The US & China: A Colder Peace or Thucydides’ Trap?

Posted on

In late October, Southeast Asian navies held their first-ever joint exercises with their Chinese counterparts. The hope was to ease years of tensions over disputed islands in the South China Sea. Instead, the exercises gave an alarming preview of how Chinese hegemony would work.

During a briefing for officers from the 10-country Association of South East Asian Nations, the chief of China’s Southern Theater Command presented a map including the “nine-dash line” border long used by Beijing to claim dominion over nearly the entire South China Sea — claims the ASEAN members do not recognize. Despite an international tribunal declaring in 2016 that the nine-dash demarcation had “no legal basis” in international law, the Chinese official insisted to his ASEAN counterparts not only that the 9-dash line delineated Chinese sovereignty, but that as head of Southern Theater Command, he was responsible for enforcing those boundaries. According to U.S. officials, the ASEAN naval leaders were outraged — though not surprised — by what seemed like a deliberately insulting provocation by the Chinese.

China has done much more than talk, of course. It has built seven artificial islands on shallow reefs in the South China Sea, all in areas claimed by other countries, and claimed exclusive maritime zones around them in contradiction to international law. As recently as October, a Chinese destroyer nearly collided with the USS Decatur as it was conducting a routine “freedom of navigation” patrol in international waters near the Spratly Islands, prompting Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis to cancel a scheduled trip to China.

Back in 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping tried to calm regional nerves by publicly promising not to “militarize” the man-made islands. Earlier this year, however, U.S. surveillance confirmed the islands now boast military airstrips and facilities and are bristling with anti-ship and surface-to-air (SAM) missiles.

“What my predecessor called a ‘Great Wall of Sand’ three years ago is now a ‘Great Wall of SAMs,’ giving the People’s Republic of China the ability to exert national control over international water and airspace over which $3 trillion in goods travel every year,” said Admiral Philip Davidson. (Davidson, new head of the recently renamed U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, spoke last week via video link to a CSIS conference on China). “The PRC says it’s militarizing these islands in order to defend Chinese ‘sovereignty,’ but in doing so they are violating the sovereignty of every other nation to fly, sail, trade and operate in accordance with international law.”

“The intensifying competition between the United States and China is not just driven by the traditional power politics between an established power and an emerging power, but rather I believe we are facing something much more serious,” Davidson said, in some of the most blunt and pointed rhetoric heard from a four-star theater commander since the Cold War. “I see a fundamental divergence of values that leads to two incomparable visions of the future. I think those two incomparable visions are between China and the rules-based international order.”

“China is looking to change the world order to one in which national power is more important than international law, reflecting a system in which ‘the strong do what they will, and the weak do what they must,’” said Davidson, quoting the ancient historian Thucydides.

What’s needed, many experts argue, is a more muscular U.S. strategy towards China — a strategy informed by the same kind of hard-nosed realism that drove U.S. policy towards the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The United States was able to check Soviet expansionism with a close web of alliances; a combined conventional and nuclear deterrent that matched Soviet capabilities and resisted coercion; and assertive propaganda — what today is called “information operations” — that broadcast the benefits of democracy over tyranny to the oppressed peoples of the eastern bloc. Despite the unavoidable tensions in such a strategy, the United States continued to engage with Moscow on arms control and other areas of possible cooperation., Most crucially, despite proxy wars in Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan, the strategy avoided direct conflict between great powers through four decades of the Cold War.

Chinese aircraft, missile, and radar ranges over the South China Sea. (Graphic by Center for Strategic & International Studies) (Click to expand)

Accommodation Has Failed

Even before the Trump administration initiated a trade war with China involving hundreds of billions of dollars in punitive tariffs, there were signs of a fundamental, strategic divergence that echoes the Cold War. The U.S. had hoped that, by integrating China into a rules-based international order, exposure to Western values and increasing economic prosperity — including a nine-fold increase in GDP since joining the World Trade Organization in 2001 — would moderate the Communist Party’s authoritarian and mercantilist impulses. But a growing number of U.S. national security and foreign affairs experts have concluded that the decades-old strategy of accommodation and engagement with China has simply failed.

Instead, the party has used China’s rapidly accumulating power to crack down on dissent at home, bully its neighbors, and challenge the United States in Asia and worldwide. Engagement with the US has not stopped Beijing from persistently bending the rules of international trade in service to China’s voracious mercantilism, erecting steep tariffs, forcing corporations to surrender intellectual property or compromise their ethics for the privilege of accessing the Chinese market, and outright stealing proprietary technology from U.S. corporations through cyber espionage. Benefiting from other countries’ free markets has not stopped China from launching a 10-year plan to use government subsidies, state-controlled firms, and “military-civil fusion” between the armed forces and private companies to pursue dominance in high-tech sectors from electric cars to artificial intelligence. Entering the global economy has not stopped China from exercising “debt diplomacy” with its “One Belt, One Road” project, loaning hundreds of billions of dollars to often corrupt government officials in underdeveloped nations in order to bind them to Beijing. Exposure to liberal values has not stopped President Xi Jinping from centralizing power, extending his term of office, or — in an alarming echo of the Cultural Revolution — interning a reported one million Muslim Uighurs and other minorities in “re-education camps.”

