The US Needs A ‘Coast Guard’ For Space: Semper Paratus Exteriores Spatium

Posted on

Lonely duty in the far reaches of, well, not space, but the Arctic.

A battle has been underway for several years now over who will become the FAA of space and how they will do the job. Some wanted the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Tranportation, which boasts the great acronym, FAST. Some wanted NOAA or NASA. Most did not want the Air Force, which has had a difficult time building useful space situational awareness data gathering and analysis tools.

The following op-ed, which offers readers the wondrous vision of a Coast Guard in space, makes intriguing and sometimes compelling arguments for what the new entity should look like and offers lessons from the long history of the Coast Guard. The author is a Coastie commander with a law degree. He’s heading to especially hazardous duty as legislative counsel for the service. Read on! The Editor.

America needs an organization in outer space modelled after the Coast Guard to establish and maintain governance, address widening authorities and capabilities gaps, and better meet our international legal obligations.

A nascent space boom, one led by private actors and businesses, makes it more and more likely that existing international legal regimes will prove inadequate governance structures as increasing numbers of state and private actors take to the stars. Notwithstanding the House of Representatives’ recently passed legislation, the American Space Commerce Free Enterprise Act, the United States government currently divides responsibility and authorities for space operations amongst several departments and agencies, which is burdensome, inefficient and unlikely to be agile enough to keep pace with, let alone effectively regulate and manage, private space ventures.

The current process where the U.S. government oversees and regulates the commercial space industry is both too complex and not robust enough. As a result, the United States has the worst of both worlds. The existing space regulatory scheme does not encourage innovation because it is cumbersome and unwieldy. It also does not serve as an effective check on commercial space, which pursuant to international law is subject to the U.S. government’s “continuous supervision.”

The House legislation seeks to improve on the status quo. Currently, the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation, the Department of Commerce’s Office of Space Commerce, NASA, and in some cases NOAA and the Air Force all have roles to play in regulating, assisting or providing oversight for U.S. commercial space launches or activities. The House’s solution to this problem is to create a “one stop shop” in the Department of Commerce to regulate commercial space activities. Congress is correct to try to fix this byzantine process. It simply chose the wrong method.

Instead, America would be better served by consolidating all commercial launch-to-orbit-to-landing oversight and regulatory functions within the “prevention” arm of a new “Space Guard.” A Space Guard, initially conceived of by Cynthia McKinley in 2000 and later expounded on by James Bennett in 2011, should optimally mirror the organizational structure of the Coast Guard, which generally separates its mission functions into broad categories of “prevention” and “response.” Prevention authorities are essentially regulatory authorities and response authorities are best categorized as operational authorities.

Yet, despite this separation, Coast Guard prevention and response officers can, and often do, rely on overlapping and mutually supportive sources of authority to execute their respective missions. As noted in the Coast Guard’s foundational document, Publication 1, the Coast Guard’s broad authority to act and “[t]he interrelated nature of the Coast Guard’s missions and culture of adaptability provides the Service with the ability to rapidly shift from one mission to another as national priorities demand” across the entirety of the maritime domain. It excels at protecting those on the sea, protecting the nation against all threats and hazards delivered by the sea, and protecting the sea itself and it is in part the interdependent nature of these authorities that makes the Coast Guard so effective.

Nearly every authority that the United States needs for effective maritime governance is vested within the Coast Guard and the service’s 11 statutory missions cover the full panoply of possible action within the entire maritime domain. This means that the Coast Guard is the lead U.S. federal agency for nearly every matter that takes place within the navigable waters of the United States or that pertains to U.S. vessels or vessels in which the United States may exert jurisdiction. The agency also has wide ranging authority to coordinate and cooperate with other Federal and state agencies and foreign governments, conducts maritime mobility operations like ice-breaking and aid-to-navigation placement and maintenance, and quintessentially can perform any and all acts necessary to rescue and aid persons and protect and save property on and under the high seas and on and under water over with the United States has jurisdiction. All of these authorities translate in the context of space governance.

Applying this construct to a similarly organized and empowered Space Guard would thus result in a concentration of total domain expertise within one agency, which would lower regulatory cost burdens on the U.S. private space industry. At the same time, it would also likely lead to synergistic increases in mission effectiveness and efficiency by the regulators, who would be able to better leverage expertise from a common pool of experienced operators and scarce technical specialists all of whom would be able to coordinate more closely within the same organizational entity.

Presumably an enhanced Office of Space Commerce with new powers granted to it by the House legislation may share some of these benefits, but for a space governance agency to be truly effective, its prevention mission must be supported by response authorities and capabilities. For instance, take the pressing issue of space debris mitigation. Space scholars and commentators sometimes frame the proliferation of “space junk” as an environmental issue. There are certainly environmental concerns related to the use of space, but space debris mitigation is better categorized as a domain mobility issue because its true impact is to those who wish to use, navigate, and operate within space, not to space itself.

Before delving too deeply into space debris mitigation as a mobility issue, it is worth noting that the Outer Space Treaty (OST) does require states to ensure that government and non-state space farers avoid both the “harmful contamination” of space, including celestial bodies, as well as harmful contamination of Earth from space. These “planetary protection” aspects of the OST look a lot like the foundational basis behind the Coast Guard’s maritime environmental protection statutes and regulations, which themselves may provide a helpful model with which to base planetary domestic protection statutes. This is important, because currently there is no agency in the United States which has the authority to develop and enforce a planetary protection regime for either the U.S. government or the U.S. space industry. In contrast in the maritime domain, Coast Guard Captains of the Port have the authority to exercise plenary control over vessel movements within their respective zones for a wide variety of purposes, including environmental compliance. They also serve as the federal-on-scene coordinator for maritime environmental responses within those zones.

