When The Football Comes Out, Who Watches The President?

Posted on

Corrected: The article referred to the E-4B command aircraft, but Brig. Gen. Bowen was referring to the E-6B.

WASHINGTON: The men and women of US Strategic Command watched a clock count down. When it did, they knew their base would be “a smoking hole in the ground.” It was a simulation, sure, but “it’s deadly serious,” said Army Brig. Gen. Gregory Bowen. As STRATCOM’s deputy director of global operations, he commanded the 10-day Global Thunder 2018 exercise when STRATCOM chief Gen. John Hyten had to sleep.

Gregory Bowen takes the oath of office on being promoted to brigadier general.

“At the end of the final exchange of missiles, down in…what we call the battle deck, which the commander operates from (at Offut Air Force Base), there’s a countdown clock to when Omaha is going to become a smoking hole in the ground,” Bowen told the DefenseOne conference here. “When that clock hit zero, they shut down all the screens, and the lights dim, and everybody just sat there for a minute and thought about what just happened.”

The primary purpose of the Global Thunder wargame is to test STRATCOM’s global command, control, and communications network. “We’ve got to operate in a degraded environment,” said Bowen. That means reports and orders may not get through because of computer hacking, electronic jamming, or nuclear weapons physically blowing holes in the network – leaving commanders increasingly in the dark.

As the simulated conflict progresses, Bowen said, “it basically forces us to devolve our command and control all the way down so the last thing remaining is the jet.” That’s a converted Boeing 707 packed with electronics called an E-6B Mercury, better known by the Cold War codename Looking Glass. Even in extremis, Bowen said, “we still have that survivable capability to execute the president’s orders.”

E-6B Mercury nuclear command and control aircraft.

Presidential Power

But what if the president gives bad orders? Speaking on a DefenseOne panel alongside Brig. Gen. Bowen, Joseph Cirincione of the anti-nuclear Ploughshares Fund said that concerns about President Trump’s bellicose rhetoric had drawn attention to a fundamental flaw in our nuclear command and control. It takes two officers turning keys at once to launch one missile, but the president can single-handedly give the order to launch them all. Senator Bob Corker, a seasoned critic of Trump, will hold hearings next week on the president’s nuclear authorities – the first in 40 years.

Joe Cirincione

“Once he gives the order, no one can overrule him. It would require something on the order of a full scale mutiny to stop the president’s order from being executed. Once he gives the command and it’s verified as a legal command, the missiles launch in four or five minutes,” Cirincione said. “Why do you give one person that authority?”

Brig. Gen. Bowen defended the current system. “It is designed the way it is for a reason, and that is to be able to rapidly respond in an in extremis situation (with) missiles inbound,” he said, “but having said that, it is a very tightly scripted process.” The president is put in contact with the secretaries of Defense and State, with the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and other key advisors, Bowen said. The military presents the president with options, which always include doing nothing or responding with conventional forces only, as well as a nuclear counterattack.

That’s great on paper, Circincione countered, but there’s nothing that compels the president to confer with any of these people, let alone to listen to them. Yes, if the president gave an order to stage a nuclear first strike out of the blue, his subordinates might balk and find legal grounds to do so, Cirincione said. But in the heat of a crisis, he argued, they would salute and launch.

Crises have a strong tendency to escalate, Brig. Gen. Bowen agreed. STRATCOM’s wargames teach that if a conventional conflict breaks out with a nuclear power – say, Russia – the nukes are likely to fly sooner or later. In fact, that was the scenario in Global Thunder. “It takes you from one end to the other,” Bowen said. “It begins with a conventional conflict, things start to go bad, there’s a nuclear exchange.”

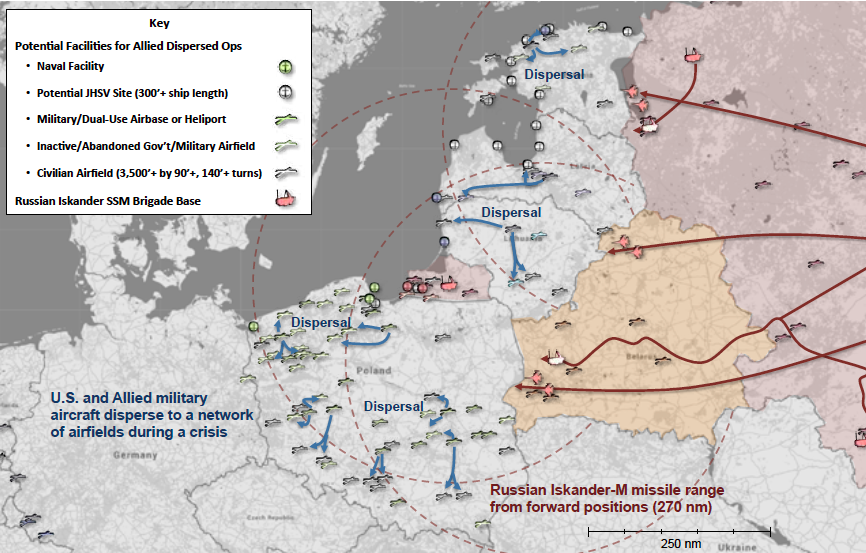

Defense of the Baltic States and Poland against a notional Russian missile barrage. (CSBA graphic)

Can you stop that escalation? “It’s dicey, it’s dicey,” Bowen said. “When one side begins to lose, then (there’s) the temptation to utilize those weapons.”

It’s especially dicey when one side has a declared doctrine of “escalate to deescalate.” Russian officials have said that if they’re losing a conventional conflict, they may conduct a limited nuclear first strike to force their opponent to back down. Their terminology is classic Russian misdirection, as Bowen noted: “The Russians escalate to win, not to ‘deescalate.'”

A B-52 test-fires an unarmed Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM).

Cirincione argued that some US thinkers share the Russians’ fixation with a limited first strike, and their delusion that the consequences could be contained and escalation controlled. It’s this mindset, he said, that leads to calls for more “usable” nuclear weapons, such as the controversial replacement for the aging Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM).

Bowen disagreed. He argued the ALCM is just one of a host of systems we can no longer put off modernizing, like the B-52 bomber, the Ohio-class submarine, and the nuclear command-and-control network itself.

“We’ve painted ourselves into a corner. We’ve deferred these decisions over the years (and) all of the systems are getting old,” Bowen said. “All of this stuff is getting old, and we need to recapitalize it — and it’s expensive, sure, but the way that i view it, it’s an insurance policy for our national survival.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.