“What’s happening in west China is a moral atrocity that only adds to Xi Jinping’s abysmal human rights record, even as Beijing is systematically trying to undermine U.S. alliances and expand an illiberal sphere of influence that is already taking root throughout Asia, accelerating a decline of democracy around the world,” said Ely Ratner, a former China expert at the State Department and the National Security Council. “The end result of these trends is a United States that is less secure and less able to exert influence in Asia. So the stakes are extremely high.”

Nor can Chinese pledges of restraint be relied upon. For instance, after promising the Obama administration to cease and desist an extensive hacking campaign to steal technological secrets from U.S. corporations, China has reportedly started up again. On Dec. 1st, Canada arrested the chief financial officer of Chinese tech giant Huawei on charges of subverting international sanctions on trade with Iran: Meng Wanzhou now faces extradition to the United States, where officials believe the company’s telecommunications and networking technology are being used to spy on Americans. On Tuesday, Trump administration officials revealed that they are going to publicly call out China’s aggressive campaign to steal U.S. trade secrets and advanced technologies, pushing back with measures such as having the Justice Department indict hackers working for Chinese intelligence services.

“Contrary to our hopes and expectations China has in the past decade revealed a revisionism and illiberalism that runs directly counter to U.S. interests,” Ratner said at the CSIS conference last week. “On issue after issue our policy of engagement has not only failed to curb this bad behavior, it has actually enabled it.”

The View From Beijing

For their part, Chinese officials openly express their dissatisfaction with the current international order, which they say favors values and interests of the United States and its allies, while overly constraining a newly rising power like China.

Chinese officials and advocates point out that as the lone superpower in a post-Cold War international order, the United States itself has flouted international rules and norms when it suited its interests. The United States and NATO engaged in military operations in Serbia and Libya, for instance, without the backing of the United Nations, where China has a permanent seat on the Security Council and a veto. Likewise, the United States bypassed both the United Nations and NATO in invading Iraq in 2003 with just a “coalition of the willing.”

“China has been a major beneficiary of the current international order, but to call it ‘liberal’ is only partially accurate. We see a liberal, hegemonic order created by the United States and giving you dominant power and the ability to ignore international institutions when they don’t suit your needs, such as when you waged war on Iraq,” said Wu Xinbo, director of the Center for American Studies at China’s Fudan University, said recently at CSIS. “So the international order today is good, but we see too much U.S. dominance and too little respect for the sovereignty of smaller states. So from the Chinese perspective the current international order needs improvement.”

The other side of this Chinese narrative is the strong conviction that after two long and expensive wars and a global financial meltdown with its origins on Wall Street, the United States and the Western democratic model that it represents are in irreversible decline.

The global financial crisis of 2008 was a watershed moment. Fearful that the economic downturn could provoke social unrest, the communist party escaped the worst impact of the meltdown in global markets by engineering a nearly half trillion dollar stimulus package that kept Chinese growth humming. The profound struggles of the United States and Europe, meanwhile, reinforced Chinese convictions that the free market economic model underpinning the international order was deficient and that the West was in rapid decline. The result was a China that in recent years has been even more emboldened and aggressive on the world stage.

“After the 2008 financial crisis China started adopting a much more assertive posture based, as is so often the case throughout history, on a mixture of hubris and fear, ambition and anxiety,” said Princeton scholar Aaron Friedberg, author of A Contest for Supremacy: China, America and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia.

In the short term, Chinese leaders worried about their ability to maintain political control in a major economic downturn. “But after China emerged from the crisis more rapidly than the United States and its allies, the Chinese concluded that the western economic model was flawed in fundamental ways and that America was on the skids,” Friedberg told me. “The Chinese saw an opportunity to take advantage and started talking about their determination to fend off Western liberalization and restore China to its rightful place as the dominant power in Asia. That was always China’s long term strategy, but after 2008 they started dropping the mask.”

