US On China: Cooperate Where We Can, Confront Where We Must

Posted on

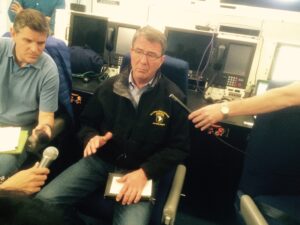

(L-R) Adm. Jonathan Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations; Adm. Harry Harris, commander of Pacific Command; and Defense Secretary Ashton Carter at the 2016 Shangri-la Dialogue.

SINGAPORE: In his speech to the Shangri-La Dialogue here, Defense Secretary Ashton Carter laid out a cautious and carefully crafted vision for security in Asia. Carter called for an “inclusive (and) principled security network,” one that would try to include China and encourage it to abide by international law, rather than seeking to confront and isolate it.

The secretary did warn China against “provocative and destabilizing” actions, notably such as building artificial islands in the Scarborough Shoal off the Philippines. But he and other Pentagon leaders here also took pains to emphasize positives, such as China’s participation in the 27-nation Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercises.

“Some of China’s behavior is having the effect of self-exclusion on their part,” Carter told reporters this afternoon, “(but) we hope that every country, including China, chooses to be part of the network and not to exclude themselves.”

“We’ve seen positive behavior in the last several months with China,” added Admiral Harry Harris, the head of the Pacific Command, not once to mince words on Chinese behavior. “Every now and then we’ll see an incident in the air that we may judge to be unsafe, but those are really, over the course of time, rare (and the two militaries meet) to work through these incidents.”

“We have a set of rules by which we have agreed to behave together, (CUES), the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea,” agreed Adm. Jonathan Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations. “More and more of our encounters are completely consistent with that code: They are routine, safe, and professional, (although) every now and then we’ve got an outlier.”

That said, “we want to cooperate with China in all domains as much as possible… but we have to confront them if we must,” Harris warned. “I would rather we didn’t have to.”

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states.

The Regional Tightrope

Such words may seem too weak for China hawks like Senator John McCain, who wants China to stay out of RIMPAC and just yesterday called the administration’s efforts in South China Sea inadequate. But these statements aren’t aimed at a domestic audience: They’re meant to reassure regional partners who want the US to protect them from China without escalating conflict against what remains their largest trade partner.

Singapore, for instance, has gotten far ahead of other Southeast Asian nations in allowing US forces to operate from its soil, hosting regular deployments of Littoral Combat Ships and, as of December, P-8 Poseidon patrol planes. Yet at the same time, “Singapore has a critical important economic relationship with China,” said Bonnie Glaser, head of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic & International Studies. “Singapore is concerned about the pattern of Chinese coerciveness in the region…and wants the United States to push back harder, but I don’t think Singapore really wants to be part of that pushback in any overt way.”

Such ambivalence in the region, even from our most consistent partner, requires American action and rhetoric alike to walk a tightrope, as evident in Carter’s carefully chosen language today. The US has to speak strongly enough to China to reassure the smaller powers of the region they won’t be bulldozed by Beijing, but not so strongly they fear the two great powers will clash with them in the middle.

“That’s a balance that the US is always trying to strike,” Glaser said. “It’s a real challenge, especially here when all the countries that are present at this kind of meeting, they don’t agree on what they want from the United States.”

Secretary Carter’s “inclusive network” is trying to bring in a tremendously diverse array of countries. They range from Shangri-la host Singapore, a prosperous and quasi-democratic city state, to Anglophone nations like Australia and New Zealand; longtime Asian allies like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan; new partners like giant, democratic India and small, authoritarian Vietnam; and Southeast Asian neutrals like Indonesia.

Why bother herding all these cats? “At the end of the day the United States cannot shape China’s choices by itself, (or) even with the involvement of other external (to Southeast Asia) actors like Japan and Australia and even India,” Glaser said. “It really as to be greater commitment by states in the region themselves.”

Defense Secretary Ash Carter speaks to reporters en route to Singapore.

Words Matter

“By the latest count, you’ve used word ‘principle’ 37 times,” one questioner told Carter after his remarks this morning. “That of course did not happen by chance.” The secretary replied using the word a 38th time — but what did Carter mean?

“Peacefulness, lawfulness, freedom of the commons,” Carter said at his press conference. “Freedom from coercion, the ability for each country to make its own choices; for disputes to be resolved peacefully; for countries to work together cooperatively and not against one another in the military sphere to solve many of these problem that we all share in common,” from disaster relief to combating terrorism and piracy.

That principle of cooperation brings us to the “network,” another carefully chosen and oft-repeated word (also 37 times, by my count). Historically, America’s paradigm of partnership was NATO, an unified international command led by a US officer and founded on a formal treaty of alliance. By contrast, in Asia, the US relied on a “hub and spoke” system of alliances, in which America guaranteed the security of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and (these two in a single treaty) Australia and New Zealand, without these partners pledging to protect each other. Most countries, such as Singapore, preferred to cooperate with the US outside a formal treaty framework, and even those that signed treaties rarely accepted a standing international command structure, with the prominent exception of South Korea.

Carter’s use of the word “network” threads a needle. On the one hand, it embraces the more informal nature of security cooperation in Asia, rather than trying to impose a NATO model. On the other, it emphasizes the multilateral ties the region’s nations have to one another, not just the bilateral arrangements with the US.

“Peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific has never been maintained by a region-wide, formal structure comparable to NATO in Europe. That’s made sense for this region,” Carter said in his speech. “And yet, as the region continues to change, and becomes more interconnected politically and economically, the region’s militaries are also coming together in new ways.”

So while Carter carefully listed achievements in bilateral US collaboration with Japan, Australia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and India, he spent as much time on multilateral partnerships. He announced, for example, that Japan and South Korea — whose relationship is still embittered by 35 years of brutal colonization, despite the common threat from North Korean missiles — would join the US in “a trilateral ballistic missile warning exercise,” codenamed Pacific Dragon, “later this month.”

Carter extolled other trilaterals too. “We’ve agreed to hold, and begun planning on, additional US-Japan-Australia trilateral exercises,” he said. The US-Japan-India Malabar exercises continue. The US, Thailand, and Laos are working on explosive ordnance removal of old unexploded bombs. Better yet, from the perspective of a US eager to share the burden of regional defense, countries are coming together on their own: Japan is equipping the Philippines, while Japan and India are assisting Vietnam with equipment, training, and exercises.

The sheer diversity of the countries involved in these initiatives speaks to Carter’s objective of “inclusiveness.” But the primary target to “include” is China.

“The United States welcomes the emergence of a peaceful, stable, and prosperous China that plays a responsible role in the region’s principled security network,” Carter said his speech. “We know China’s inclusion makes for a stronger network and a more stable, secure, and prosperous region.”

Conversely, to the extent China is excluded and isolated, that’s the consequence of its own actions in the South China Sea and elsewhere, Carter said repeatedly. “As their concern grows over this kind of activity, increasingly nations in the region are cooperating on maritime security among themselves and coming to the United States for additional assistance and support,” Carter said at the press conference. “That is having the effect of China isolating itself in the region.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.