring to a pair of “strategic fires” weapons with thousand-plus-mile ranges: a giant howitzer that uses gunpowder to launch relatively small, affordable missiles, and a high-performance, high-cost hypersonic missile. The Army would like to have both, because they have different strengths and weaknesses to take on different types of targets. But if one weapon doesn’t work, Murray is saying, the service can still wage multi-domain operations with the other.

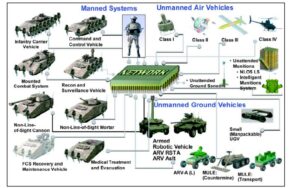

That’s a marked contrast to the Army’s last attempt at wholesale modernization, the Future Combat Systems program, which was cancelled in 2009. FCS was a single mega-contract for everything a future combat brigade would need, from manned ground vehicles to aerial drones and the wireless network to command them.

But the lightweight ground vehicles were too vulnerable to roadside bombs, the drones were too clunky, the network too fragile and cumbersome, and the Army just couldn’t get all the key technologies to work. The problem, Murray said, is “you build a program counting on a technology to mature along a specific timeline, and that technology does not mature.

“Our track record at new development has been absolutely horrendous,” Murray said bluntly. By contrast, he said, the Army has made tremendous improvements to Cold War weapons like the M1 Abrams tank and the M2 Bradley troop carrier, one upgrade at a time.

Now those legacy systems, especially the Bradley, are reaching the point where they lack the space, weight capacity, and above all electric power to accommodate further upgrades, which requires the Army to build something new — but, Murray argued, there is a way to achieve revolutionary change through evolutionary, incremental steps. Instead of going for a great leap forward like FCS, you build what you can with existing technology but leave plenty of room and power to upgrade as new technologies become available. That way you’re neither counting on new tech nor ruling it out. You can take risks on individual technologies because no individual technology is essential to the success of the whole modernization effort.

Army Undersecretary Ryan McCarthy and Gen. John Murray testify on Army Futures Command to the House Armed Services readiness subcommittee

What Has To Change

Modernization will require not only new, streamlined regulations but a new mindset, Gen. Murray acknowledged. “The cultural piece of this is probably going to be the hardest part and culture’s not going to change quickly,” he said. That doesn’t mean changing the Army’s basic principles– “there is absolutely nothing wrong with the seven Army values [like] ‘never leave a fallen comrade'” — but “what I do think we’re going to have to change is a culture of risk aversion.”

There’s at least one big piece of the problem the Army can fix on its own: requirements. These are the official wishlists of what a proposed weapons system should be able to do, often expressed in minutely detailed military specifications.

Sikorsky’s S-97 Raider, a leading candidate for the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft, shows off its agility.

One of the achievements Army leaders like Murray now cite frequently and proudly is how they’ve sped up that process. Take the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft, a high-speed scout. It has gone from a vague concept to preliminary design contracts in 13 months.

The secret isn’t just moving faster, Murray said, but knowing when to stop. In the past, different factions of the Army bureaucracy could spend years and years debating, revising, and adding to a requirements document before finally coming to consensus. Worse, that compromise among the Army’s internal tribes might not reflect what industry could actually build under any realistic budget.

In the new Army Futures Command structure, while Murray doesn’t control the acquisition programs — by law, that falls to a civilian official, Assistant Secretary Bruce Jette — the program managers now sit on Cross Functional Teams with the requirements writers, scientists, and engineers, and give them input from the start. The directors of those CFTs, in turn, report regularly to the Army secretary and chief of staff, Murray said, “and the secretary and the chief personally approve any change in requirements,” rather than letting junior officials go back and forth for years.

It’s worth noting there’s a delicate balancing act here. The Army’s senior leaders need to be involved enough to quash bureaucratic bickering and push for progress, without getting so involved they start micromanaging or punishing subordinates for the inevitable failures.

The Army is still working to streamline its requirements process, Murray told reporters after his talk, with the goal of creating “a quick-fire channel” for high-priority projects. But, I asked him, are you also trying to fix the notoriously labyrinthine joint requirements process run by the Joint Staff and the Office of the Secretary of Defense (JCIDS), which often impinges on service programs? “No,” he said. “I’m going to fix what I can fix first… Where we bump into problems outside the Army, we’ll have to obviously address those; that’s not the initial focus.”

LRPF: Long-Range Precision Fires. NGCV: Next-Generation Combat Vehicle. FVL: Future Vertical Lift. AMD: Air & Missile Defense. SL: Soldier Lethality. SOURCE: US Army. (Click to expand)

That said, the Army isn’t focusing solely on its internal processes. The service has to communicate better with industry — especially innovative firms outside the traditional defense sector — and with Congress, Murray said.

“What I’ve got to do is build on the Army’s culture and understand how to build bridges to cultures that aren’t like the Army – not trying to change them, not trying to change the Army culture, but understand[ing] how to communicate,” Murray said.

That doesn’t include allies yet, Murray said. With his Austin headquarters still less than half-staffed, he’s so far fended off requests from “15 to 20 countries” to send liaison officers. The first foreign liaison at Army Futures Command HQ will be a British officer arriving this fall, he said.

One key audience the Army is reaching out to already is Congress. The Hill is currently wrestling with the radical changes in the Army’s 2020 budget request. “All Congress asks of us is transparency, that they know what we’re trying to do [and we] don’t surprise them with changes,” Murray said. “The Army doesn’t have the best track record for that. As a matter of fact, it’s got a really bad track record for that.”

Today, however, “we are doing a better job of trying to make sure the committees in particular are tracking,” Murray argued. If you sum up all the time representatives from one modernization team or another spend on the Hill, he said, “it’s normally between… 60 and 70 hours a week.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.