What Will New Bomber Squadrons Mean For Air Force? 75 More B-21s?

Posted on

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Goldfein and SecAF Heather Wilson testify

AFA: Perhaps the biggest money — and strategy — question of the new Air Force plan to build 74 new squadrons is: how many B-21 Raiders and people will they need to fill five new bomber squadrons?

The standard answer being proffered by the Air Force Chief off Staff, Gen. David Goldfein, and the head of Air Force Global Strike Command, Gen. Timothy Ray, is that the service doesn’t know how many planes it needs to buy for the squadrons. Goldfein just told reporters here that the service looked at the number of people needed to meet the National Defense Strategy and isn’t yet sure of the number of “tails” that will fill each squadron.

Ray told me he didn’t know the number yet and wasn’t sure when the service would know precisely how many bombers it needs — no matter how possible timelines I offered him.

So let’s engage in what lawyers call informed speculation, based on those increasingly hard to find things called facts.

As I understand from conversations with a number of former bomber commanders and pilots here, a bomber squadron normally comprises 12 combat aircraft ready to fly, with two or three planes as backup to handle the normal cycle of maintenance and repair. They are manned by 1.5 to two times the number of crews needed to fly each plane.

So, if there are going to be five new bomber squadrons by 2030, there will probably need to be an additional 75 B-21 bombers bought. The previous estimate was that the country needed 165 bombers: B-52s, B-1s, B-2s and B-21s in some mix. Since the Air Force already plans to buy “at least” 100 B-21s, it’s pretty easy to assume it will have to buy six dozen or so more B-21s.

Of course, it’s possible that the highly classified aircraft will boast higher sortie rates or Concepts of Operations that allow the use of fewer aircraft in a squadron, but we don’t know that yet.

Each B-21, which Air Force leaders say is on budget and on schedule, will cost $511 million each in 2010 dollars. So simple math says $38.3 billion for another 75, but the cost per aircraft will almost certainly come down significantly if the contractors actually get to build that many planes. (The main reason the B-2 stealth bomber notoriously cost $2 billion apiece is that we cut the buy off at 21, spreading the fixed R&D and infrastructure costs over a tiny fleet). Yes, Congress likes to buy aircraft, but regardless of the final number, it’s a considerable amount of money to discuss at any time, let alone just when the Budget Control Act is once again raising its ugly head, with strict caps returning in 2020 and beyond.

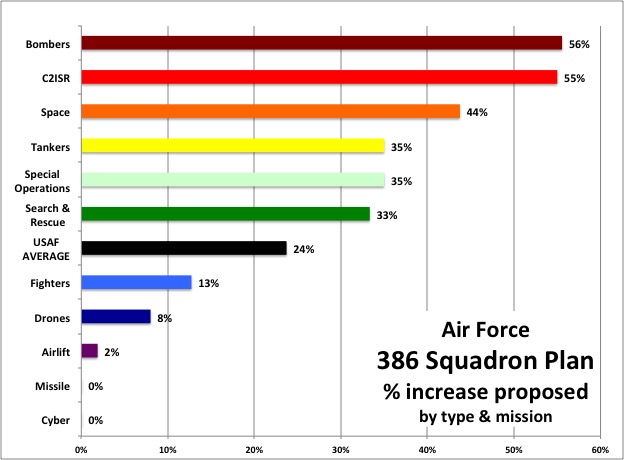

And while the bomber force gets the largest percentage increase under the proposed plan, it’s still a relatively small part of the force, going from nine squadrons to 14.

- Space forces — which may split off into their own service — will grow by seven squadrons (to a total of 23), as will Air Force Special Operations (growing to 27), and fighters (to 62).

- Combat Search & Rescue (CSAR) grows by nine squadrons (to 36);

- tanker squadrons, like the KC-46, will grow by 14 squadrons (to 54),

- and Command & Control, Intelligence, Surveillance, & Reconnaissance (C4ISR) — such as JSTARS and whatever replaces it, probably a family of drones — will grow by a staggering 22 squadrons, to a total of 62.

Of course the bombers will be the most expensive plane for plane, but there’ll be a lot more planes of other types, and they add up.

So reporters kept pressing Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson and Goldfein here for answers to the reasonable question: how will the Air Force afford 74 more squadrons with all the people, planes, satellites, and infrastructure needed to make them useful? Wilson told us that the service was engaged in a “conversation” with Congress and the American people about just what is needed to manage today’s great power competition with Russia and China outlined so clearly in the National Defense Strategy.

While that seems fair and reasonable, it may not be politically sustainable, especially if the federal deficit continues to rise geometrically. However, Defense Secretary James Mattis, who has pressed the services to estimate force structure based on strategy — not budget — deserves much credit for doing what virtually every military officer and expert has urged for decades.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.