Two Alternatives To The Bad Iran Deal

Posted on

The July nuclear deal concedes far too much to Iran and will increase its capacity to terrorize the Middle East and American interests and allies there.

There are at least two diplomatic alternatives to the July deal on Iranian nuclear activity.

We can stick with the interim agreement — just extend it — which is more restrictive than the Iran deal of July 14.

Or we can stay within the confines of the existing Non Proliferation Treaty (NPT) which Iran signed in February 1970. And we can add to that the required Additional Protocol (AP) to the NPT which Iran has continuously promised to uphold.

The current “deal” does not have to be a “take it or leave it” proposition. Negotiations on Iran’s nuclear activity have been undertaken now for nearly two decades, including a June 2006 and June 2008 comprehensive proposal to Iran from the United States and its P-5 partners which contained many of the current deal parameters.

Now there is a legitimate question of whether sticking to one alternative, such as the NPT and current sanctions regime would work better, rather than doing this new deal — which is essentially an interim 10- to 15-year “excursion” away from the NPT.

A couple of issues are in play, including Iran’s suspected military nuclear work and how one compels Iranian compliance with any deal, not just the new July agreement.

First, the 2006 UN Security Council resolution said Iran’s suspected nuclear work in at least 12 areas was military oriented and thus illegal under the NPT. The new deal does require Iran to “discuss” this with the IAEA and to come to a resolution thereof.

But in the final analysis Iran gets to allow the IAEA inspectors to visit and inspect only those sites it deems appropriate and in a manner it deems necessary. IAEA can reject Iran’s actions as inadequate in its report to the Board of Governors in December 2015.

But exerting pressure from the other side is a financial stampede going on now to approve the agreement and get possible business deals with Iran underway. This is further complicated by those arguing it makes no sense to try a different approach because it is claimed the only alternative to the July deal is war, not a better deal.

Second, and most importantly, knowing the exact extent of past Iranian secret military activity is critical for the deal to work. As proliferation expert Will Tobey explains in the July 16 Wall Street Journal you cannot judge how long it will take Iran to produce enough nuclear fuel—in a breakout– to build a small arsenal of nuclear weapons unless you know from where it is starting.

This has been at the core of all previous efforts to get Iran to come clean, including the diplomatic efforts of previous administrations, particularly that of George W. Bush. And as important as the history of these suspicious activities are — they never have been revealed by the Iranian government but have been brought to our attention by dissident groups within Iran and other intelligence services particularly that of Great Britain.

And third, without the ability to inspect future such sites and to quickly examine suspected military activity verification is not just less than perfect but highly inadequate. There are no anywhere, anytime inspections for future suspected activity.

Now central to all of this is whether one believes the threat of economic sanctions remaining in place or being re-imposed once removed will be sufficient to compel Iranian compliance with either the NPT, the interim agreement or the new July deal.

If sanctions were unraveling, as the administration claims, why would their re-imposition keep Iran from cheating either within the confines of the interim agreement, the NPT or the new deal? Sanctions already are the only enforcement mechanism for all three of these alternatives (if you exclude military force). If Iran knows the sanctions are going away, then what is their incentive to worry about them once they are gone?

Here lies the next strange contradiction. The sanctions adopted in 2011 against Iran did bite and they were serious. Access to the international banking system was cut off and oil revenue was basically impounded. They brought Iran to the table and did restrict Iran’s nuke program. And as a result the 2013 Interim Agreement was produced with restrictions greater than what are contained in the July deal. So why take away sanctions which were working?

Could it be that in their eagerness to get in on business opportunities in Iran, the P5+1 agreed to lift the sanctions much too quickly? The Russians wanted to sell Iran conventional weapons and nuclear energy technology; the Chinese wanted to buy more Iranian oil. And too many European and American firms were salivating at the prospect of doing business with 80 million Iranians.

Once we caved on sanctions going away only over time, there remains no other effective enforcement mechanism to make sure Iran stayed within the confines of the July agreement except military force.

Even worse, little noted is that any business deal completed prior to sanctions being re-applied — the snapback idea—are exempt from the affects of sanctions. That is a huge concession to Iran — one that is unnecessary if we went back to the NPT framework.

