What’s Likely in New Pentagon Strategy: 2 Theaters, Fewer Bases, A2AD

Posted on

The threat of a $500 billion defense sequestration looms as a result of the Super Committee failure – a prospect that Secretary Panetta has called “potentially ruinous.” Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee Representative Howard “Buck” McKeon and some of his Senate colleagues have promised to introduce legislation to reverse the cuts.

Meanwhile, the Pentagon is in the midst of a “comprehensive strategic review” designed to bring missions and resources into alignment with dramatically reduced budgets relative to what the military had expected to receive just two short years ago.

Principles and Pillars of the Forthcoming Strategy

The first flaw in this approach is that it ignores the fact that the defense budget has already been cut and will be cut again before this latest strategic review is completed. This means that military and defense officials are chasing budget numbers that have been determined in a vacuum and are attempting to identify a strategy to match. Much of this is Congress’ fault, however, so the blame must be shared across the Potomac.

Military leaders will be asked to undertake yet another strategic review once this latest one is done, just over one year later at the beginning of the next presidential term regardless of who occupies the White House. All this creates a debilitating state of seemingly endless strategic review by Pentagon leaders that only serve to compound the challenges posed when strategy changes faster than force structure. Nonetheless, some general assumptions can be made about the military initiatives most likely to be sacrificed.

This latest review process has two noticeable differences:

• The fact that DoD is operating under strict budget constraints when translating stated roles into capabilities, and

• The drawdown of military personnel in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The 2010 QDR identified four priority objectives:

• Prevail in today’s wars,

• Prevent and deter conflict,

• Prepare to defeat adversaries and succeed in a wide range of contingencies, and

• Preserve and enhance the all-volunteer force.

The new strategy will be published roughly one year after the 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) and three years after the National Defense Strategy and the Quadrennial Roles and Missions Review. The short time between the QDR and the latest review does not lend itself to major changes, especially given that they will still be using the same National Security Strategy as overarching guidance.

Assuming the Secretary Panetta does not decide to concede U.S. leadership role in the world, the latter three are unlikely to change. The first objective, prevailing in today’s wars, will most likely undergo the greatest spending adjustments. The Army and Marine Corps already face cuts in terms of size and force structure, but they will be shrinking further even before the threat of sequestration.

Development of AirSea Battle, a new operational concept, will also significantly affect the services’ investment portfolios. Traditionally, the Navy, Army, and Air Force have each received about one-third of the budget. This will probably not continue. Secretary Panetta and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have indicated that the Air Force and Navy would bear a smaller portion of the cuts. However, these services, particularly the Air Force, are starting from a much lower baseline. Any change in the “golden ratio” is relative because the Air Force and Navy have largely been bill payers for the Army over the past decade as the ground forces prosecuted land-heavy operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Overseas Presence and Bases Will Be Cut, Especially in Europe

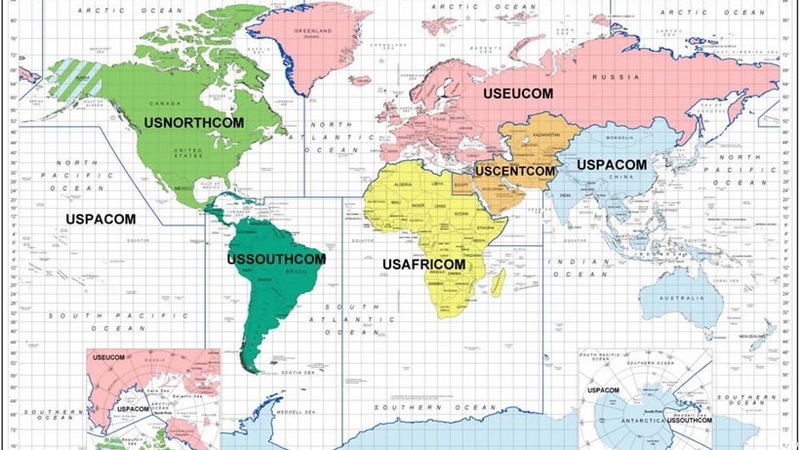

U.S. forces in Europe will be reduced as part of the Pentagon’s strategic review outcomes. That is because, with the budget axe falling so fast and so deeply, the Pentagon will be forced to fiercely prioritize the military presence in foreign regions. Secretary Panetta betrayed a zero sum approach in alluding to force cuts in Europe in part to “free up money so the United States could maintain or increase its forces in Asia.”

Changes in U.S. priorities abroad will affect U.S. facilities and bases there, as well as at home. In a November New York Times interview, Secretary Panetta mentioned the possibility (read: likelihood) of another round of base closings. He later identified Air Force air wings as specific force structure that is over capacity. This is no surprise given that senior Air Force leaders have long said there is excess overseas inventory. Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Admiral Mullen went so far as to say all of DoD was “overcapacitized (sic) by about 20 percent. And I’m paying the bill for those lights and that energy and those people to keep those places open.” What Secretary Panetta did not mention in is interview was reduction of Army installations and presence in Europe, something that has been underway for the last decade and will doubtless continue.

