Will THAAD Deployment Roil Or Calm Troubled Pacific?

Posted on

US Army THAAD missile defense vehicle unloading in South Korea.

WASHINGTON: The deployment of improved US missile defenses to Korea, THAAD, comes at a time of growing disorder across the region.

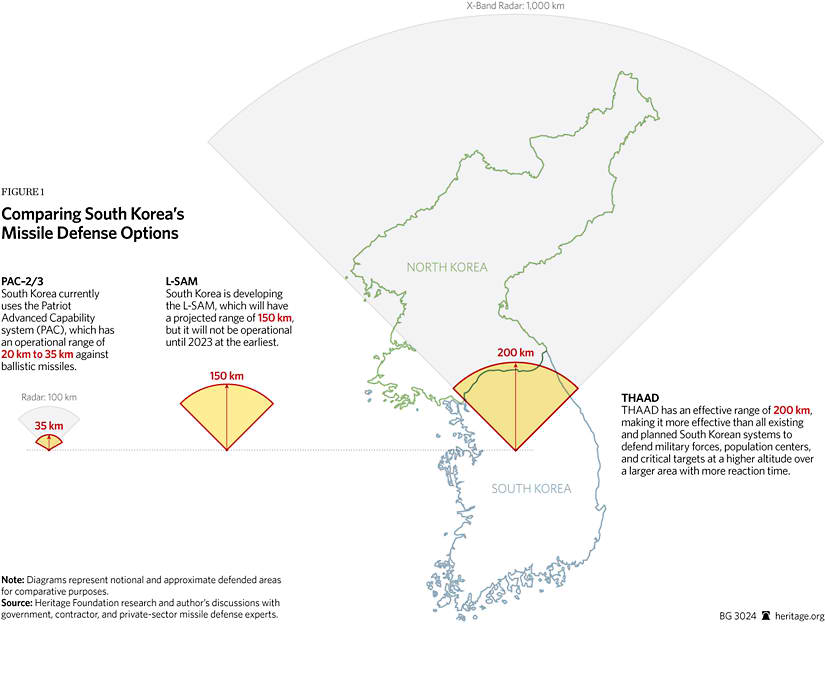

There is one constant in this equation but three major unknowns. The constant is the THAAD system itself, whose capabilities — almost six times the maximum range of current Patriot missile defenses and roughly five times the maximum altitude — will definitely improve the defenses of South Korea against missile attack. The variables are:

- South Korea has impeached its right-wing president. The leading candidate to replace her is a dove who’s questioned the THAAD deployment and urged outreach to North Korea. Will Seoul go wobbly?

- China has aggressively rattled sabers in the East and South China Seas — including deploying missile defenses on disputed islets — but often with counterproductive results, driving alarmed neighbors towards the US. Will Beijing relent?

- North Korea has gone beyond engaging in internationally condemned missile launches and nuclear tests into James Bond villainy, recruiting young women to kill its boy dictator’s exiled half-brother with nerve gas. Is Pyongyang going nuts?

THAAD missile defense coverage (200 km range) compared to Patriot (35 km) and South Korea’s in-development L-SAM (150 km). Credit: Heritage Foundation

Setting A Precedent

It’s important to remember the context, that the THAAD deployment is a response to a long pattern of provocation, not a provocation in itself, argues Heritage Foundation scholar Bruce Klingner.

Bruce Klingner

“THAAD increases defense against a country which has repeatedly violated UN resolutions, conducted deadly attacks, threatened nuclear annihilation against the US and its allies, declared it will never abandon its nuclear weapons, and declared the Six Party Talks and the armistice and null and void,” Klingner says. “To argue that THAAD is destabilizing is like blaming the policeman who dons a Kevlar vest as being the cause of rising crime.”

“This is a very well-orchestrated move by the U.S.-ROK (Republic of Korea) alliance,” said Zack Cooper, an Asia scholar at the Center for Strategic & International Studies. While the deployment has been in the works since last summer, Defense Secretary Jim Mattis pushed to accelerate it on his recent trip to Korea — his first as SecDef. Then the THAAD launchers landed one day after a salvo of North Korean missile tests which Pyongyang itself described as practice for a preemptive strike. Deploying a THAAD system requires extensive preparation and the US was clearly ready to go at a moment’s notice.

