US Needs New Strategy To Combat Russian, Chinese ‘Political Warfare’: CSBA

Posted on

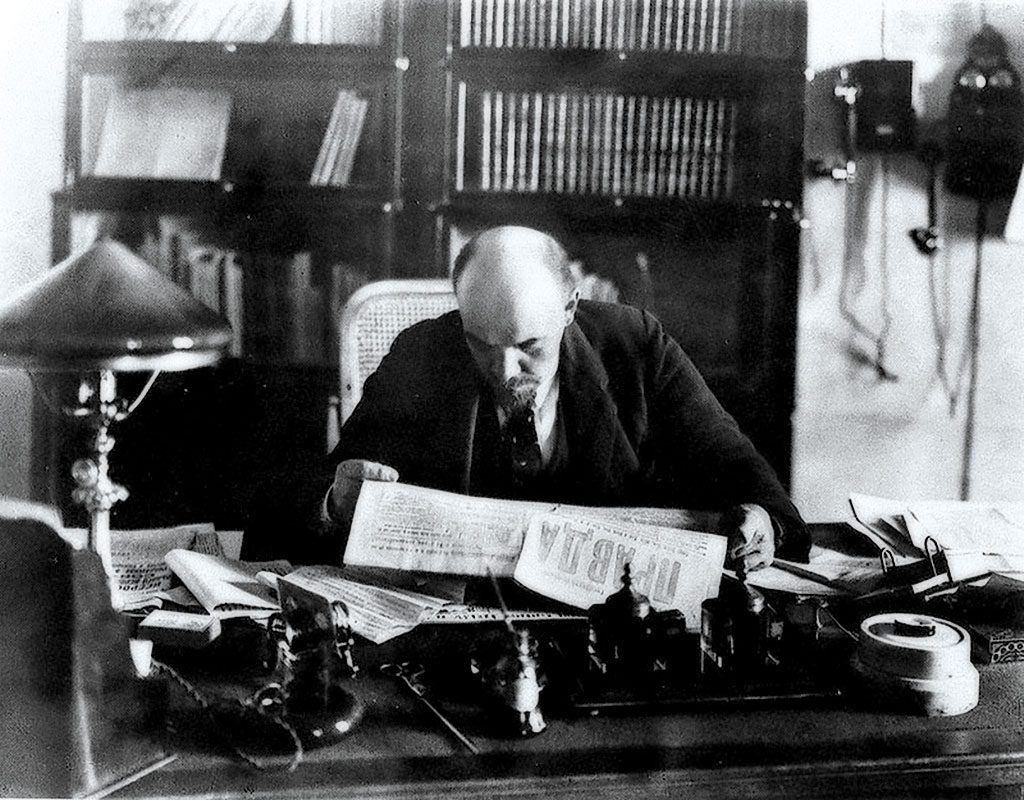

Vladimir Lenin pores over the newspaper in his Kremlin office. Contemporary Russian and Chinese political warfare has its roots in Lenin’s strategy of the 1920s.

WASHINGTON: Russia’s meddling in the 2016 elections is just the tip of an iceberg of ongoing, systematic subversion, argues a new report released today. From Beijing’s bullying of Chinese students abroad, forcing them to lobby for the regime on matters like Taiwan and Tibet, to Moscow’s online support for radicals in Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands, both Russia and China are waging political warfare worldwide in ways democracies are ill-equipped to deal with, says the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments.

The West needs a new strategy, CSBA says — starting with a better intellectual framework for what’s going on than “competition.” While the report doesn’t criticize Defense Secretary Jim Mattis directly, his National Defense Strategy consistently talks about “strategic competition.” But competition implies rules, for one thing, which Moscow and Beijing don’t accept.

Tom Mahnken

“To many in the West, ‘competition’ is coming to be viewed as synonymous with ‘peacetime,’ and competition and conflict are seen as mutually exclusive,” lead author Thomas Mahnken told me. “The Chinese and particularly the Russians reject this dichotomy: They see themselves as being in conflict with us today.”

While the two countries are different in many ways, the study argues they practice similar strategies that are rooted in their violent political history, their common Communist past and, ultimately, 19th century German theorists like Marx and Clausewitz. If war is politics by other means, this worldview says, then politics is war by other means. And political warfare must be conducted with the same ruthless ingenuity as open war because the stakes are equally high: the survival or destruction of the regime.

