Trump Won; Four Global Realities He Faces

Posted on

Americans woke up on November 9 with a collective sigh of relief: the election was finally over. Now, we get to the hard part: filling appointments in the executive branch, passing legislation, and getting the federal government to work again.

The period between Election Day and January 20 is a great time for a refresher course on the state of world today and what the next administration must do to ensure that the U.S. can juggle the equally important tasks of keeping this country secure and not overextending America’s diplomatic, economic, and military resources. Here are four realities that soon-to-be President Donald Trump will need to come to terms with.

North Korea is already a nuclear weapons state: The next administration no longer has the luxury of demanding denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula and pretending that Pyongyang is not a nuclear weapons power. The sad reality is that Kim Jong-un is not going to trade his weapons away; denuclearization without a major confrontation is not likely on the table. Whether Washington wants to acknowledge it or not, North Korea is in the nuclear weapons club.

U.S. policy on the North Korean nuclear file hasn’t changed for three decades, even as Pyongyang’s nuclear stockpile has grown, its ballistic missile program has accelerated, and the Kim dynasty has gotten bolder about building a nuclear deterrent. Notwithstanding the pile of economic sanctions imposed on the country, the vastly improved defense and intelligence cooperation between the U.S., South Korea, and Japan — and the introduction of the most advanced anti-missile system in the world today — North Korea continues to go its merry way towards a nuclear delivery system that is effective enough to reach the continental United States.

U.S. policy on the North Korean nuclear file hasn’t changed for three decades, even as Pyongyang’s nuclear stockpile has grown, its ballistic missile program has accelerated, and the Kim dynasty has gotten bolder about building a nuclear deterrent. Notwithstanding the pile of economic sanctions imposed on the country, the vastly improved defense and intelligence cooperation between the U.S., South Korea, and Japan — and the introduction of the most advanced anti-missile system in the world today — North Korea continues to go its merry way towards a nuclear delivery system that is effective enough to reach the continental United States.

Syria’s Assad is likely to stay in power: Donald Trump argued throughout his campaign that he would be open to creating humanitarian corridors or safe zones within Syria as long as the Gulf States paid for them and led the operations with their own soldiers. That same safe zone option was a nonstarter for the Obama White House — a policy that, in the opinion of former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin Dempsey, would force commanders to pull vital military resources from other theaters and require “hundreds of ground and sea-based aircraft, intelligence and electronic warfare support, and enablers for refueling and communications” at a tune of $1 billion per month. If the U.S. military is unwilling to assist the operation in some way, it’s tough to see America’s Arab partners making the leap and performing a task that would cost billions of dollars and likely result in some casualties among their soldiers.

The Trump administration will enter office with no good options on Syria. The establishment of safe zones would more than likely require U.S. involvement in the air to entice Arab states like Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Turkey to participate. More planes in the air naturally means a greater chance of confrontation with Russian pilots who have dominated Syria’s airspace for over a year. Syria, to say the least, isn’t worth getting into a shooting war with the Russians, and it’s not something that a President Donald Trump would be keen on doing given his stated intentions to improve Washington’s relationship with Moscow during the first few months of his presidency. (The editor notes that the Obama administration made very similar noises about Russia at the beginning of its administration.)

Unless the next administration is willing to use overwhelming force over a long period of time, Assad will remain in the presidential palace. The best formula that we can hope for is far less than what we originally wanted: a deal that allows Syrians to vote for a new president at an earlier date than 2021 —monitored by U.N. observers who have the freedom to move around and certify the results — in exchange for Assad running as a candidate. It may be one of the only proposals that the Russians and Iranians could accept.

Iraq is too dependent on the U.S.: The military campaign against the Islamic State has been going well over the past year, so well in fact that U.S. officials are scrambling to determine what kind of politics will be left behind to govern Mosul once the massive Iraqi-led invasion force inevitably recaptured the crown jewel of the group’s dwindling caliphate.

Taking the results on the battlefield in isolation, it would appear that the Iraqi army — that same national force that folded two years ago in one of worst humiliations for Baghdad since the 2003 invasion of Iraq — is far more professional. Fallujah, Ramadi, Baiji, Tikrit, Rutba, and Sinjar have all been recaptured by the Iraqi security forces over the last year, and Mosul will be added to that list in a few months time. Yet what often gets overlooked is the principal reason Daesh (aka ISIL) has been forced into smaller and smaller amounts of territory: the U.S. Air Force.

