Can Army Futures Command Overcome Decades Of Dysfunction?

Posted on

The head of Army Futures Command, Gen. John “Mike” Murray (left), and Army Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley (right), formally unfolded the new command’s colors in Austin.

ARMY S&T CONFERENCE: How broken is the procurement system the new Army Futures Command was created to fix? It’s not just the billions wasted on cancelled weapons programs. It’s also the months wasted because, until now, there has not been one commander who can crack feuding bureaucrats’ heads together and make them stop bickering over, literally, inches.

“I have not always been an Army Futures Command fan,” retired Lt. Gen. Tom Spoehr told the National Defense Industrial Association conference here. But as he thought about his own decades in Army acquisition, he’s come around.

How bad could things get? When he was working in the Army resourcing office (staff section G-8), Spoehr recalled, the Army signals school at Fort Gordon wanted a new radio test kit that could fit in a six-inch cargo pocket. The radio procurement program manager, part of an entirely separate organization, reported back there was nothing on the market under eight inches. The requirements office insisted on six inches, the acquisition office insisted they had no money to develop something smaller than the existing eight-inchers, and memos shot back and forth for months. At last, Spoehr warned both sides that if they didn’t come to some agreement, he’d kill the funding. Suddenly Fort Gordon rewrote the requirement from “fit in a cargo pocket” to “cargo pouch” and the procurement people could go buy an eight-inch kit.

That kind of disconnected dithering is what Army Futures Command is intended to prevent. “I had the money, but nobody really had control of all of this,” Spoehr said. As a result, he said, “we probably spent six months trading memos back and forth on the size of the radio frequency test kit.”

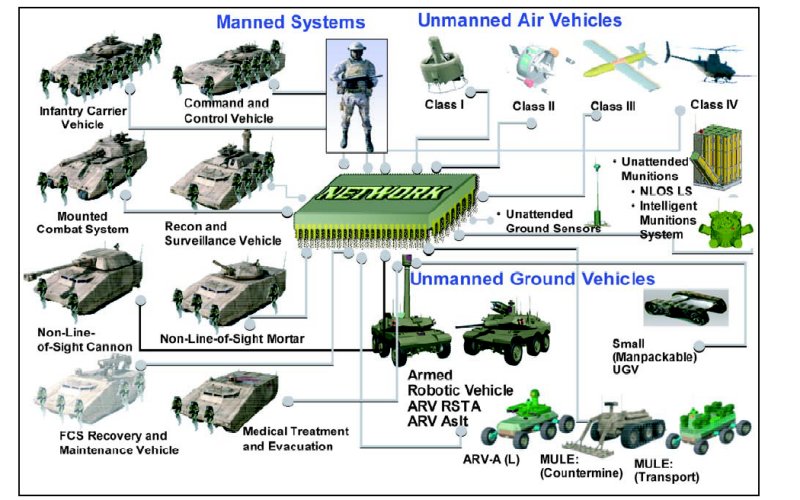

Multiplying that by thousands of requirements over hundreds of systems, and the wasted time and money gets pretty bad. But what’s often worse is when the requirements are unrealistic and no one pushes back. Most notoriously ,Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki demanded easily airlifted Future Combat Systems vehicles that weighed less than 20 tons but had the combat power of a 60-ton M1 Abrams tank. The designs eventually grew to 26 tons, and the performance requirements came down, but by then FCS had lost the confidence of both Congress and Defense Secretary Bob Gates, who canceled it in 2009. It was another casualty of overly ambitious requirements drawn up by staff officers in isolation from the people who’d actually have to build them. Army Futures Command is structured to force those two groups to talk to each other from the start.

“I Was Part Of The Problem”

Admittedly, Future Combat Systems and other cancelled programs were victims of Pentagon-wide budget cuts as well as uniquely Army dysfunctions, Spoehr emphasized. The service has also had successes, he said, especially in fielding urgently needed equipment to Afghanistan and Iraq.

So after a career struggling to make the current system work, “when I first heard about Army Futures Command, perhaps like you, I was like, ‘there’s nothing wrong with the system, we just need to push harder and do better,'” Spoehr admitted with a Freudian slip, “because I have been a prisoner — a participant in Army modernization for as long as I can remember.”

There’s plenty in Spoehr’s career to be proud of, but, he said frankly, “looking back, I can see points in time where I was part of the problem.”

Sometimes it takes a fresher perspective. Spoehr once accompanied a senior official on what’s become the ritual Pentagon pilgrimage to Silicon Valley. During one meeting at Google, Spoehr lamented how much worse the Army was at innovating. Everyone in the room agreed — except for one ex-Army captain who’d joined Google after multiple combat tours. In his experience, the former officer said, Army soldiers on the front line innovated constantly, trying out new tactics and new technologies, particularly to counter roadside bombs. In his experience, the young veteran told Spoehr, it was Google that was less innovative than the Army.

