Why We Lost The Afghan War

Posted on

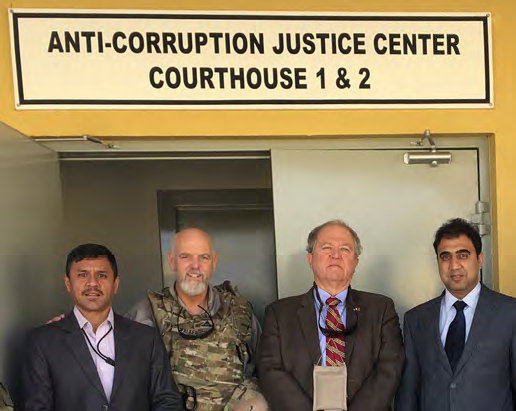

CID special agents return from corruption raid at Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan

U.S-enabled corruption lost the Afghan War. The Afghan government is a failed state, incapable of effectively governing or defending its citizens. Corruption funds the enemy, with hundreds of millions of dollars skimmed from U.S. logistics and aid money. Former Ambassador to Afghanistan Ryan Crocker said in 2016: “The ultimate point of failure for our efforts … wasn’t an insurgency. It was the weight of endemic corruption.”

U.S. officials knew corruption was a serious threat and established several anti-corruption units in 2009 and 2010. The National Security Council mandated the multi-agency Afghan Threat Finance Cell (ATFC) to disrupt politically connected networks financing the insurgency. The U.S. military’s Task Force 2010 focused on the enormous sums the insurgents extorted from military logistics contractors and poorly managed “nation-building” development projects. Task Force Spotlight scrutinized insurgent-connected Afghan private security firms. Amb. Karl Eikenberry and then-Gen. David Petraeus jointly established the civilian-military Rule of Law and Law Enforcement (ROL/LE) structure to reform Afghanistan’s graft-ridden police, judiciary and penitentiary system.

Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction meets with Afghan prosecutors and judges

Established by then-Adm. Mike Mullin and Gen. David Petraeus as part of the counterinsurgency strategy, CJIATF-Shafafiyat (Transparency) was the military’s leading anti-corruption task force. Initially commanded by then-Brig. Gen. H. R. McMasters, now President Trump’s national security advisor, Shafafiyat investigated the opium-and-corruption networks that connected Afghan powerbrokers with the Taliban.

That was over six years ago, when U.S. troop levels were soaring toward the 100,000 mark. Counterinsurgency, with its ambitious nation-building component, was the richly funded strategy of the moment. But even with Obama’s surge of troops and money, the U.S. anti-corruption teams were attacking a massive problem with modest resources. And the anti-corruption campaign was subject to intense political pressures—both Afghan and American. So what happened to the U.S. anti-corruption initiative?

“We made a Faustian bargain,” says Special Inspector for Afghanistan Reconstruction John Sopko about the devolution of U.S. counter-corruption efforts. The political calculus began in 2009, when U.S. investigations began to uncover malfeasance connected to powerful government insiders. Increasingly prickly, Afghan President Hamid Karzai lashed out at U.S. officials, blaming the international community for the corruption.

The conflict came to a head in July 2010 when U.S.-mentored Afghan special police arrested Muhammad Zia Salehi, a minor official in the Karzai administration, charging him with influence peddling. After Karzai intervened, Salehi was released. Embassy officials stated the president needed to “save face.” (The real reason was made clear in 2013 when a New York Times story about the CIA delivering bags of cash to Karzai revealed that Salehi was his bagman.)

In 2011, Karzai again forced the U.S. to back down, this time regarding the financial crimes committed by highly connected Kabul Bank officers, who stole almost a billion dollars. “He’d yell and stomp his feet, and everybody would run away,” ATFC founding director Kirk Meyer says of Karzai’s reactions.

Sarah Chayes, corruption expert and author of Thieves of State, witnessed the dramatic shifts in the U.S. anti-corruption policies in Afghanistan—shifts that began in Washington. “The political climate was anti-war,” Chayes told me. “Obama wanted to keep the war off the front pages, which made them shy away from the corruption issue.” Chayes says Petreaus’s anti-corruption support also rapidly waned: “Petraeus saw Washington wasn’t going to back him up on this as part of the campaign. He was a consummate politician. Once he saw the USG in Washington dropped corruption, Petraeus pivoted to killing people.”

With counterterrorism the de facto doctrine, U.S. leadership decided they needed Karzai’s support at any cost. Counterinsurgency quickly became a dirty word. Counter-corruption was outré. Often squabbling anti-corruption units struggled to make progress. Expediency ruled decision-making in what staffers called “politically charged meetings.”

Chayes points to an early 2011 classified Obama administration memo, Objective 2015, which essentially barred the Department of Justice from mentoring Afghan anti-corruption prosecutors. Chayes says the “writing between the lines” tacitly declared, “We are not going to address corruption.”

Cutting U.S. counter-corruption mentoring had multiple impacts. Not only did the U.S. decision stop the training of neophyte Afghan anti-corruption officials, it also removed crucial oversight in graft-ridden ministries. Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction (SIGAR) John Sopko says, “It’s obvious, if you don’t have capacity, you can’t mentor Afghans on corruption. Mentoring is not just training, it also provides ‘top cover’ for the honest officials, who can blame the U.S. mentor. Without mentoring, the honest Afghans are overwhelmed by peer pressure.”