What is not being discussed in all this, however, is the critical role our European bases play in U.S. power projection and what that loss would mean for the military elsewhere. Forward deployment in Europe allowed America to respond quickly following 9/11 and to treat injured soldiers in Germany returning from the front lines that saved countless lives. Our European bases and presence made it possible in part to prosecute an air war over the skies of Libya on short notice. Preserving America’s current overseas posture, including bases in Europe, serves our national interests but they may well be deemed unaffordable in the latest strategy.

Ground Forces Will Fall Below Pre-9/11 Levels Quickly

The Obama Administration’s “strategic pivot” from the Middle East to the Pacific will feature prominently in the upcoming review. This larger change is manifest through several interconnected shifts. The first is a large-scale reduction in ground forces. The Army currently plans to cut 50,000 soldiers, reducing its active duty end strength from 570,000 to 520,000. General Dempsey said that number will likely get bigger to meet ever more budget cuts. Similarly, the Marine Corps is planning for a reduction of roughly 15,000 Marines from 202,000 to 186,600. According to Panetta, much steeper cuts beyond these are likely.

Even though the Pentagon is cutting ground forces, DoD seems set to somehow revive the long-derided but durable two-war standard by another name. This will be a paper standard only meant to symbolize the U.S. military is still a global force with global reach. Whatever the new force-planning construct is called, it will surely be couched in language similar to the muddled force-planning construct that emerged from the 2010 QDR that actually added uncertainty to and removed long-standing guidance from the military services.

Active, Guard, Reserve Mix to Change Under Banner of “Reversibility”

As General Dempsey has argued, the United States must not find itself in a position where it can do only one thing at once. This is obvious. Pentagon leaders plan to skirt the lack of capabilities to make this possible through an increased reliance on National Guard and Reserve forces. DoD plans to assume more risk in the active component and the capabilities available immediately in the event of conflict or crisis. Examples include heavy armor brigades and tactical fighter wings. Readiness will also be resourced differently so the Army’s Force Generation model appears likely to also be deemed unaffordable.

The problem is that this seems more like wishful thinking than strategy. While the “operational Reserve” has preformed remarkably well in Iraq and Afghanistan, the last decade of war has stressed all of America’s forces — active duty, reserve, and National Guard-to the breaking point. If the military’s senior leaders still feel that the two-war standard is important to maintain, they should mandate the necessary resources. Trying to accomplish the same mission set with fewer resources is budgetary sleight of hand, not a plan, and certainly not a comprehensive strategy.

Counterinsurgency Wanes While Counterterrorism Waxes

Another tenet of the “pivot” to Asia is the transition from a military focused on manpower-intensive counterinsurgency (COIN) to the light footprint doctrine of counterterrorism (CT). Secretary Panetta has mentioned unmanned or remotely piloted aircraft, cyber and Special Forces as key areas that must be protected from budget cuts. They may even get more money.

General Dempsey has called for the greater “integration of general operating forces and special operating forces.” These focus areas reflect a strategy that will increasingly seek to defeat threats “over-the-horizon” with highly-targeted mobile operations. Drone strikes have proven especially useful in areas where it is imprudent to send large American forces such as northwest Pakistan. Special Forces can continue playing a lead role in both covert operations and foreign internal defense capacity building with partner nations.

The challenge is that special operations forces are, by definition, not scaleable. It is also unclear that a small group of highly-skilled operators can sustain an operational tempo that grows every year. While some in Congress have been concerned about the readiness of the U.S. military and troops on their fifth or sixth combat tour, many special forces operators have already served 10 or more overseas combat tours. That pace is unsustainable with even marginal growth of SOF.

The Congressional Research Service has summarized succinctly in a July 15th report how cuts in the active duty ground forces will hurt special forces, not help: “Because USSOCOM draws its operators and support troops from the services, it will have a smaller force pool from which to draw its members. Another implication is that these force reductions might also have an impact on the creation and sustainment of Army and Marine Corps “enabling” units that USSOCOM is seeking to support operations.”

While drones are incredibly useful in remote, undefended areas, these systems are not a panacea. Most military’s drones still need pilots manning stealthy air superiority tactical fighters as fifth-generation Joint Strike Fighters to clear the skies. But those F-35 jets are a huge bulls eye in the latest strategic review.

While a counterterror-heavy strategy might save money in the short-term, it is an open and risky question whether counterterror capabilities will be as effective as its advocates claim. COIN can take years to reverse insurgent gains and provide a blanket of security for the local population. However, once local government and security forces reach a certain level of competence, insurgent forces tend to fade away. CT involves less of a commitment and places fewer personnel at risk, but in some cases offers a lower goalpost. Nor can counterterror capabilities alone comprehensively address the root causes of insurgency or terrorism with its focus on killing or capturing bad guys when they emerge.