“There are ways to be innovative in the Army,” Spoehr summed up. But you have to protect the innovators from the institutional culture. You can isolate them organizationally, he said, like the Rapid Equipping Force at Fort Belvoir, just half an hour from the Pentagon but independent of the bureaucracy. Or you can isolate them physically, he said, by sheer distance. That doesn’t require deploying them to Afghanistan or Iraq to innovate under fire, like the young captain, he said: “You can send them some place else like Austin.”

Austin, of course, is where Army Futures Command officially stood up its headquarters just last Friday.

“Totally Focused On The Future”

Futures Command is the Army’s biggest reorganization in 40 years. One key component of it is brand-new: the eight Cross Functional Teams created last fall. Each CFT pull together experts in technology, requirements, and acquisition from disparate bureaucracies and put them in one room under one combat-hardened commander to solve a particular high-profile problem, like long-range missiles or armored vehicles.

Gen. John Murray, first chief of Army Futures Command, speaks at its formal activation Friday in Austin.

But much of Army Futures Command is just a new leader for existing organizations to report to. The new commander in Austin, Gen. John “Mike” Murray, will take over the Army’s in-house research, development, and engineering labs (RDECOM) from Army Materiel Command (AMC), whose main focus is maintaining and sustaining current equipment. Murray will also take over the service’s in-house think-tank on future warfare, the Army Capabilities Integration Center (ARCIC), from Training & Doctrine Command (TRADOC), whose main focus is training and educating the current force. The idea is to extract the future-focused fragments of the Army from organizations preoccupied with day-to-day demands and instead put them under a commander whose only mission is to think about the long term.

“It’s the first organization that is totally focused on the future,” the Army’s Vice-Chief of Staff, Gen. James McConville, said of Army Futures Command. “For the last 16, 17 years we’ve been focused on combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and we’ve been focused on the present. When you focus on the present you tend to incrementally improve the force…not getting those leap-ahead technologies that we know we need.”

“We’re going to have operators, technologists, and acquisition professionals working together,” McConville told the NDIA conference. “We’re seeing this happen very quickly already with our Cross Functional Teams.”

That said, while RDECOM and ARCIC will report to Army Futures Command, their people aren’t physically moving to Austin, which would be expensive and uproot them from existing infrastructure. Even so, the change will be disruptive at first, warned the Army’s civilian acquisition chief, Bruce Jette.

“The benefit is… now really we’ve an organization focused on the future,” Jette told the NDIA conference. “The difficulty is that it takes so much to put together an organization in place that you kind of stall (other efforts).” It’ll take “six or 12 months” to work out how the Army labs will need to change, he estimated.

But change is necessary, Jette said: “There are great people in the lab system, there are great facilities in the labs, (but) how we use them sometimes doesn’t capitalize on those capabilities.”

The same is true at Training & Doctrine Command. With soldiers dying to guerrillas and terrorists since 9/11, TRADOC has gotten pretty good at training for irregular warfare in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. But it had largely neglected great-power conflict, which roared back onto the agenda after Russia invaded Crimea in 2014.

The Army’s M1 Abrams tank and other mainstay weapons systems were developed in the 1970s and fielded in the 1980s, during the last great period of reform.

Back To The Future?

The last time the Army had to shift gears and play catch-up on this scale was in 1973, the year the US military both pulled out of Vietnam and saw Israelis using US equipment get badly mauled by Soviet-armed Arabs. The reorganization that followed created the current ruling trinity of Training & Doctrine Command, Army Materiel Command, and Army Forces Command. That troika laid the technological and intellectual foundation for revival in the 1970s, then built a new and better army with Reagan buildup funds.

But after 1986, recalled retired Maj. Gen. Bill Hix, the structure began to fall apart. The Soviet threat lost its urgency before fading away entirely, and the big three commands began to lose their close connections to each other and to Army headquarters in the Pentagon. “(With) the atomization of that community, that singularity of purpose, we wound up with individual organizations that were variously connected to each other,” he told the NDIA conference. “Authorities and responsibilities became increasingly ambiguous over time.”

Strong leaders who worked well together could still bridge the gaps and get things done, but that happened in spite of the system, as “an accident of personality,” Hix said. “In the absence of that accident, we have bled money and chased after shiny objects.”

“The fundamental idea of AFC is to regain that vertical and horizontal integration” that we had in the 1970s after the last big reform, Hix said.

Success will require continued focus from the top. The Army’s current crew of senior leaders — Secretary Mark Esper, Undersecretary Ryan McCarthy, Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley, Vice-Chief McConville, and senior acquisition executive Jette — are working closely together and paying “unprecedented” attention to fixing acquisition, Spoehr said. That includes not only creating Army Futures Command and the Cross Functional Teams, he said, but also reviving the Army Requirements Oversight Council, which now actually holds frequent high-level meetings on key programs rather than just passing memos back and forth.

But new leaders will take over long before today’s reforms bear fruit by delivering new weapons to frontline units. “That level of interest has to be maintained,” Spoehr said. “Otherwise this train could very easily go off the track.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.