What Lessons Do China’s Island Bases Offer The US Army?

Posted on

Graphic courtesy Sen. Dan Sullivan

WASHINGTON: If ground forces are obsolete, why are the Chinese bothering to build all those artificial islands in the South China Sea? The answer to that is key to the US Army’s emerging vision of its future role, a complex combination of old-fashioned close combat, resilient wireless networks, and advanced long-range weapons that extend the Army’s reach well beyond the land.

Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster signs his book “Dereliction of Duty” for a fan at CSIS

China is “building land… to project power outward from land into the maritime and aerospace domains,” the Army’s chief futurist, Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, argued yesterday at the Center for Strategic & International Studies. Much like the Japanese in World War II, he said, the Chinese see island bases as a means to dominate the seas and airspace around them, allowing them to sink ships and down aircraft. The Chinese strategy has only become more effective in the modern era with the proliferation of long-range precision-guided missiles.

The US Army needs to do as the Chinese have done, McMaster said. For decades, the Air Force and Navy have projected power onto the land to support the Army with airstrikes, reconnaissance, and jamming: Now the Army must develop the capability to project power “cross-domain” from the land into the air, sea, space, and cyberspace to support the Air Force and Navy.

Army 155 mm howitzer

Expanding Future Army Fires

For example, said McMaster, future US Army “fires” units must go beyond traditional artillery and use long-range weapons to engage distant targets on the land, in the air, and on the sea. The Army must also be able to provide its own fire support, electronic warfare, and air defense, he said, rather than relying on hot and cold running airpower.

The Army can no longer count on Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps pilots to dominate the skies in the face of advanced anti-aircraft systems and proliferating drones. “I never had to look up, in my whole career, and say ‘Is it friendly or enemy?'” McMaster said. “We have to do that now.”

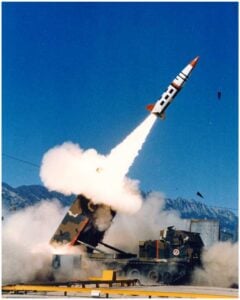

Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) launch

McMaster’s command, the Army Capabilities Integration Center (ARCIC) of the Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), has run a long series of classified wargames on future technologies, tactics, and organizations. “We look across all domains…air, land, sea, space, and cyber,” and bring in wargamers from the other services and allied nations, said Col. Wayne Grieme, chief of ARCIC’s Joint & Army Experimentation Division (JAED), in a call with reporters yesterday afternoon.

In these scenarios, said JAED’s chief scientist, Van Brewer, “the operationally significant impact of increased range [for weapons] really changes how the Army projects power — land, sea, air.”

But currently the US military doesn’t have any land-based anti-ship missiles, I noted in the Q&A with McMaster. Meanwhile our land-based land-attack missiles are limited in range by the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty, which Russia has violated and China never signed. How much of this vision can we make real?

“The physical fires part of it is not as hard as you think,” McMaster responded. “There might be ways to use existing systems in new ways.”

McMaster didn’t give specifics, but one example that Defense Secretary Ash Carter and Deputy Secretary Bob Work have enthused over is the Hyper Velocity Projectile. The HVP is a precision-guided shell that can be fired from traditional artillery and naval cannons to give vastly greater range against a wide variety of targets, including ships at sea and potentially even incoming cruise missiles. Carter and Work have also extolled how the Navy has repurposed its Tomahawk Land Attack Missile to hit moving ships at sea, which could be a model for modifications for the Army’s ATACMS missile.

“What’s really powerful is the vision from the Secretary of Defense and the Deputy Secretary,” said McMaster. “That’s galvanized action within the services and between the services.”

Robert Work

Making The “Battle Network” Actually Work

The crucial element of this vision isn’t any specific missile, McMaster said, but the joint network that connects the different services so they can assist each other. “It’s about the information collection systems and analytical tools [to] fight effectively as a joint force,” he said.

Currently, for example, the Army is developing its IBCS network so that any missile defense launcher — Patriot, THAAD, maybe future laser weapons — can engage targets using data from any radar. Meanwhile, the Navy NIFC-CA network allows a ship to shoot an incoming missile or aircraft that its onboard radars can’t see, using targeting data from another vessel or a Navy airplane. But those networks are service-specific, not joint, and they’re designed for air and missile defense, not offensive warfare. The goal is a network so flexible and all-encompassing that, for example, a US or allied aircraft can spot an enemy ship, then pass the targeting information to a land-based missile battery to sink it.

