Uncertainty & Anxiety About Army’s New Scout Aircraft

Posted on

WASHINGTON: After months of hints, the Army announced Friday it wants competing prototypes of a Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft flying by 2023. But there’s a deal of uncertainty — even anxiety — about what the Army wants.

“Industry can develop whatever the government tells them what they want, if it sticks to the requirements and stops changing its mind on priorities,” said Mike Hirschberg, director of the AHS/Vertical Flight Society. “Industry is leaning forward and has already invested a $1 billion in JMR (the Joint Multi-Role demonstrator), but DoD needs to see this through.”

Companies may get answers to some of their questions on an industry day Thursday in Huntsville, Ala. But in the documents released so far, the budget for FARA is left blank and the requirements remain unclear. Despite inquiries to sources in and out of the Army, I haven’t even been able to clarify whether or not FARA will be part of the joint Future Vertical Lift (FVL) family of aircraft.

Future Vertical Lift: In or Out?

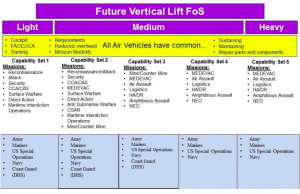

FVL is intended to replace a wide range of current helicopters from light (Capability Set 1) to very heavy (Capability Set 5) with a joint family of designs using common technologies and technical standards. To date, FVL has focused on a mid-sized transport aircraft to replace the UH-60 Black Hawk, known as Capability Set 3, with the Army-led Joint Multi-Role (JMR) initiative funding two prototypes: the Bell V-280 Valor tiltrotor and the Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 Defiant compound helicopter. But the Army has become increasingly concerned about its lack of an light, agile armed scout, so leading generals now say the most urgent need is in Capability Set 1.

The document released Friday states only that the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft will be “comparable in size to what has been described as FVL Capability Set (CS) 1.” But that doesn’t necessary mean it will fulfill other aspects of CS 1, fall under the FVL governance structure, adhere to FVL standards, or follow FVL’s schedule. Indeed, the Army seems to want its scout aircraft sooner than FVL’s target dates in the 2030s, which may mean it doesn’t have time to develop all the advanced technology envisioned for FVL. If the Army does keep the scout aircraft outside the joint FVL structure, it’ll have a lot more flexibility to run the program — for good or ill.

Going outside FVL doesn’t mean starting from scratch. There is one advanced rotorcraft already flying that’s “comparable in size” to FVL Capability Set 1: Sikorsky’s S-97 Raider compound helicopter. That would seem to give Sikorsky a strong lead. But between now and 2023 there’s probably time for Bell to build a scaled-down version of its Valor, as well as for other companies like Kaman, AVX, or Airbus to enter. Plus no one’s sure what the requirements really are yet.

“Over the past five years, Sikorsky has invested $300 million in the S-97 Raider, which it is targeting for this size class,” an industry source said. “Depending on what the requirements are, it probably is the farthest ahead, since it already has a demonstrator flying. But the requirements could be substantially different than the (S-97) aircraft. Bell and other companies have also shown the ability to put together demonstrators quite rapidly, as seen with the Valor.”

That, of course, would require industry having enough confidence in where the program’s going and how it’s funded.

Replacing Kiowa (Again)

Industry has reason to be anxious. The Army has a long and unhappy history of failed attempts to replace the Vietnam-vintage OH-58 Kiowa scout chopper: the Comanche (cancelled 2004), the Arapaho (2008), the Armed Aerial Scout (2013). In 2014, the service decided it couldn’t afford either to keep upgrading the aging Kiowas or to replace them. So the service came up with a bitterly controversial plan to retire the Kiowas and transfer the reconnaissance mission to the much heavier AH-64 Apaches, working with Shadow drones.

“The past year or two has shown that’s not a very good solution,” said retired Maj. Gen. Rudy Ostovich, former commander of the Army aviation center at Fort Rucker. “It’s better than nothing. But it’s not the same as having an armed reconnaissance capability.”

One wrinkle is that “armed reconnaissance” — the traditional definition of the Kiowa’s role — and “attack reconnaissance” — what the Army called for Friday — aren’t the same thing, Ostovich told me. “Attack and reconnaissance — those are two different missions.”

An attack helicopter, like the AH-64 Apache, is meant to press home an attack. It needs heavy armor to take punishment and heavy weapons to dish it out. An armed reconnaissance helicopter is meant to go in, find the enemy and get out. It can fight if it has to — to escape, to force a hidden enemy to reveal himself, or to strike targets of opportunity — but it needs to be small and agile to avoid detection.

So the Army document calls for “a platform sized to hide in RADAR clutter and for the urban canyons of mega cities….This platform is the ‘knife fighter’ of future Army Aviation capabilities, a small form factor platform with maximized performance.”