Moscow and Beijing are both driven by fear, the report emphasizes. Elites in both countries grew up during the Cold War against the United States and blamed America for undermining their regimes. Putin and his ex-KGB cohorts saw the Soviet Union collapse around them. Xi and his fellow sons of the Mao generation saw Communist rule suffer a “near death experience” in Tiananmen Square.

In the decades of American triumphalism that followed, Moscow and Beijing saw the US overthrow regimes in Afghanistan and Iraq with its own military while supporting pro-democracy movements elsewhere. When Russian Chief of Staff Gen. Valery Gerasimov said in 2013 that “the trend in the 21st century is to erase the line between war and peace,” he was diagnosing what he thought the West was doing as much as he was prescribing a strategy for Russia.

“They grossly understated the powerful domestic drivers behind the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the color revolutions, and the Arab Spring,” the report writes. “They also dramatically overstated the roles of Western agencies in each of these cases.”

For Putin and Xi, therefore, their campaigns of subversion against democracies are arguably defensive, just a proportionate response to the insidious Western influence they see challenging their regimes every day. (That very little of this Western influence is government-directed — that, indeed, its lack of top-down leadership is its great strength — is fundamentally difficult for authoritarians to understand).

“Both Russia and China perceive Western democracy promotion, official and unofficial, as an attempt to overthrow their regimes,” Mahnken said. “Indeed, they see Western political warfare as being part of the ‘American Way of War.'”

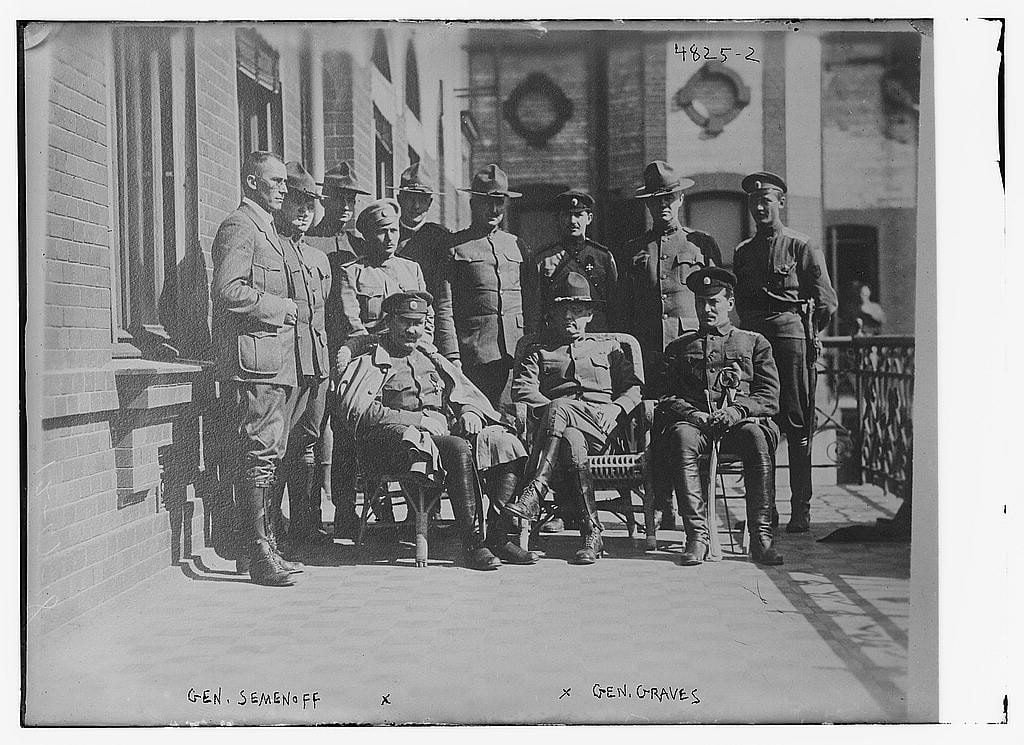

The commander of US intervention forces in Russia, Maj. Gen. William Graves, meets with anti-Communist warlord Grigory Semyonov.