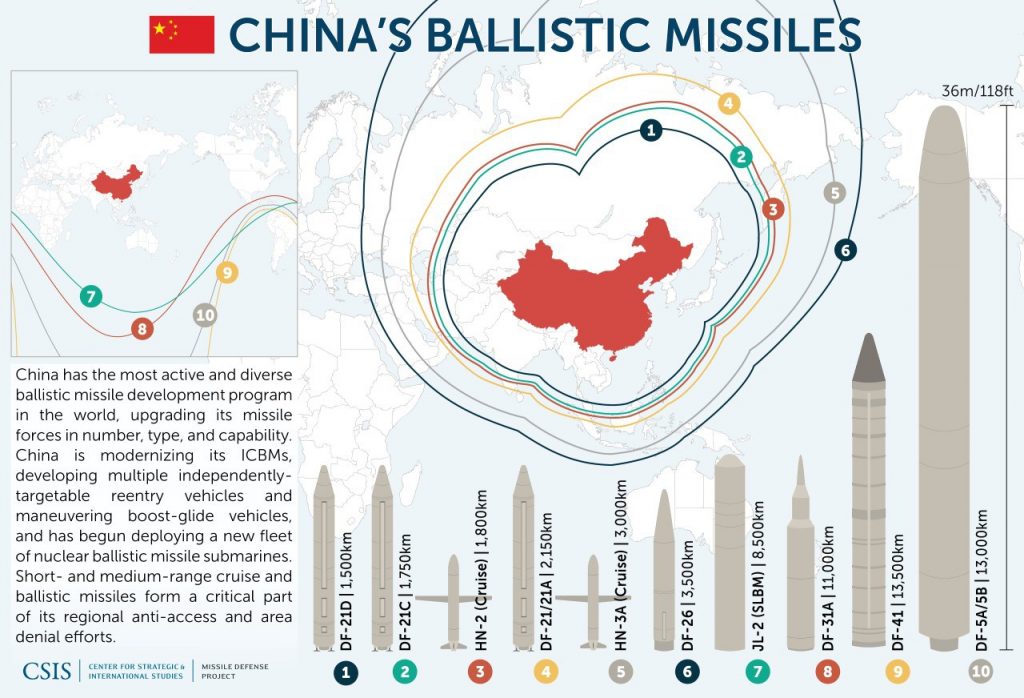

Types and ranges of Chinese ballistic missiles (Graphic by Center for Security & International Studies)

The Lost Decade

With the U.S. military distracted and stretched thin by more than a decade of counterinsurgency operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, China has launched an ambitious military modernization that will be able to challenge the US for dominance in “all domains of conflict – ground, air, sea, space, cyberspace and electromagnetic – throughout the Indo-Pacific” by 2035, according to the think tank RAND. It has built an expanded submarine fleet, a modernized nuclear arsenal, the first Chinese aircraft carrier, a greatly expanded array of advanced anti-ship and anti-aircraft missiles, and a modern command-and-control and surveillance network. Today, China has the world’s largest navy at approximately 350 ships, the largest coast guard, and a “maritime militia” of fishing boats who answer directly to the PLA Navy and routinely harass shipping in sensitive areas in the East and South China Seas. The seven newly militarized manmade islands are also major building blocks in China’s strategy to dominate its near seas, providing permanent forward basing for weapons that can threaten ships and aircraft traffic.

Acting as unsinkable aircraft carriers, “the manmade islands provide a persistent surveillance and weapons platform that could help China establish a regional air defense system, which would be a key element in controlling the South China Sea,” said Bryan Clark, a former special assistant to the Chief of Naval Operations who’s now with the thinktank CSBA. With its large navy and coast guard working in conjunction with a provocative “maritime militia,” he noted, China already has “escalation dominance” — the ability to answer any escalation by other powers with a greater escalation of its own — and thus de facto control of the South China Sea by constantly operating just below a threshold that might provoke a U.S. military response.

“China’s frequent harassment of U.S. Navy ships and the ships of other navies, and its wide array of forces, gives it the tools to climb up or down the escalation ladder as circumstances dictate,” said Clark. The goal is to increase the costs of U.S. operations in the region, he said, in hopes that the U.S. Navy will reduce its activities over time. “The Chinese want to habituate the idea that if you operate in the South China Sea without their approval you are inviting harassment and assuming increasing risk. They want that to be the new normal.”

U.S. military officials recognize China’s military modernization and operations in the South China Sea as pillars in an “anti-access, aerial denial” (A2/AD) strategy designed to impede U.S. operations in the Indo-Pacific, and call into question the U.S. military commitment to regional allies. They claim to have no intention of abandoning “freedom of navigation” operations in international waters despite the persistent threats and harassment.

“We have made clear to our Asian allies our continued support for a rules-based international order that requires the United States to uphold the principle of freedom of navigation by operating wherever international law allows,” General Joseph Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told Breaking Defense in an exclusive interview in Asia last year. “It’s also indisputable that China has militarized those artificial islands after promising not to do so in 2015, which tells me that they are trying to push the U.S. military further out to sea in order to prevent us from having free access to the region to meet our military commitments to allies. That’s a classic A2/AD strategy. If you combine that with China’s pursuit of long-range anti-ship cruise missiles and rocket systems, it’s clear they are attempting to deny the United States the ability to operate freely in the region.”