U.S. pilots have conducted tens of thousands of airstrikes on behalf of Baghdad. In Ramadi, an operation that took longer than many expected, the Iraqi army was only able to win the city after much of it was leveled by coalition air power In the ongoing operation for Mosul, U.S. jets are shaping the battlefield by taking out car bomb factories, ISIL checkpoints, leadership, and ammunition dumps to ease the Iraqis’ path. During the first two weeks of the Mosul offensive, the United States bombed or shelled ISIL positions more than 3,000 times, a huge amount of precision fire for a campaign that the Obama administration continues to insist is led and directed by the Iraqi security forces.

Combining coalition air power with local ground forces is, of course, the core of the counter-Daesh strategy, and the last year has demonstrated that this combination is depriving these terrorists of territory. However, it also exposes the extent to which Baghdad leans on the U.S. Air Force to make any gains on the ground at all. And then there is the probability that Iraq’s sectarian and ethnic groups — many of which have no shared interests other than destroying Daesh— could turn their guns on each other once the terrorist group is crushed. Is President Trump willing to expend U.S. diplomatic and military resources toward ensuring that a new civil war in Iraq doesn’t erupt as soon as Daesh is driven from the battlefield? What resources would be required? For how long? And how long would a peace enforcement mission last?

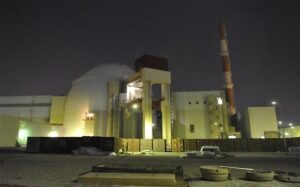

On nukes at least, Iran is cooperating: The Iranians are unhelpful and antagonistic in a lot of ways. Along with Russia, Tehran has: airlifted subsidized oil, ammunition, and intelligence support to Assad’s regime; deployed Quds Force operatives and sent Iranian generals to the front lines to coordinate Syrian regime offenses against opposition-held areas; sent weapons, including anti-ship missiles, to the Houthis in Yemen; and, increasingly, has dared U.S. sailors in the Persian Gulf to engage them at sea.

On nukes at least, Iran is cooperating: The Iranians are unhelpful and antagonistic in a lot of ways. Along with Russia, Tehran has: airlifted subsidized oil, ammunition, and intelligence support to Assad’s regime; deployed Quds Force operatives and sent Iranian generals to the front lines to coordinate Syrian regime offenses against opposition-held areas; sent weapons, including anti-ship missiles, to the Houthis in Yemen; and, increasingly, has dared U.S. sailors in the Persian Gulf to engage them at sea.

Importantly, Iran has also met the commitments it signed up to in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. In multiple reports that the IAEA has released throughout the first 10 months of the agreement, the agency has verified that Iranian scientists are permitting inspectors to access their uranium enrichment and centrifuge production facilities, have kept their in-country stockpile of low enriched uranium under 300 kg, and have quickly addressed any violations or problems with the Joint Commission that is responsible for monitoring the deal’s progress. The assumption that Iran would pocket the sanctions relief and quickly violate the agreement fortunately hasn’t come to pass.

That being said, the Iranians have violated the agreement on the margins on several occasions. Heavy water production, which is nominally capped at 130 metric tons, has at times exceeded those limits and forced the IAEA Director General to note his concerns in the agency’s quarterly reports. Earlier this year, Tehran attempted to purchase carbon fiber from Germany, a dual-purpose item that could be used in producing advanced rotors for centrifuges. And several Iranian entities that were previously sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council for attempting to purchase nuclear-related material for the Iranians are now reportedly trying to do the same thing in China now that they have been delisted under the agreement.

The Trump administration pledges to scrupulously ensure that Tehran isn’t cutting any corners, promising that if they are caught, internationally imposed economic sanctions will be reimposed. President Trump will need to come to a series of conclusions internally as to what kinds of Iranian violations warrant a full-scale return of the sanctions and which are minor enough to be addressed through diplomatic channels at the Joint Commission.

Donald Trump has never led or managed a bureaucracy as large as the U.S. government before. He possesses less foreign policy experience than almost any other president, a fact that could cause him trouble when an international crisis hits — particularly if he doesn’t assemble a steady and knowledgeable team around him. Like all presidents, Trump will have a tremendous amount of work to do during his first 100 days. Understanding the world as it is, rather than buying into the conventional Washington wisdom, will help ease what is bound to be the most difficult job on the planet.

Daniel DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities, a thinktank.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.