Trump’s Generals, Part 4: John Kelly vs. The Narco-Terrorists

Posted on

Then-Maj. Gen. John Kelly in Anbar Province, Iraq. (From a video commemorating his retirement)

Who are Trump’s generals? This week, James Kitfield has already told us about James Mattis and Michael Flynn, both men shaped by the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Now we come to John Kelly, whose time in Latin America, ironically, led him to similar conclusions about America’s enemies.

As chief of US Southern Command, General John Kelly spent much of his time worrying about the nexus of violent drug cartels, transnational smuggling organizations, and terrorist groups in Latin America. The threats range from narco-Marxists like Colombia’s FARC and Shining Path in Peru all the way to Hezbollah, which has a presence in the region due to a large Lebanese diaspora. All of those groups ply their trade near a porous US southern border.

Gen. John Kelly

“There have been notable successes in this region, such as Colombia’s fight against FARC, but I continue to be concerned about this convergence between known terrorist organizations and illicit smuggling and money-laundering networks,” Kelly told me in an interview last year, before he retired. “There are those in the intelligence community who take the view that it is not a major threat and argue that those groups will never find common cause. I think those who take that view are simply trying to rationalize away the problem because no one wants to raise another major threat at a time when we face so many around the world.”

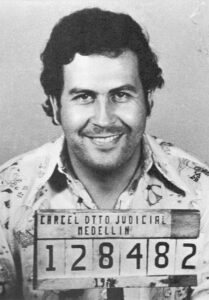

The hybrid threat of “narcoterrorism” is not new. In the 1990s, the US joined in Colombia’s fight against Pablo Escobar’s Medellín cartel, a hyper-violent criminal organization that turned to terror in its fight against Colombian authorities, routinely bombing police buildings, assassinating judges and politicians, and even blowing up a civilian airliner in flight.

Pablo Escobar

With US help, Colombia successfully fractured the Medellín and Cali cartels in the 1990s — but this victory had the unintended consequence of creating a vacuum in the lucrative drug trade. That vacuum was eventually filled by brutal Mexican cartels and Colombia’s FARC, which morphed from a Marxist insurgency relying on terrorist tactics into primarily a drug production and trafficking organization. According to Drug Enforcement Administration statistics, nearly 40 percent of the State Department’s designated terrorist groups are now involved in drug trafficking. Like bank robbers in the roaring ’20s, today’s terrorists are just going where the money is.

The connective tissue between terrorists, drug cartels and smuggling networks makes narcoterrorism a potent threat. For instance, in 2011, an Iranian operative named Mansour Arbabsiar approached an extremely violent Mexican drug cartel with a murder-for-hire proposal. Arbabsiar was working for the Iranian military, and he proposed that a cartel hit man assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the United States — not with a sniper’s single bullet, but by bombing a popular restaurant in Washington, D.C., that the ambassador frequented. Luckily, and only by chance, the individual Arbabsiar approached was a DEA informant, and the plot was thwarted.

In another instance the same year, DEA agents in Guatemala intercepted a shipment of cocaine and $20 million tied to the Mexican cartel Los Zetas. In a wide-ranging conspiracy investigation, the DEA discovered that the drug shipment was part of a smuggling network that moved product from South America to Europe via West Africa. The profits were then laundered through the Lebanese Canadian Bank, which scrubbed the money in part by financing a string of used-car dealerships in the United States. The ultimate benefactor of the proceeds? The Iranian-backed Lebanese terrorist group Hezbollah. The US Treasury Department ultimately shut down the Lebanese Canadian Bank, exposing its links to Hezbollah and sanctioning it under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act.

Gen. John Kelly with Gen. Joseph Dunford, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

An ‘Existential’ Threat

Near the time of his retirement as commander of SOUTHCOM last year, Kelly made headlines by calling the confluence of terrorism, violent drug cartels, collapsing societies and out-of-control migration an “existential” threat to the United States. As Trump’s choice to lead the Department of Homeland Security, he can be expected to take seriously the task of securing the southern US border and increasing the intelligence and law enforcement resources devoted to countering the narcoterrorism threat.

Coast Guard Commandant Adm. Paul Zukunft (right) meets with then-Southern Command chief Gen. John Kelly, now Trump’s nominee for Secretary of Homeland Security.

“I’m paid to worry about worst-case scenarios, but to me if a known terrorist group is doing business with a known illicit smuggling network, that amounts to convergence, and we’re already seeing it,” Kelly told me last year. The organizations may not share the same motives or ideology, he noted, but illicit smuggling networks don’t check passports or do baggage checks, and they involve thousands of unscrupulous subcontractors who are interested in money, not motive.

“So if we don’t care about a heroin epidemic or illicit drugs from Latin America that kill 40,000 Americans on average each year, or the fact that these cartels are corrupting and intimidating the governments of our neighbors with illicit money and violence, then we should at least care about these brutally efficient smuggling networks that reach deep inside the United States,” Kelly said. “ISIS often talks about that vulnerability on their websites.”

This story concludes our series on Trump’s generals. Click back to read the profiles of Jim Mattis and Mike Flynn, or read the introduction about what Trump’s generals have in common as a group.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.