Trench Warfare With Wings: Can ISIL Airstrikes Go Beyond Attrition?

Posted on

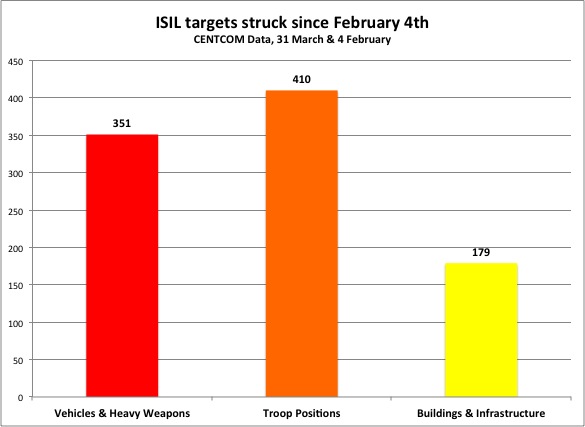

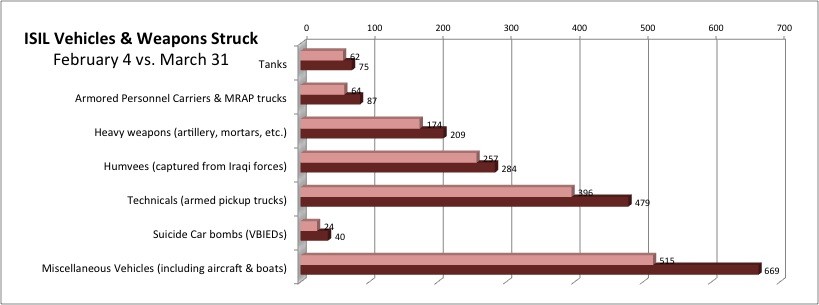

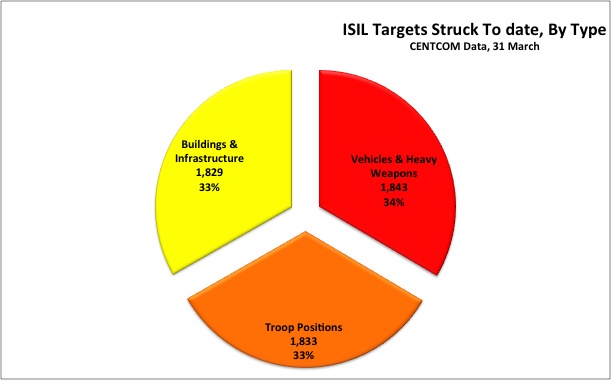

Airpower sounds swift and surgical, but sometimes it’s really closer to trench warfare with wings. Earlier this week, with the smoke still rising from the retaken Iraqi city of Tikrit, Central Command released detailed data on air strikes against the self-proclaimed Islamic State. We’ve crunched the numbers, and it’s clear the eight-month-old campaign is becoming a war of attrition.

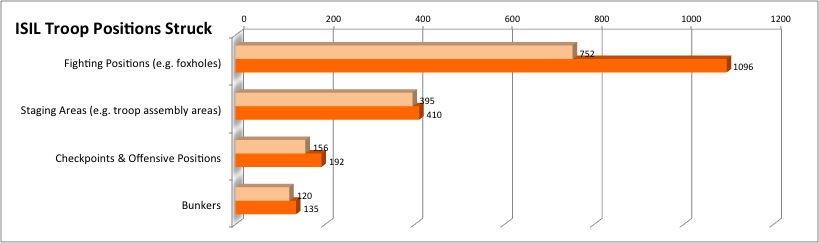

The airstrikes are grinding away ISIL one truck or frontline unit at a time, focusing on close support to Iraqi forces. (Although Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Welsh was careful to tell my colleague Colin yesterday that the F-22s operating in the region have not executed any Close Air Support missions. For that matter, no one has referred to any strikes in either Iraq or Syria as CAS missions.)

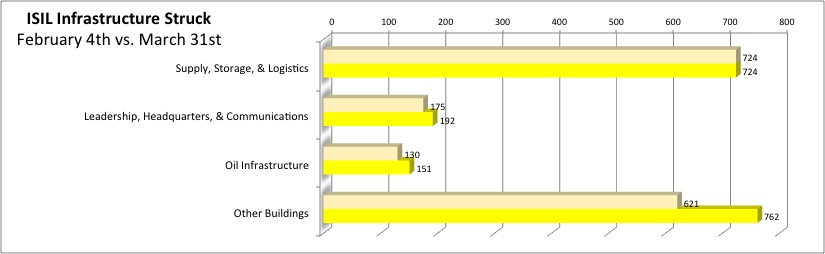

Meanwhile, compared to figures released just on February 4th, there’s a decreasing emphasis on more strategic targets such as enemy leadership or oil revenue. In fact, oil infrastructure represents just 151 of 5,457 targets reported hit, less than 3 percent.

