Trump’s Claim Of $2.5 Trillion In DoD Dough: Not True

Posted on

FORT MYER: “We’ve spent $2.5 trillion since I’m president — $2.5 trillion, far more than this country has ever even thought about spending,” President Trump said here yesterday. “When I took over, we were a very depleted military, and today, we’re at a level we’ve never even come close to.”

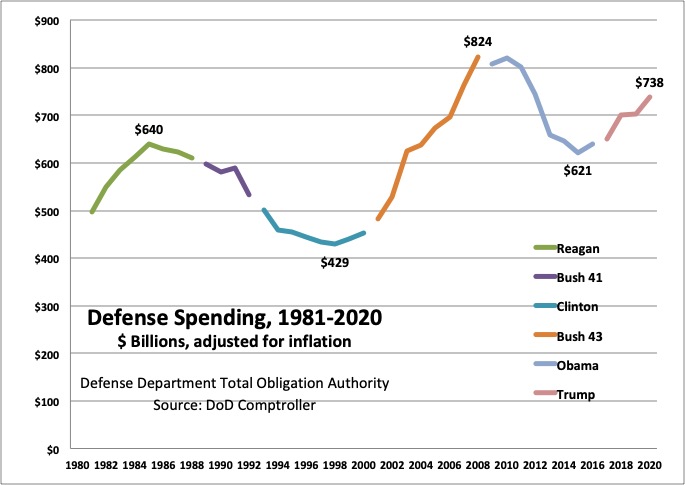

Is that true? Well… Trump definitely has driven a sharp buildup in defense spending after years of steep and painful cuts under Obama. But today’s spending levels are hardly unprecedented — and you don’t have to go back to the Cold War or World War II for a comparison, just seven years. Adjusted for inflation, both George W. Bush and Obama spent more each year from 2007 though 2012.

What about the actual end result — how much security does that money buy? Yes, combat readiness has recovered from its sequestration-induced nadir in 2013. But the Pentagon and independent experts alike fear the US is losing its technological and strategic edge over Russia and China.

Breaking Defense graphic from Defense Department Comptroller & Congressional 2020 budget deal data

The $2.5 Trillion Solution

Start with that $2.5 trillion figure. Trump touted it both yesterday, at the official installation of Gen. Mark Milley as the new Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and last month, during his speech to the United Nations.

Todd Harrison

“If you count FY [fiscal year] ’17—which started while President Obama was still in office—then you can get to $2 trillion, but not $2.5 trillion,” CSIS budget expert Todd Harrison told me. “I think President Trump must be including FY20 funding to get to the numbers he’s talking about, but FY20 hasn’t started yet, so that funding has not been ‘spent’ in any sense of the word.”

“To be fair to Trump,” added fellow CSIS budget guru Mark Cancian, “he has continued and accelerated a defense buildup that began in FY 2016, even if it does not qualify as ‘the largest in a generation.'” (The “largest in a generation” claim comes from Vice-President Pence’s speech yesterday).