Multi-Domain Recon

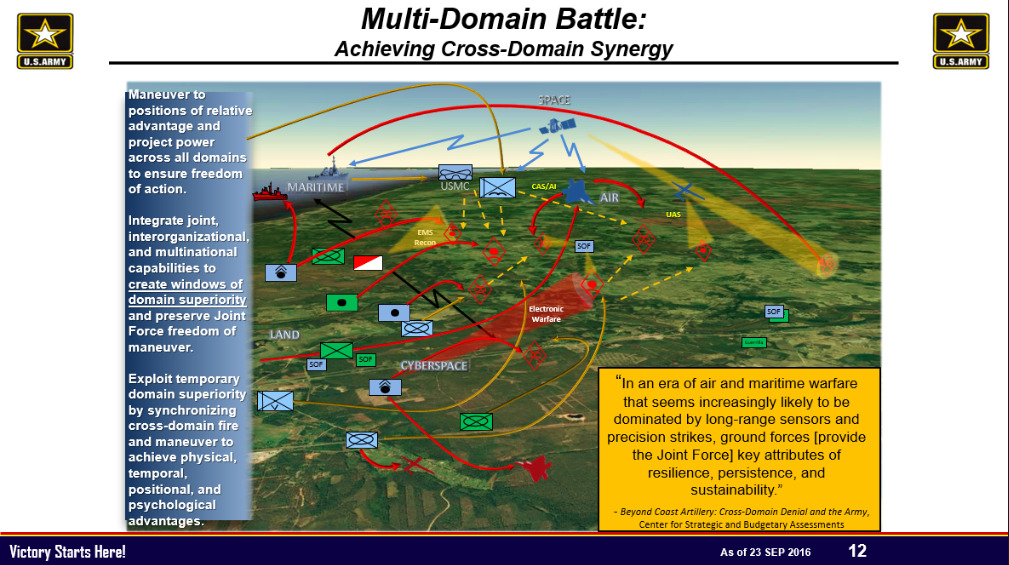

This armed recon role is particularly important against advanced adversaries like Russia or China, which deploy dense, multi-layered Anti-Access/Area Denial defenses. Since the range of precision missiles keeps getting longer, Army aircraft need to be based further from the front line to avoid being destroyed on the ground and penetrate deeper into enemy airspace to find enemy launch sites. That drives a requirement for longer range and higher speed than is physically possible with conventional helicopters, which in turn leads industry to offer either tiltrotors like the Bell V-22 and V-280 or compound helicopters like Sikorsky’s S-97 and SB>1. (Click here for an explanation of the difference).

Tracked variant of the Russian Pantsir S1 anti-aircraft missile system (NATO reporting name SA-22 Greyhound)

The solution to the Anti-Access/Area Denial problem can’t just be a new aircraft, however high-tech. The emerging Multi-Domain Operations concept calls for scout aircraft to work closely with long-range land-based missiles, for example. The missiles blow a hole in the enemy anti-aircraft defenses, the aircraft flow through and find more targets for the missiles. Repeat. In some cases, it may require ground forces like tanks and infantry to overrun enemy radars and SAM batteries before the aircraft can penetrate further — and those ground forces, in turn, need to work closely with scout aircraft to find hidden enemies.

From the limited materials available, Ostovich is uncertain whether the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft is devised with the broader complexities in mind. “I’m concerned that these requirements are being authorized by aviators — and I used to be chief of aviation so I’m not badmouthing aviators — but I’d much rather have these requirements be (also) driven by ground maneuver forces,” he told me. The armed scout role “is the small, light aircraft that’s integrated with the ground maneuver forces and those battalion and brigade commanders of infantry and armor.”

In the face of modern anti-aircraft threats, however, should we still be putting human beings in “small, light aircraft” flying close to the ground? “There’s a good argument made that this should be a mission for unmanned aircraft,” Ostovich said. But Army aviators believe “we’re not ready yet to replace the man in the equation.

“When you employ killing mechanisms, you’d like to have a human somewhere in that loop,” Ostovich said, and not in some distant bunker running the war by remote control but, “on the battlefield, with the curiosity that come from the human brain.”

The Army hopes to have the best of both worlds by requiring the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft be “optionally manned,” able to fly with humans aboard or without depending on the danger and complexity of the mission. One of the companies that’s done the most work on this kind of human-computer teamwork, incidentally, is Sikorsky, giving that company another leg up.

Timelines and Funding Lines

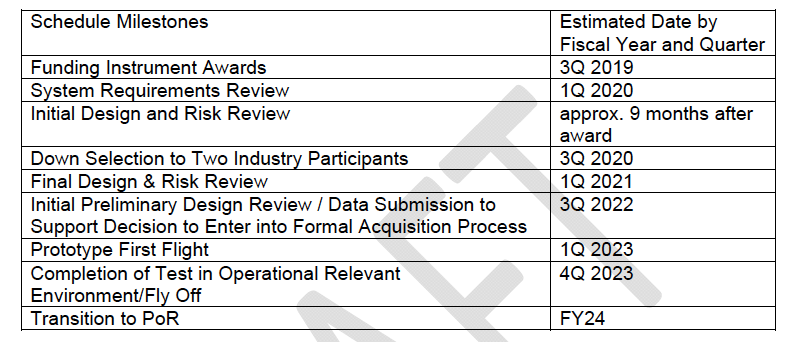

While the requirements and funding for the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft are as yet unclear, the Army’s timeline is remarkably precise:

- September 2018: Final version of the solicitation is published.

- December 2018: Proposals due.

- Approximately June 2019: Award “four to six” Other Transaction Authority For Prototype (OTAP) contracts for “initial designs”

- 2020: review system requirements, initial designs, and potential risks.

- Late 2020: Award two contracts to build actual prototypes.

- 2021-2021: further design and risk reviews

- 2023: prototypes fly and undergo “fly off” testing in an “operational[ly] relevant environment.”

- 2024: The Army “may” transition the winning prototype to an acquisition Program of Record. The document makes clear there’s no guarantee.

The Army will have a lot on its acquisition plate by the early 2020s, like a decision about buying robotic tanks, with no certainty about funding. The scout aircraft initiative is particularly complicated because it will affect the joint Future Vertical Lift effort, even if it’s not a formal part of it. That means the other services and, ultimately, the Office of the Secretary of Defense will have a major say.

If the Army wants a light armed scout before the mid-size transport that FVL is focused on, “that’s going to be a big-time OSD-level discussion,” one Army official told me. “I don’t think the Army has nailed down how we do the funding, because it’s not solely an Army decision.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.