A Colder Peace or Thucydides’ Trap?

The biggest shift in U.S. strategy towards China came with January’s release of the new National Defense Strategy, which ended the post-9/11 focus on counterterrorism to prioritize countering revisionist great powers like China and Russia. The Trump administration has followed that by initiating a bruising trade war with China by imposing hundreds of billions of dollars in punitive tariffs on Chinese goods, with Beijing retaliating with its own tariffs in a tit-for-tat that is already destabilizing global markets. The administration has also taken steps to restrict Chinese purchases of U.S. tech firms and exports of U.S. technology to China, with indictments and possible arrests in the offing.

Just this November, two congressionally mandated reports highlighted the stakes in what is rapidly becoming a Cold War- style relationship of confrontation, suspicion, and containment. The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission said that “China’s state-led, market-distorting economic model presents a challenge to U.S. economic and national security interests” and its military modernization means “the United States and its allies and partners can no longer assume achieving air superiority in an Indo-Pacific conflict.” Likewise, the National Defense Strategy Commission warned that the U.S. military “might struggle to win, or perhaps [even] lose, a war against China or Russia.”

“These reports independently confirm what The Heritage Foundation had separately concluded – that the U.S. military is far weaker than is commonly appreciated,” wrote Dean Cheng, a senior research fellow at Heritage. “As currently postured, the U.S. military is only marginally able to meet the demands of defending America’s vital national interests.”

Other analysts worry, however, that a U.S. shift to a more Cold War-like posture of pushback and containment of China risks falling into “Thucydides’ Trap.” The reference is to the ancient Greek historian’s recounting how the rise of Athens challenged the established power of Sparta, with an intertwining of “fear, honor, and interest” leading both city-states to mutually destructive war. Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War has been a model for strategists ever since, with Germany’s challenge to Great Britain in two World Wars the most-cited example of his thesis in bloody action.

Graham Allison, in his 2017 book Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap?, calculated that in 12 of the 16 cases throughout history in which a rising power confronted a ruling power, the end result was war. (The great exception is how Britain, the global superpower of the 19th century, overcame tensions with the rapidly rising United States and made the U.S. an ally — but that alliance is based on a unique shared heritage of language, culture, and democratic principles).

“Based on the current trajectory, war between the United States and China in the decades ahead is not just possible, but much more likely than recognized at the moment,” Allison wrote. “Indeed, judging by the historical record war is more likely than not.”

Botching The Strategy

Managing the rise of China without either appeasement or open war will take a strategic sophistication the United States hasn’t exercised since the end of the Cold War. The Pentagon’s sobering National Security Strategy and the Trump administration’s more confrontational stance on trade with China are a start, but they have yet to coalesce into the kind of “whole of government” response needed to successfully manage a dangerous great power competition. President Trump’s own mercantilist instincts, disdain for multilateral institutions and agreements, preference for the company of dictators and transactional approach to allies are also undermining America’s alliances at a time when they need bolstering for the competition to come.

“I’m sympathetic to the general direction the Trump administration is moving vis à vis China, but picking fights with our traditional allies in Europe and Asia over trivial trade issues is shooting ourselves in the foot,” said Princeton’s Friedberg. “Crucial to formulating and implementing a new China strategy will be our ability to articulate the democratic, liberal values that draws us together with our allies and differentiates us from China.”

But will the end of accommodation inevitably lead to a Thuycides-trap conflict? Ratner rejects the idea. “No one is arguing we should cut off diplomacy and dialogue with China, which will be critical in maintaining stability in the coming era of competition, but the National Security Strategy explicitly states that the United States is seeking equilibrium that makes it impossible for any one country to dominate Asia, and that is already happening today,” Ratner said. “Rather, this permissive environment that the United States has allowed to form in the South China Sea is encouraging China to further impose its will in the region, radically increasing the likelihood of conflict down the road when the stakes will be even higher.”

Stapleton Roy, a former U.S. ambassador to China, believes the goal of a revitalized strategy of realistic engagement with China should be an equilibrium that blocks Beijing’s military domination of Asia, curbs China’s worst mercantilist policies, and concedes that outside forces have rarely been able to change the domestic policies of great powers. With the United States still possessing the world’s most powerful military and innovative economy, he said, that should still be well within our reach.

“But don’t underestimate the challenge,” Roy said at CSIS. “China is eager to step into the global leadership role that the United States has largely abandoned, and it’s outspending us in every sphere of power. The harsh reality is the United States poorly used its post-Cold War period of dominance with conflicts in the Middle East and the Great Recession straining our resources and polarizing our politics. Clearly U.S.-China relations should now be at the center of our foreign policy concerns, and handled with great creativity. So far we are not passing that test.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.