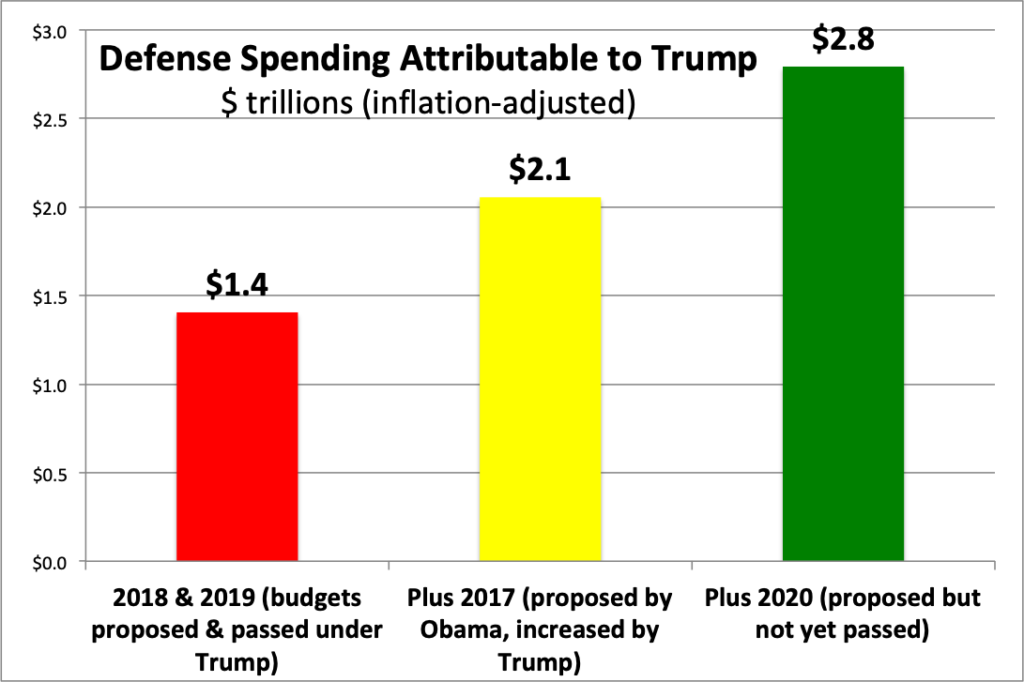

If you want to take as strict a stance as possible, you’d only give Trump credit for the budgets that his administration proposed and that Congress has actually passed. By that standard, you’d only count 2018 and 2019: 2017 was proposed under Obama, 2020 hasn’t passed yet. Using the Defense Department Comptroller’s official inflation-adjusted figures, those two years total $1.4 trillion.

But the 2017 budget was passed after Trump took office. And he didn’t just inherit Obama’s work. He had a substantial impact on the final figure, convincing Congress to pass a supplemental appropriation increasing defense spending by $15 billion.

“I would include the first budget the administration could affect. For Trump that would be FY 2017,” Cancian told me. “Plus, Trump was president for about 70 percent of that fiscal year, so to call it an Obama year, for defense, deficits or anything else, would be misleading.”

Mark Cancian

So it would be entirely reasonable to give Trump credit for all three years of defense spending, 2017-2019, a total of $2.1 trillion.

What about 2020? It definitely hasn’t been “spent” yet. It hasn’t even been passed. In fact, it may never pass. Gridlock between the Democratic-controlled House and the Republican-controlled Senate — especially over Trump’s taking Pentagon funds to pay for his border wall — still could force a year-long Continuing Resolution, which would continue spending basically on autopilot at 2019 levels.

But the House and Senate did agree on an overall budget framework that allows $738 billion for defense. So while Trump can’t claim this money as “spent” — and indeed it takes years for the Pentagon to actually pay out all the funds appropriated for it in a given fiscal year — he’s not being irrationally optimistic in expecting it will be.

If you count all four years, 2017-2020, then the total amount that either has been spent under Trump or will be spent comes to $2.79 billion. That’s actually 12 percent more than the president’s $2.5 trillion talking point.

Breaking Defense graphic from Defense Department Comptroller Data

Impressive? Yes. Unprecedented? No. Enough? Perhaps

Trump can take pride in getting a divided Congress to agree to spend $738 billion on defense next year, even if the deal is not final. But his claim to have outspent previous administrations is not true. Comparing inflation-adjusted dollars, the government spent more on defense every year from 2007 through 2012. That period covers both the peak of the war in Iraq, Bush’s 2008 “surge,” and Obama’s dual-pronged policy of withdrawing from Iraq and surging in Afghanistan.

The dramatic plunge comes in 2013, and it’s not just Obama’s doing. Both parties in Congress agreed to the 2011 Budget Control Act (colloquially known as sequestration when it took effect) that — when the parties couldn’t agree on specific reductions in spending — imposed automatic across-the-board cuts in 2013, using an obscure fiscal mechanism known as sequestration. Every cabinet department was affected, including defense, which had to precipitously cancel military training exercises and postpone major maintenance to pay the bill. The impact was painful, with some experts drawing a direct line from cancelled training flights in 2013 to fatal crashes in later years.

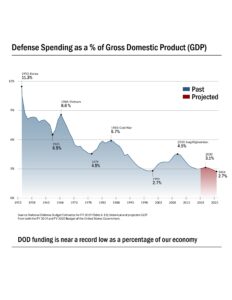

US defense spending as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product since the Korean War (DoD graphic)

The Army has dramatically improved its readiness since, going from just two brigades deemed combat-ready to 28, as Trump trumpeted yesterday. The Navy fighter fleet has met an ambitious goal of having 80 percent of its aircraft rated mission-capable. But readiness rates for many Air Force fighters have actually gone down, while the Navy’s warships are still plagued by maintenance backlogs.

Now, military readiness — the ability to “fight tonight” — is only part of the strategic equation. The other is modernization — the ability to fight in the future. Research, development, and procurement of new equipment definitely suffered as the Pentagon struggled to come in under the Budget Control Act caps. (The BCA expires at the end of 2020, which is not a Trump achievement but an escape mechanism built into the original 2011 bill). And Trump has definitely driven significant increases, with the Army, Air Force, and Navy all rapidly introducing cutting-edge technology like hypersonic missiles.