A Heritage of Fear

This culture of fear long predates the current leaders or even the Cold War, however. Both Russia and China have long histories of foreign invasion and civil strife, whose lingering trauma can be hard for relatively blessed Americans to appreciate. Both countries’ leaders grew up under Communist regimes, which established themselves through brutal civil wars and were encircled by hostile powers. It’s worth remembering that US troops landed in Russia as part of a short-lived intervention after World War I and, before Harry Truman fired him, Douglas MacArthur wanted to win the Korean War by invading China, probably using nukes.

This history is very much alive in Moscow and Beijing. The Chinese Communist Party, for example, still has a major division dedicated to the “United Front”: That’s a concept and catchphrase that dates back to Vladimir Lenin’s efforts to align with (and manipulate) non-Communist left-wing movements in Europe. Far from being a vestigial relic, the modern United Front Work Department has actually grown in recent months, the report says: “In March 2018, the UFWD acquired even more bureaucratic clout after it subsumed the Religious Affairs Bureau, the State Ethnic Affairs Commission, and the Office of Overseas Chinese Affairs.”

With a significant presence in “United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada,” the report says, the United Front’s modern mission is to influence Chinese communities worldwide, especially mainland Chinese studying abroad, and convince them to publicly support Beijing’s position — if necessary by threatening their families back in China.

And that’s just one arm of political warfare, the report notes: “Other Party organs, including the International Liaison Department and the Ministry of State Security, are more explicitly charged with influencing and intimidating non-ethnic Chinese foreigners.” Then there is the systematic effort to steal US defense secrets and intellectual property.

The Kremlin has a similar array of agencies, from the GRU military intelligence directorate, linked to the Wikileaks hack, to organizations not officially part of government at all, such as “troll farm” Internet Research Agency, indicted by Robert Mueller for its 2016 role.

Indeed, both Russia and China have made sophisticated use of the Internet to sow disinformation and discord. At the same time, they’ve mobilized old-fashioned economic and military coercion in new ways. When South Korea finally agreed to the deployment of a US THAAD missile defense system on its territory, Chinese travel agents systematically deleted South Korea from their offerings, cutting Chinese tourism to some spots by 80 percent, while state-owned companies boycotted Lotte Corporation, which owned the land where THAAD was emplaced, forcing it to sell off its Chinese department stores. Russia has cut off oil and gas supplies to its neighbors dozens of times since 1991 as a tool of economic pressure.

Russian Risk-Taking, Chinese Power

To date, however, only Russia has crossed the line from applying pressure to actively suborning a sovereign state. Its means vary from cyber attacks on the Estonian government in 2007, overt conventional invasion of Georgia in 2008, proxy warfare in Ukraine since 2014, and of course interference in the US election process in 2016. By contrast, China’s most direct actions against the US to date have been flying airplanes dangerously close — something Russia has done as well — and nearly blinding US pilots with lasers.

Russia is considerably more aggressive than China, Mahnken said. That doesn’t necessarily make Russia more dangerous.

First, political warfare can backfire like any other kind: “The Russian leadership’s aggressiveness has begun triggering responses on the part of its current and potential victims, whereas the targets of Chinese political warfare have been slower to awaken to the challenge,” Mahnken said. What’s more, Russia has a much smaller economy, a chronic dependence on oil exports, and declining life expectancies: China is already more powerful and will become more so over time.

That matters particularly because, the occasional Crimea-style coup aside, political warfare is generally a long game. “Both regimes perceive their political warfare campaigns to be a permanent feature of their strategic postures,” the report concludes. “Most operations have been structured (as) a succession of modest incremental steps, all of which are intended to fall below the threshold for Western escalation…..The main goal is not hard victories, but simply sowing doubt, creating confusion, and imposing costs.”

Russia and China are far from unstoppable, and political warfare can be countered like any other kind, Mahnken emphasized. “Indeed, such strategies may produce self-defeating effects,” he said. “But the fact that Russia and China are waging coherent political warfare strategies is a clear contrast with the United States and the West — where attempts to understand Russian and Chinese political warfare is still a work in progress and efforts to counter it nascent at best.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.