The strategy’s tilt on COIN versus CT will depend on whether it emphasizes threats from radical Islam or the challenge of rising near-peer competitors. If the Pentagon’s primary concern is radical Islam, COIN probably offers the better long-term path to a stable Middle East because it addresses the root causes of insurgency. However, the Pentagon is more likely to emphasize counterterrorism at the expense of counterinsurgency as part of the shift in priorities from the Middle East to East Asia, theoretically freeing up resources to acquire capabilities that may excel in anti-access and area-denial environments.

Bomber Survives, Cyber Grows

For all the questions about the trade-offs needed for the Pacific “pivot” to work, such a shift might be smart planning were it not zero-sum. As China’s economy and military power continue to expand, the Chinese will naturally grow more assertive internationally. As China flexes its muscles throughout the Asia-Pacific — a process already well underway — it will likely come into some sort of diplomatic standoff with American allies and perhaps even the United States itself.

The United States is poorly equipped for such a confrontation, a problem the new strategy will surely not fix. China is currently building a complex network of anti-access and area-denial platforms designed to inhibit American operations along the Chinese littoral. Chinese anti-ship ballistic missiles, advanced radars, and precision targeting could turn non-stealthy U.S. platforms into multibillion-dollar targets. In order to knock out Chinese air defense and missile installations – – or at the very least, to hold these kinds of targets at risk — America needs more submarines and a next-generation long range strike bomber and its associated capabilities. While the bomber will receive a prominent endorsement in the strategy and the 2013 defense budget, it will come at great cost to other programs, priorities and end-strength for the Air Force. Zero-sum outcomes will apply not only to geographic regions but to programs such as aircraft and shipbuilding as part of the latest strategy review.

The irony unlikely to be addressed in the Pentagon’s comprehensive review is that transforming the American military arsenal from one designed to deter and fight wars with assured access to one designed to excel when access is challenged will not be cheap. Consequently, a key dilemma is that it is not enough to simply move more forces to Asia. The United States must invest strategically and focus on buying platforms and developing cutting-edge capabilities that will be important in the future, and not merely those on which we have relied in the past.

Along with a heightened focus on the Pacific, the Pentagon will protect funding for both offensive and defensive cyber warfare. The Chinese have long viewed intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance abilities as the linchpin of American dominance. While battlefield awareness acts as an enormous force multiplier for American soldiers, reliance on high-tech satellite imaging, networked communications, and systems of systems has made the military increasingly vulnerable to cyber attacks. In the future, it is not ridiculous to imagine a scenario where an enemy power could take an entire American installation such as Guam offline with a single cyber attack. Investing in cyber capabilities and technologies clearly makes sense for the Pentagon. This should theoretically protect many U.S. military space and satellite assets; however, these too will fall victim to budget cuts at a time when the U.S. needs to harden and multiply its space and satellite systems.

Decaying Nuclear Arsenal to Take More Hits

One of the more troubling aspects of the emerging comprehensive review is that it will more than likely propose further cuts to America’s nuclear warhead stockpile. While the New START treaty featured unilateral American disarmament vis-à-vis Russia — caps were placed below the level of American warheads but above Russian levels — it ignored the growing Chinese nuclear arsenal. Hidden within thousands of miles of underground tunnels, the Chinese could conceivably have a nuclear arsenal approaching the same scale as the United States and Russia.

While the Russians and the Chinese have built new nuclear warheads as new technologies have emerged, the U.S. has upgraded its arsenal instead of building new warheads. As the scientists who developed and maintained America’s nuclear arsenal throughout the Cold War retire, the U.S. is left with the very real scenario of having an inexperienced workforce left to preside over a portfolio of weapons that are so heavily modified from their original design that we simply do not know how they would hold up if they would be used. As former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates observed, “to be blunt, there is absolutely no way we can maintain a credible deterrent and reduce the number of weapons in our stockpile without either resorting to testing or pursuing a modernization program.”

The strategy review will be silent about resuming testing or modernization, but it will undoubtedly cite the need to reduce resources for America’s nuclear arsenal. In the 1950s, the Eisenhower administration cut ground forces but made up for these cuts by expanding America’s nuclear arsenal as a hedge against foreign aggression. Today, we are threatening to cut conventional forces while at the same time cutting the strategic forces. Don’t expect this schizophrenic solution set to be addressed in the new strategy.

Neither Comprehensive Nor Strategic

The early details emerging from the Pentagon’s strategic review are promising but so far lack the sort of strategic underpinning that department leaders have promised. Simply shifting fewer resources and platforms to Asia will not be good enough. If America truly wants to take part in the “Pacific Century,” the military must change in a way that can address given the changing nature of the East Asian balance.

Unfortunately, the way DoD is preparing for this shift seems to be driven more by budgets than by strategy. Defense officials should not shoulder all the blame. A truly comprehensive review would boil down America’s key activities into a concrete list of five or six enduring advantages and then think about how the U.S. can maintain these core competencies into the future. Such a self-aware list might be asking too much from the Pentagon, but it would be a good start and a more effective path to plotting America’s future defense strategy than simply by picking off low-hanging but vital fruit such as nuclear modernization.

Mackenzie Eaglen, a member of the Breaking Defense Board of Contributors, is a former congressional staffer and defense analyst at the conservative Heritage Foundation.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.