You might think that a jumped-up terrorist group like ISIL wouldn’t have too many strategic targets to strike in the first place. But leading airpower expert and Breaking Defense Board of Contributors member David Deptula, a retired Air Force three-star, argues the US is missing an opportunity to use its airpower to greater effect.

“Too many people are falling into the trap of, ‘well, y’know this isn’t an industrial power,'” Deptula told me. “They might not have the same number of oil refineries as in Ploesti” — the famed Romanian oilfield targeted by US bombers in 1943 — “but that’s in fact where they’re getting their money from: the oil fields in Syria.”

This is not a counterinsurgency, Deptula said, but a war against a would-be state with a complex organizational structure. “Do not be sucked into fighting the last war,” he said. “This is part of the problem. You have leaders who are putting together the Operation Inherent Resolve plan whose only experience has been 10 years of hunting down HVIs [High Value Individuals] in Iraq and Afghanistan; this is a different challenge….You need to paralyze the ISIL leadership, their command and control elements.”

Yet most airstrikes into Syria have focused on the frontline around Kobani, not on ISIL leadership and infrastructure, Deptula said. Likewise, the US has not cut the terrorists’ long line of communication across the desert. “Why is the road between Raqqa [the ISIL ‘capital,’ in Syria] and Mosul, for example, still open?” he asked. “Why is electricity not terminated” in either city?

Wouldn’t shutting down the electrical grid harm the local civilian population? Yes, Deptula said, but not to an extent that would violate the laws of war. “This is one of the problems, there’s been more attention to the avoidance of collateral damage and civilian casualties than there has been to the accomplishment of eliminating ISIL,” he said. In fact, he argued — in an echo of long-ago airpower theorist Giulio Douhet — that bringing the war home to ISIL-controlled populations might turn them against their occupiers.

“What is the population of Mosul relative to the number of ISIL [fighters]?” Deptula asked, focusing on the city that’s likely to be the next decisive battle. “At some point, the population needs to be effected to the point that they will rise up themselves and rid themselves of this cancer.”

A leading land war analyst was skeptical of some of Deptula’s reasoning. “Yeah, you could take out power generation and other stuff,” RAND scholar and David Johnson told me, “[but then] you’ve just declared war on everyone in Mosul.” That’s about 1.5 million people, he said, some of whom admittedly hate us and the Iraqi government already, in a country where every adult male seems to have access to weapons.

“It took close to a month to go through Tikrit,” said Johnson, a former top advisor to Army Chief of Staff Ray Odierno, and the Iraqi forces rubbled much of the city in the process. “Mosul’s a much bigger city with a much bigger population,” he warned. The city’s layout is significantly denser as well, making it easier for ISIL to defend and harder for airstrikes to find targets. Johnson has no confidence that the Iraqi forces — a mix of uniformed regulars with US advisors and Shia militias with Iranian ones — have the discipline or tactical skill to take the city without flattening it, however precise the US airpower supporting them may be.

Could US airpower get more bang for its buck by targeting ISIL’s leadership, say, back in Syria? We can and have killed some of them, Johnson said, but many of these men are veterans of guerrilla warfare in Iraq. “They’ve been around American airpower for a while now and they’re taking measures to protect themselves,” he said. The dumb ones died a long time ago, back when there were more US aircraft around to bomb them and, just as important, vastly more US ground troops to find them and flush them out.

“It seems like they’ve got a fairly distributed operation that’s tightly disciplined,” but not centralized, Johnson said. The classic theory behind “decapitation” airstrikes is “cut off the head and the snake dies,” he said, but in the case of ISIL, “is it just one head?… I don’t know the answer to that.”

Unless we can figure out such a vital point to strike, we’re probably going to be stuck with airborne attrition for a long, long time.

Note: Totals through February 4th do not always equal the figures from our original article on the Feb. 4 data because CENTCOM changed some of its reporting categories, most notably by adding aircraft while omitting “ISIL controlled Bridges/highways,” “misc. equipment, ” and “training camps”; we worked with CENTCOM to ensure we had the best apples-to-apples comparison possible.

Colin Clark contributed to this story.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.