Thus a new deal opened up the door to new concessions which Iran was more than happy to accept.

As we have noted, critical to making sure Iran abides by any agreement is the ability to go beyond “declared” nuclear sites to make inspections. Yes, declared sites—those both sides agree are for nuclear activity– can be monitored. But that is not the sole worry–it’s the undeclared and covert, secret sites that really matter.

Here there is confusion as well. It is true under the July deal there is a 24-day period after which the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and Iran have to resolve disputes over inspection of such sites. But if Iran continues to refuse, Tehran can delay things up to another 75 days.

How? They force the UN Security Council to consider accepting snapback sanctions—which automatically occur with a finding made to the Security Council of a serious complaint filed with the council. There is nothing stopping Iran from repeatedly adopting such a “rope-a-dope” strategy to see whether sanctions will in fact be adopted every time Iran fails to comply with the July deal up to the 75-day period.

Also, the Security Council may not act to snap back sanctions unless violations by Iran are seen as significant and key to the new deal’s effectiveness. I am not sure how one figures that out, but that is what the deal says.

In short, Iran traded the removal of sanctions—what we are told was going to happen anyway—for the future right to enrich an unlimited amount of nuclear weapons fuel and become a full fledged virtual nuclear weapons state.

In the meantime, once Iran’s nuclear “activity” is found under a “Broad Conclusion” by the IAEA and its Board of Governors to be “peaceful”, or given a “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval” (which could occur as early as March 2016), Iran gets three goodies. There is: (1) an end to the missile and arms embargo on Iran; (2) an end to the sanctions involving Iran’s terrorist activity; and (3) a payment to Iran of $150 billion in escrowed oil revenue.

All of which enormously benefits Iran — not the United States.

As Michael Hayden (former director of both CIA and NSA) explains, Iran also keeps a very large industrial size nuclear capability intact under this deal. In the future, once the deal expires, Iran could break out of the deal and sprint to nuclear weapons status as it can make unlimited amounts of enriched bomb fuel.

How much better it would be to stay strictly within the confines of the NPT, and eliminate the current enrichment capability including the centrifuges in storage and those still enriching fuel?

Iran under the July agreement can supposedly succeed in a nuclear breakout only by securing enough nuclear fuel for a bomb in 12 months. This deal supporters claim is sufficient to allow the P5+1 to take appropriate action including using military force to stop any further proliferation.

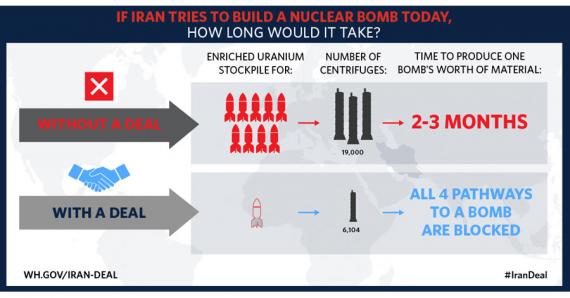

But Alan J. Kuperman, coordinator of the Nuclear Proliferation Prevention Program at the University of Texas, argues that the actual breakout time under an anticipated deal, is only three months — likely an insufficient span of time for the monitoring powers to detect and act against an Iranian breach of the deal. This is because Iran could use the 14,000 centrifuges in storage, not just the 6,000 allowed under the deal. And if they can produce a bomb using the same amount of nuclear material as Pakistan did in 1998, the breakout time is only three months.

The head of the IAEA, Director General Yukiya Amano, has said the fact that Iran will have to implement the Additional Protocol will require Iran to allow IAEA inspectors to visit all suspicious non-nuclear sites. True, but the process to get such inspections could be drawn out by 100 days if you include the time needed for the UN to re-impose sanctions to compel Iranian compliance.

If Iran, sometime in the future, has accelerated its research on enrichment, received its $100 billion dollars, secured conventional arms and missile components with which to threaten and terrorize its neighbors, then a three-month breakout may indeed be precisely the time Tehran and the mullahs need to display its nuclear capability by producing a nuclear bomb.

Then what?

Peter Huessy, president of defense consulting firm GeoStrategic Analysis, is an expert on international nuclear issues and organizes the Congressional Breakfast Seminar series for the Air Force Association.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.