Why I Wrote The Book About Predator

Posted on

Rick Whittle wrote the book on the V-22, which he covered for several thousand years while a Washington reporter for the Dallas Morning News. Now he’s written the book on the Predator (on sale Monday), the drone (no RPAs on this site) and he’s obtained a great deal of operational information about Predator and the battle against Al Qaeda, much of it never before reported. Let Rick tell his story. The Editor.

Rick Whittle wrote the book on the V-22, which he covered for several thousand years while a Washington reporter for the Dallas Morning News. Now he’s written the book on the Predator (on sale Monday), the drone (no RPAs on this site) and he’s obtained a great deal of operational information about Predator and the battle against Al Qaeda, much of it never before reported. Let Rick tell his story. The Editor.

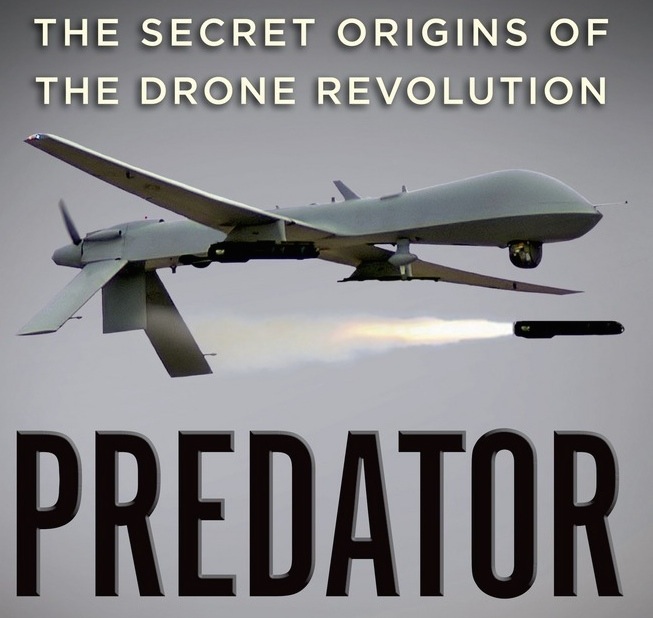

The editor of Breaking Defense knows how to ask the tough questions, but Colin Clark threw me a softball when he asked me to explain to his audience how my new book, Predator: The Secret Origins of the Drone Revolution, came about.

Five years ago, just after I’d finished writing a book about the V-22 Osprey, my literary agent asked what book I might write next. “I’m not sure,” I told him, “but these unmanned aerial vehicles look interesting.”

“These what?” he said.

“Drones,” I said, using a word many experts dislike but one that my agent immediately grasped. (As I’ve written before on this site, “drone” is now a generic term for unmanned aircraft of any type, and like it or not, it’s here to stay.)

At first, I had in mind to write a comprehensive book about UAVs. But then I read a July 2008 article in Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine describing 10 “Aircraft That Changed the World.” One of the 10 — and the only UAV — was the Predator. That brought things into focus for me. The story of the drone that changed the world was one I knew I wanted to write. The saga of the Predator, though, turned out to be not just the story of an extraordinary aircraft, but also a story of invention, a story of war, a story of the Air Force, a story of the CIA, and the story of how a new age in aviation began.

The Predator was the first “endurance UAV,” a drone able to circle over a target area, unseen and unrelenting, for 24 hours or more. The Predator is also the first weapon in history whose operators can fly it by remote control above the other side of the globe and use it – much like a sniper — to stalk and kill a single individual from a position of utter invulnerability.

But as I found out in five years of research and hundreds of interviews, this extraordinary weapon didn’t start out that way, and it wasn’t created by the much-maligned military-industrial complex. The Predator was invented and transformed into a world-changing technology by a cast of characters no novelist could conjure up. They shared their stories with me, in some cases letting me interview them for more hours than a Predator can fly. Most were iconoclasts, resisted at nearly every turn by the very institutions that later fell in love with this new technology.