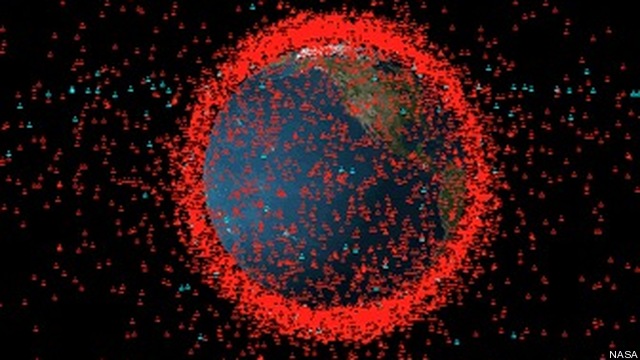

Space debris in orbit around Earth

The Coast Guard also uses marine inspectors to inspect commercial vessels within its jurisdiction to ensure regulatory compliance across the full spectrum of maritime activity from safety to environmental and a fleet of cutters and small boats to deliver boarding officers at sea to enforce an equally robust set of regulatory requirements for those vessels that fall outside the normal reach of the inspectors.

As for space debris management, it is perhaps helpful to start with the need to better establish space domain awareness (“SDA”). Right now, NORAD conducts the bulk of U.S. SDA and should continue doing so. But authorizing and then concentrating a parallel, and if necessary over-lapping SDA mission with a specific focus of space debris tracking as a Space Guard function would no doubt allow space debris avoidance and mitigation information to flow more easily to commercial space entities, thereby increasing the safety of their operations in critical space environments like Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and Geo-stationary Orbit (GEO).

SDA is a means, not an end in of itself, and as such the Space Guard should also be authorized, staffed and equipped to engage in space mobility operations analogous to Coast Guard maritime mobility operations—establishing and maintaining aids-to-navigation to help commercial, and frankly all space operators navigate through hazardous cluttered space, “ice-breaking” operations to clear the clutter for safe navigation, and positive vessel traffic management to de-conflict operations in the increasingly crowded LEO. Two of the three, the aids-to-navigation function and vessel traffic management could theoretically be undertaken as the space-based technology develops, without resorting to any new international space debris management schemes, because both activities would not interfere with the jurisdictional control of the existing space objects. The third, “ice-breaking” or the active removal of space debris, is likely prohibited by current international law, but may be able to be governed in the near future by a series of bilateral agreements in much the same way the Coast Guard engages with its partners in the Caribbean in the context of its counter-drug mission.

When discussing Coast Guard response missions, it is hard not to bring up the Coast Guard’s bread and butter mission—search and rescue. Space search and rescue is pretty well captured in both the Outer Space Treaty and Astronaut Agreement and it is relatively clear that there is an international obligation for U.S. astronauts to rescue other distressed spacefarers. Yet again though, there is no U.S. authorizing statute that would allow a U.S. government space craft or agency to conduct space-based search and rescue operations. Just as the Coast Guard’s maritime environmental protection statutes and regulations may provide a helpful starting point for planetary protection authorizations and regulation, the Coast Guard’s broad search and rescue authority could also provide a helpful starting point in crafting a space-based version to fill this authorities gap.

But having the right authority to operate is just one piece of the puzzle. In order to truly establish effective space governance, the U.S. government should more fully consider capabilities, capacity, and partnerships for search and rescue, and really, the full spectrum of space activity. The authority to act does not mean a whole lot if there is no capability to execute the action, or the capacity is not sufficient to prove meaningful. Specifically, in the space search and rescue context, this would likely mean some sort of (optimally international) rescue coordination center working with in-space assets that were themselves permanently stationed and in sufficient numbers so that they would be available to render assistance, as needed.

The more actors in space, the greater the number of assets would be required. The farther out these actors operate, the greater the capability for extended or long-distance operations should have to be. As a brief aside, much has been written recently about the fate of the International Space Station. No one, however, has talked about it repurposing it as proto-rescue station, that could serve as a staging and/or resupply area for space rescue assets or perhaps even the aforementioned coordination center. It may have great utility in this regard.

In closing, it’s important to note that a Space Guard should not be confused with a Space Corps or Space Force, currently favored by some members of the House of Representatives and, apparently, President Trump. A Space Guard, like the Coast Guard it should be modeled on, would be a governance agency with defense as one of its many missions and not a single purpose defense agency. A multi-mission space governance agency, with the ability and authority to field lightly armed vessels may provide a helpful counter to what many believe is the inevitability of bad actors such as pirates or terrorists capitalizing on the space domain. Additionally, such an agency operating under the idea that it is at its core, a humanitarian organization focused on rescue and protection of all space actors, may be sufficiently de-escalatory so as to help mitigate against a potential arms race in space—a source of concern dating back to the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik itself, and seemingly resurgent with the increasingly aggressive postures of both Russia and China within the domain.

Many experts apply a maritime analogy when discussing the need for space governance. Thus, it only makes sense to look to the Coast Guard as the United States’ lead maritime governance agency as a model for a unified U.S. space governance agency. Only an agency with the ability to prevent and respond can effectively protect those in space, protect the nation against all threats and hazards delivered from space, and protect space itself.

Michael Sinclair is an active duty Coast Guard officer with 20 years of service. In addition to eight years working as a judge advocate he has served as a patrol boat captain in the Arabian Gulf. He Is finishing a Masters of Law in National Security from Georgetown University and will soon be the Coast Guard’s legislative counsel. The views here are his own and do not reflect those of the Coast Guard or the Department of Homeland Security. For a more in-depth analysis on the prospects of a “Coast Guard” for space, read this draft of his forthcoming academic paper.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.