Zack Cooper

“I wouldn’t be surprised if the two governments had been planning to deploy THAAD, but wanted to wait for a North Korean provocation before doing so,” Cooper told me. “By rapidly deploying THAAD in response to a North Korean provocation, the alliance has shown that it can quickly strengthen its defensive capabilities when needed, but also done so in a way that make it more difficult for opponents of THAAD to paint the deployment as an escalation.”

“Moreover,” Cooper continued, “South Korea’s decision to move forward demonstrates that China’s neighbors can stand up to economic pressure from Beijing” — China has practiced economic warfare against South Korean companies to stop Seoul from accepting THAAD — “which will be critical in the years ahead.”

Tom Karako

“A single THAAD battery does not represent the end of missile defense deployments on the peninsula, nor is it the beginning, but it may represent the end of the beginning,” said CSIS missile defense director Tom Karako, channeling Churchill. “Much more will be needed, but this important step signals…to both the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) and to China that the United States and its allies are serious about the threat from the North, and will not tolerate vetoes from China or anybody else.”

In other words, all three scholars argue that — whatever short-term turmoil may arise — in the long run standing up to China, standing up to North Korea and strengthening South Korean defenses will make international bullying less likely. The first crucial question is whether South Korea agrees.

A Utah National Guard artilleryman during an exercise in Korea.

South Korea: A House Divided

South Korea’s turbulent politics make America’s 2016 election look tame. The country’s ambivalence about deploying THAAD is just one manifestation of generational divides about how to deal with North Korea, the United States, and China. It is also deeply divided on domestic issues, with military dictatorship in living memory and current president Park Guen-hye the daughter of a general turned president-for-life: Both he and Park’s mother were assassinated. Park is now under impeachment and the leading candidate to replace her is the dovish Moon Jae-in.

Moon Jae-in

Moon was close to Park’s predecessor, Roh Moo-hyun, who advocated a “Sunshine Policy” of closer ties between North and South. (Roh was brought down by a corruption scandal, like Park, and committed suicide). Moon has called for a rapprochement with North Korea, criticized military intelligence-sharing arrangements with Japan, and questioned the THAAD deployment, said retired Rear Adm. Michael McDevitt at an Atlantic Council event yesterday.

So would a President Moon send THAAD back to the US? Probably not. “A new ROK leader could certainly reverse decisions made by the previous administration, but I think that continuing belligerence from North Korea or pressure from China would make such reversals more difficult,” Cooper told me.

“The THAAD deployment will likely be complete by the time the next South Korean administration takes office,” said Klingner. “As such, it is unlikely to be undone… If Moon were to become president and request THAAD’s removal, that would cause strains within the alliance and would be a signal of a rocky relationship with Washington during his tenure.”

That said, a Trump-Moon relationship could be plenty rocky even if THAAD stays in place. Some of Moon’s proposals for outreach to North Korea arguably violate UN sanctions. What’s more, since THAAD is hardly the be-all, end-all to missile defense, there are many improvements that Moon could block — especially an expansion of the hard-won but grudging Korean cooperation with Japan, which is particularly badly needed in missile defense.

Chinese weapons ranges (CSBA graphic)

China: Know When To Fold ‘Em?

After a generation of international charm offensives, China has shifted to a much more assertive, even aggressive approach. Beijing’s has publicly denounced THAAD and used economic pressure tactics to dissuade Seoul from the deployment. Those attempts at arm-twisting failed to deter the Koreans from deploying THAAD and, at worst, strengthened their resolve to defy China.

It’s a common pattern for China, trying to bully neighbors (assert PRC rights) and neighbors say no. When China unilaterally claimed jurisdiction over a vast Air Defense Identification Zone in the East China Sea in 2013, it included not only islands both the China and Japan claimed, but also territory claimed by South Korea. Not only did China irritate two important neighbors, almost every nation has ignored China’s ADIZ.

The “9-dash line” describing Chinese claims to the South China Sea

Further south, China’s Nine Dash Line claim to most of the South China Sea, and its building and fortifying artificial islets in waters to which the international community says it has no right, has created friction with almost every country in Southeast Asia. (Ironically, despite its denunciation of THAAD in South Korea, China is placing its own missile defense batteries on disputed islands). Even the one nation without a directly conflicting claim, Indonesia — the region’s giant — has departed from its normal scrupulous neutrality to forcefully escorted Chinese fishing vessels out of its Exclusive Economic Zone around the Natuna Islands, and has conducted major military exercises around the islands.