The State Department and military emphasized working with the Afghan government officials, no matter how crooked. Tim Jones, who was the Afghan Threat Finance Cell director from 2011 to 2014, told me U.S. embassy officials were often opposed to anti-corruption investigations. “They wanted to distance themselves away from that. They wanted to play nice. It was a protection thing with them. They’d say about investigations into corrupt actors, ‘No, that would be too political. This is the devil we know,’” says Jones. “The U.S. government didn’t have the stomach to do these kind of investigations. Karzai was not our friend. It was a tragedy what was going on.”

Though corruption in Afghanistan continued unabated as the U.S. withdrew troops, the anti-corruption teams were “bleeding personnel,” as ATFC staffer Frank Calestino says. The military reduced billets in the anti-corruption units. The State Department began slashing personnel in the anti-corruption teams. The FBI left in 2011; the DEA reduced its staffing, as did Homeland Security Investigation (HSI). “State Department wanted to ‘right-size’ the embassy,” Sopko says. “Afghanistan is never going to be ‘right.’ It’s not Norway; it’s not Switzerland. ‘Right-sizing’ was bogus.”

The Faustian bargain compromised the State Department’s ROL/LE structure. Fearing an irate reaction from Karzai, diplomats would still occasionally threaten reduced assistance and support, but Karzai called their bluff time and again. Ambassador Stephen McFarland took over as the Coordinating Director of ROL/LE in January 2012, after postings to insurgent hot spots such as El Salvador, Guatemala and Peru. “I never felt like the embassy said corruption was off-limits,” McFarland says. “But there was no political tool—such as reducing support—to make it better. The corruption situation just kept getting worse.”

Citing the success of unstinting congressional pressure for human rights during the El Salvador civil war, McFarland says conditionality helped bring reform to that conflict. “We should have called Karzai’s bluff,” McFarland says. “The Afghans called our bluff. We didn’t call theirs.” ROL/LE ended in July 2013.

Through the troop drawdown, the surviving anti-corruption teams tried to continue their missions—sometimes in competition with one another. “As the BOG (boots on the ground) hit us, we set a satellite office in Qatar,” Jones says, “but TF 2010 saw it and took our space.” By the time Jones left in January 2014, the ATFC was gutted—“functional in name only,” Jones says. By late 2014, ATFC was gone.

The military’s anti-corruption units closed down prior to Operation Enduring Freedom’s end on December 31, 2014. TF 2010 lasted longer than most by morphing into base-security vetting. TF Shafafiyat ended in the fall of 2014. “Our systems, our process, our policies just didn’t work. There was governance in one bucket; security in another bucket. It wasn’t a capacity issue,” one TF Shafafiyat staffer says. “It was a will issue—both the Afghan side, and the U.S. side. There was no political will. There was a culture of impunity. If you’re connected, you’re good. It created pools of discontent that the Taliban exploited.”

Where are we today? It’s clear that corruption undermined popular support for the Afghan government, and exacerbated insecurity. Sixteen years into the American intervention, Afghanistan’s government is ranked among the world’s most corrupt; ninth on the Fragile States Index.

Despite $117 billion of U.S. development aid since 2002, Afghans remain near the bottom of most human development indices—victims of “phantom aid,” development funding wasted through pernicious greed in both donor and recipient countries.

The National Unity Government of President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah took office in 2014 promising to address corruption. After a few highly publicized arrests, there is little to show. A UN corruption report states, there is “a lack of political will.” When asked about U.S. counter-corruption efforts in Afghanistan, both the State Department and military defer to the Afghan government. SIGAR John Sopko says, “Ghani and Abdullah are both honest, but they’re up against a tough nut. They are relying on the corrupt people to clean out corruption. With the capacities gone, security is going to hell in a handcart.”

Empowered and financed by this corruption, Taliban strength has grown at double-digit rates annually since 2005. Insurgents now control about 40 percent of the countryside, and are pressuring government centers across country, including increasingly besieged Kabul.

The latest report to Congress from the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction summarizes the state of conflict:

- Conflict-related civilian casualties in Afghanistan rose to 11,418 in 2016 – the highest total civilian casualties recorded since UNAMA began documenting them in 2009.

- Security incidents throughout 2016 and continuing into the first quarter of 2017 reached their highest level since UN reporting began in 2007.

- 660,639 people in Afghanistan fled their homes due to conflict in 2016 – the highest number of displacements on record and a 40% increase over the previous year.

Insurgencies are centripetal, moving from the countryside into the government centers. The Special Forces’ dictum has long been that if an insurgency isn’t shrinking, it’s succeeding. The Taliban don’t need to come to the negotiating table. Thanks in part to the failed counter-corruption campaign, the insurgents are winning.

Douglas Wissing, a journalist who has contributed to The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post and other outlets, is the author of Hopeless but Optimistic: Journeying through America’s Endless War in Afghanistan and Funding the Enemy: How U.S. Taxpayers Bankroll the Taliban.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.