An idealized “battle network” consists of three overlapping layers or “grids,” Deputy Secretary Work told an Atlantic Council conference on Monday:

- a “sensor grid” to perceive the battlespace with everything from radar satellites in space to infrared sensors on the ground;

- a “C4I grid” (Command, Control, Communications, Computers, & Intelligence) to pull all the data together and make sense of it; and

- an “effects grid” to reach out and touch the targets, whether with physical high explosive, laser beams, radio/radio jamming, cyber attack, or other means.

This isn’t some hypothetical future, Work said, but an imminent reality if the United States has to go up against an adversary like Russia or China with the sophisticated layered defenses known as A2/AD. “Anti-Access/Area Denial is shorthand for network on network warfare,” Work said. “It’s when your battle network collides against another one, both of them are able to fire guided munitions at advanced ranges, both of them are able to get a good sense on what’s happening in the environment, [and generally] anything that…can be seen can be hit.”

An Army soldier sets up a highband antenna.

In such a conflict, of course, the invisible war of electrons to deceive sensors, jam transmissions and to hack computers is at least as important as the physical battle. You can’t count on your network always working against a sophisticated adversary — and with the rapid spread of information technology, a sophisticated adversary need not be a nation-state.

“Cyber is a very democratic domain,” said ARCIC’s Van Brewer. “With very cheap, accessible capabilities, our enemies can operate and be effective in the cyber domain.”

“The threat — or anybody else — always has an off switch,” said Col. Grieme.

So our networks must be designed to degrade gracefully, Work said, and our minds must be able to cope with losing them. Local commanders must be ready to fight in the dark on their own initiative, guided by a common understanding of the mission and a deep trust in their comrades. “You can configure your network in different ways,” he said, “but you have to be ready for the network to kind of disassemble, and then people to operate on a local level.”

Right now, we’re not ready for such scenarios, McMaster made clear. “We’ve developed systems that are exquisite and could be prone to catastrophic failures” instead of degrading gracefully, he said. The fragility and complexity of existing networks is such, he added to rueful laughter, that some of them don’t need an enemy to break them. They just go down in day-to-day operations without facing hostile action of any kind.

Many existing systems also broadcast continually in all directions at high power, he said. Against a sophisticated enemy, that’s basically putting up big flashing neon arrows labeled “WE ARE HERE.” We need to relearn techniques for concealment, camouflage, and deception — in the visual, infra-red, and radio frequencies of the electromagnetic spectrum — that our adversaries have been refining for years.

McMaster warned that, “our enemies have become more and more elusive, and we’ve become almost transparent.”

Close Combat Remains Relevant

Inspired in large part by Russian successes against Ukraine, McMaster said, “we’re doing a vulnerability assessment on our force. What are we vulnerable to? — (and) topping that list is cyber and electronic warfare.”

That vulnerability means you can never be sure your sensors won’t be blinded or your intelligence deceived — which means, in turn, that your long-range precision-guided weapons will sometimes go to precisely the wrong place. Then you need to send in the ground troops to “develop situational awareness in close contact with the enemy [and] the population,” McMaster said. Even with the most advanced long-range technology, he said, at some point, “you’ll probably have a close fight.”

“This is not just about fires, it’s about maneuver,” said McMaster. “You can’t just stand at a distance and shoot, you have to keep moving to outflank, bypass, or close with the enemy, constantly presenting him with “multiple dilemmas.”

“We’re working very closely with the Marine Corps in particular” on future maneuver by dispersed yet mutually supporting units, McMaster said.

Adversaries will likely hide in populated areas, where the presence of civilians restricts US use of heavy weapons and the clutter of buildings blocks our sensors. In such future fights, all the counterinsurgency and counterterrorism lessons the US has learned so painfully since 9/11 will still apply.

“We’ve always had to do these missions,” McMaster said — the Army’s history of counterinsurgency goes back to the Whiskey Rebellion and the Indian Wars — and they’ll always come up in the future as well, for the simple reason that human beings only live on land. “Until dolphins become… an adversary,” he said, “we’ll always have to deal with the land domain.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.