Beijing has demonstrated some ability to back off. While its quasi-civilian Coast Guard continues to patrol Japanese-claimed waters around the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands, for example, it lifted its embargo on selling rare earth minerals to Japan, said Klingner. But China is now embargoing South Korea on everything from rare earths to kimchee, he said, but history suggests they’ll ease these too, eventually.

What’s the worst China could do? Besides further sanctions, it could conduct weapons tests or military exercises to try and demonstrate that THAAD won’t stop its missiles. That’s easily done, since a THAAD battery oriented to defend South Korea against the North could be outflanked by a strike from Chinese territory to the west, while Chinese ICBMs aimed at the US would never fly anywhere near THAAD’s coverage zone. China could even demonstrate its ability to take out the THAAD sites or overwhelm them with sheer numbers of missiles.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi

So far, however, China has been — for China — conciliatory. Foreign Minister Wang Yi today urged restraint on both sides and suggested North Korea should cease nuclear tests in exchange for the US and South Korea suspend large-scale military exercises. This is actually recycling an old North Korean proposal that conveniently ignores the North’s nuclear program violates six different UN Security Council resolutions, all of which China either supported or at least abstained on. But at least it’s more nuanced than denouncing the US. More substantively, China has taken steps to comply with a UN embargo of North Korean coal exports, a crucial source of income for Pyongyang.

“The Chinese will no doubt criticize THAAD and might put on additional economic pressure to try to reverse the decision,” Cooper told me, “(but) alternatively, Beijing might recognize that the deployment has already occurred and therefore relieve some of the economic pressure to prevent damaging relations with Seoul….If I were a Chinese leader, I’d probably do the latter, but the Chinese may want to send a message to other states that disregarding their warnings will come at a cost.”

If they do ratchet up pressure on South Korea, though, it will be doubling down on a strategy that’s mostly backfired so far. Ultimately, Cooper said, “If China and others want to stop the THAAD deployment, then they need to address the core reason for the deployment by taking steps to prevent North Korea’s missile and nuclear programs from progressing.”

North Korea’s young leader, Kim Jong-un.

North Korea: The Wild Card

While China’s behavior may be somewhat predictable, North Korea’s is not. McDevitt argues that Kim Jong-un’s most dramatic recent outrage, the assassination of his half-brother in Malaysia, was intended to ensure that Beijing has no alternative to his rule.

“Kim Jong-un is carefully eliminating all the potential…. candidates that China could use to replace him,” McDevitt said at the Atlantic Council yesterday. “He just took care of his half-brother. He took care of his uncle a couple of years ago, and slowly but surely, anybody in North Korea who has the potential to be somebody China would (back), those are being eliminated….Those cards are being removed from China’s hand.”

However politically logical it was to murder his half-brother, however, how Kim choose to kill him suggests a disturbing lack of judgment and a dangerous flair for drama. (His late father, Kim Jong-il, was obsessed with movies, including James Bond). Having already executed at least five domestic opponents with anti-aircraft cannon, Kim apparently couldn’t just order an agent to slip poison into someone’s drink or quietly cut the brake lines on their car.

Kim Jong-nam, assassinated half-brother of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un.

Instead Kim apparently recruited two young women to smear liquid nerve gas on the target not just in public, but in a crowded airport under constant video surveillance. Both women — one Indonesian, the other Vietnamese — were swiftly and unsurprisingly captured by Malaysian authorities, while North Korean suspects holed up in the embassy. North Korea tried to shut down the investigation by holding 11 Malaysians hostage, which has only got Malaysia’s back up more. Kim may have eliminated a rival and reduced China’s options for replacing him, but he did so at the cost of his relationship with one of the only countries that was willing to have diplomatic relations and trade with North Korea.

Is Kim Jong-un, the head of a nuclear state, acting rationally? So far he has avoided the worst international excesses of his forebears. His father, Kim Jong-il, North Korea sank a South Korean naval vessel, the Cheonan, killing 46, and dispatched infiltrators to the South in mini-submarines. His grandfather, Kim, ordered Northern agents to blow up a South Korean airliner, killing 115 — after invading the South in 1950, leading to the deaths of five million people. But he holds nuclear weapons and is willing to kill people in full view of the world using a banned nerve agent. Is that rational?

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.