The dramatis personae begins with Abraham Karem, a genius engineer at Israel Aircraft Industries who quit to build UAVs, emigrated to the United States and then used his Los Angeles garage to design a drone that could stay in the air 10 times longer than any previous unmanned aircraft. Karem went bankrupt trying to sell his concept to the military, but his designs and inventions were saved, and he and his team were hired, by a pair of bold entrepeneur brothers, Neal and Linden Blue, who were also aviators. A couple of years earlier, the Blue brothers had bought a San Diego company they renamed General Atomics and decided their nuclear energy firm should also develop a UAV to help fight the Sandinistas in Nicaragua and deter the Soviets in Europe.

As I say in my book, if necessity is the mother of invention, war is the mother of necessity, and as with many technologies – especially in aviation — war created necessities that made the bargain basement price the Blues paid for Karem’s assets pay off big.

In 1993, CIA Director James Woolsey and Undersecretary of Defense John Deutch broke ranks with many in their agencies by deciding they needed endurance UAVs to find Serb artillery that was bombarding civilians in Bosnia. One result was the Predator, whose first war was Bosnia. A shortage of airborne reconnaissance planes led Gen. Ronald Fogleman, then Air Force chief of staff, to break with his service’s ingrained disinterest in UAVs and wrest control of the Predator away from the Army and Navy. The cast of iconoclasts also includes another fighter pilot, Gen. John P. Jumper, who saw the Predator’s potential as a “hunter-killer scout” and decided to arm it.

I discovered the largely unsung roles in the Predator story played by Fogleman and Jumper after I met a senior Air Force civilian named James G. Clark, a bureaucratic operator who prefers to be called by his nickname, Snake. In another of my early interviews, former Air Force Secretary Whit Peters had pointed out that when the Predator emerged in the mid-1990s as a simple eye-in-the-sky, it was a bit like the first personal computers – a new piece of technology that some people found interesting but most couldn’t see much use for. Over time, however, creative thinkers came up with innovations — new software, new hardware, new communications architectures – that transformed the personal computer into a revolutionary technology. As Peters observed and my book documents, much the same thing happened with the Predator.

Snake Clark helped me see that, in the Predator’s case, much of that transformation was accomplished by a secretive Air Force technology shop called Big Safari, officially the 645th Aeronautical Systems Group – an outfit built on innovation and iconoclasm. With some pivotal contributions from an inventive technoscientist Snake Clark calls “The Man With Two Brains,” and in my book I call by the alias “Werner,” Big Safari transformed the Predator from a novel way to watch a battlefield into a wonder weapon able to strike targets on the other side of the planet. A largely secret war with Al Qaeda that unfolded after Big Safari began modifying the Predator in 1998 led to the Air Force being assigned two years later to fly the unarmed version over Afghanistan to find Osama bin Laden for the CIA.

As my books reveals, that mission was accomplished by an Air Force team using a ground control station at Ramstein Air Base in Germany. The necessity of moving that ground control station so that the trigger on the first armed Predator could be pulled on U.S. rather than German soil gave birth to “remote split operations,” the intercontinental data link the Air Force still uses to fly drones on the other side of the globe. My book takes the reader into the first ground control station used to fly such missions – a faux freight container parked at CIA headquarters – and describes firsthand the first lethal intercontinental drone strike in history, on Oct. 7, 2001. My book describes for the first time in detail how, thanks to command and control confusion, Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar escaped becoming the Predator’s first successful high value target strike. My book details for the first time the role the Predator later played in killing bin Laden’s trusted military commander, Mohammed Atef. My book also reveals how, a few weeks later, the Predator’s cameras, missiles, and endurance helped save American lives during a battle on an Afghan peak known as Roberts Ridge.

When the war in Afghanistan began in the fall of 2001, the U.S. military had two armed drones. (Three armed Predators were deployed after 9/11 but one crashed before the conflict began.) A Pentagon report that year predicted that by 2010, the nation might have 290 UAVs of three types. But arming the Predator changed the way people thought about UAVs. When 2010 rolled around, the U.S. military had nearly 8,000 drones of fourteen types and the CIA was being accused of an addiction to drone strikes against terrorists.

A reporter gets to tell a story like this maybe once in a lifetime.

Our review of “Predator: The Secret Origins of the Drone Revolution,” will run Monday morning, before Rick speaks at 1 p.m. at the the Air Force Association conference.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.