Does that mean “America’s armed forces are more powerful than ever and growing even stronger,” as Trump declared yesterday at Fort Myer? Well, no. While it’s true — almost by definition — that today’s military has some technology that’s more advanced than anything in the past, much of its hardware is still aging, albeit-much-upgraded, materiel first purchased during the Reagan era. And the military is smaller than it was at the height of the Iraq War, let alone the Cold War. It’s been at roughly 1.3 million regular active-duty uniformed personnel for years, significantly below the 1.4 million figure from the peak of the surge.

But military power is meaningless in a vacuum. What matters is relative power compared to potential adversaries — and that is something the Pentagon’s increasingly anxious about, as we’ve reported for years.

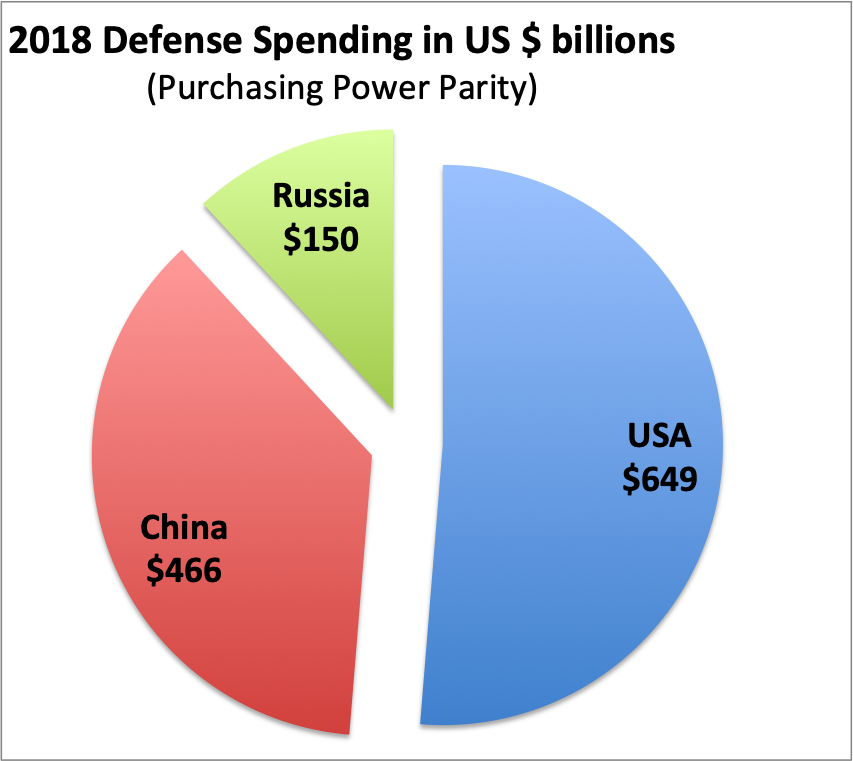

Breaking Defense graphic from World Bank PPP conversion rates & Stockholm International Peace Research Institute spending estimates

Russia & China

The US military remains, as Trump and every other leading official says, the most powerful on the planet. Traditional comparisons say the US defense budget exceeds the next seven largest countries’ combined. But those comparisons convert rubles, yuan, and other currencies into dollars at standard international exchange rates. That accurately reflects how many imports a country can buy — but Russia and China build the vast majority of their defense equipment themselves and pay for it in their own currency. If you compare domestic buying power, aka Purchasing Power Parity, then Russia and China combined spent 95 percent of what the US did in 2018. And China’s spending is rising fast and most of the weapons they are building are brand new. Also, their personnel and health care costs are substantially lower than America’s.

Approximate ranges in miles from Chinese territory to select US and allied targets. Credit: Google Maps

Equally important as total spending, moreover, is how that money’s spent. Russia, Iran, North Korea, and, above all, China have invested heavily in forces specifically designed to counter US strengths and exploit their home-field advantage. The areas they seek to dominate, from Ukraine to Taiwan, are much closer to them than they are to the United States, and US forces based abroad are much reduced from the Cold War. Russia and China don’t have to beat the entire US military to achieve their objectives. They just have to defeat or bypass the forces they confront and then consolidate their position enough that a US counter-offensive looks prohibitively costly.

Trying to deter, forestall, or roll back this kind of blitzkrieg land-grab is driving the US military to develop new concepts for combat. Concepts matter: In both historical wars and in the Army’s latest wargames, using old equipment in new ways is often more powerful than using new equipment in old ways. But ultimately, ambitious new approaches such as Multi-Domain Operations — the idea of synergizing US strengths across land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace as never before — still require the right hardware to implement. And that’s expensive.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.