The Global Battle Over 5G: Trump And Huawei

Posted on

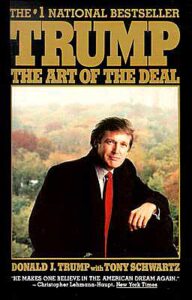

CAPITOL HILL: President Trump may be about to ban Chinese companies from selling high-speed 5G network tech to the US. But the real war against global giant Huawei – and the Chinese spies it serves – is being waged worldwide, two former House intelligence staffers said here today. What’s more, one told me, in order to get wavering governments to pass on Huawei’s lowball prices, the US may have to make concessions on trade and other matters. That, Bryan Smith went on, is the kind of hardball art of the deal that the Trump administration may be ideally suited to make.

“We expect an executive order to come out any minute, actually, ahead of the Mobile World Conference February 25 in Barcelona,” said Andy Keiser, a former senior advisor to the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, who co-wrote a recent National Security Institute study on the threat with his old colleague Smith. “It won’t have a huge impact on our market because they’re such a small player here” – thanks in part to a seven-year crusade in Congress — “but it sends a huge message to the rest of the world that these guys are not to be trusted.”

Sending that message is particularly critical at a time when country after country is deciding what companies get to build new 5G networks. India and Italy remain open to a Huawei bid, at least for now; Britain, Canada, and Germany haven’t decided yet; while France, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand have said no. Britain’s defense minister is said to have expressed “very deep concerns” about any Huawei technology in Britain’s 5G system.

“These are all huge markets,” Keiser said. “All these decisions are happening over the next six to 12 months.”

The problem is that Huawei’s products are just plain cheaper – in part thanks to favorable Chinese government loans and loss-leader tactics. It’s not easy to convince any company or country, especially lower-income ones like India, to give up the clear, immediate benefits of lower cost to protect against shadowy, long-term threats to security.

The problem is that Huawei’s products are just plain cheaper – in part thanks to favorable Chinese government loans and loss-leader tactics. It’s not easy to convince any company or country, especially lower-income ones like India, to give up the clear, immediate benefits of lower cost to protect against shadowy, long-term threats to security.

So, I asked Smith after the briefing, what does the US do? Do we need to subsidize Huawei’s Western competitors somehow? No, he said: We can’t afford to compete head to head on price – but we have plenty of other leverage to use.

“There are a number of things that every country wants from us, so we open up the trade space to incentivize them,” Smith told me. “Maybe it has to do with some policy on, who knows, H-1B visas or some specific trade issue.”

But, given what Smith himself had called President Trump’s “transactional” approach to foreign affairs – some would say confrontational – is this administration the right one to make those deals?

“I think they would open up the window for those kind of discussions,” Smith said. “I think the tactical flexibility they’ve shown in various negotiations will be a tremendous advantage.”

“The Hardest Attacks to Protect Against”

The problem is so fraught that even America’s Five Eye partners – its closet allies who share their most secret intelligence – are split. Australia and New Zealand have already banned Huawei from bidding to build their 5G networks. But Canada and Britain, which already have a lot of Huawei hardware in existing systems, are still struggling with what to do.

Canada’s ongoing review is complicated by fears China will retaliate against a ban, just as its state security agencies seized Canadian citizens on trumped-up charges after Canada arrested Meng Wanzhou, the Hauwei founder’s daughter, CFO, and heir apparent. On the other side of the Atlantic, the UK government requires Huawei to let it test any components the Chinese company is selling in Britain, and British Telecom has promised not to incorporate Huawei technology into the “core” of the future 5G network.

Smith says both these defenses are inadequate. Modern information technology is too complex, and updated too frequently, for lab testing of isolated components today to reveal how they’re actually interact with a full-scale network tomorrow. And one of defining features of the new 5G networks is that they blur the traditional distinction between “core” and “edge,” decentralizing key functions in ways that improve efficiency but undermine traditional security measures based on central control.

The problem with a threat like Huawei is that their hardware and/or software are already in your network, inside your defensive perimeter. Such “supply chain attacks…. are the hardest attacks to protect against,” security expert Jonathan Halstuch told me.

After a career with Defense Department agencies he can’t divulge, Halstuch has co-founded a security company, RackTop, that sells high-end encryption to protect its clients’ data, whether it’s stored in their own facilities or remotely with a cloud provider. But with threats like Huawei, Halstuch told me, the crucial question is, “where are they in the architecture?”

If you can encrypt your data before it hits a compromised component like a network router or a server, he said, you’re probably okay: Yes, the adversary gets a copy of your 1s and 0s, but they’re scrambled, with no way to decipher them. (Unless you were dumb enough to keep your encryption key in the same place as your data, he noted). But if the bad guys actually get their hardware or software on your input device – if they can track which keys your fingers hit, or record the audio of your phone call, and see your raw input before it gets encrypted – well, good luck with that.

That’s why cyber hawks say there’s no safe way for the US and its allies to have Huawei products in their networks. Once the enemy is inside the gates, it’s too easy for them to slip from one part of your network to the others, exploiting the very connectivity that makes networks so useful in the first place.

As former NSC staffer Michael Bahar said during Smith and Keiser’s public briefing at the Capitol Visitors’ Center, “in cyber, any one node is all you need[:] If you can get in anywhere you can get in everywhere.” Modern ships survive collisions, when the Titanic did not, because they’re divided into watertight compartments that can be sealed off completely from one another, Bahar said: We need to start building our networks that way.

As it stands now, however, saying your network is a little bit compromised is a bit like saying someone is a little bit pregnant.

Even the Defense Department, which is forbidden by law from buying Huawei products, is concerned about the larger private-sector networks its data must often traverse.

“You have to ask yourself where are you touching the commercial side … what products like Huawei’s might be in there?” the Pentagon CIO, Dana Deasy, told the Senate Armed Services Committee on Jan. 29. “We have a very good understanding for CONUS [the Continental United States] what that looks like and what those vulnerabilities are. For OCONUS [Outside Continental US], as you can imagine, it’s a lot more complicated, because those networks sit with providers outside of the US.”

Bahar, the ex-NSC staffer, put it more bluntly: “If you’re talking on somebody else’s lines, assume they’re listening,” he said. “Unless …. you control everything from end to end and you encrypt it with your home-grown encryption, you have that to assume somebody else is going to hear.”

Global Stakes

The stakes here are even larger than the Chinese government’s ability to snoop on other countries’ cellphone and internet traffic through bugged Huawei components. Huawei is the Chinese Communist Party’s chosen champion in a campaign to remake global communications by introducing new technologies, negotiating international standards, and capturing a far greater share of profits than mere assembly-line world for Apple. That campaign, in turn, is part of a larger struggle to trying to reshape a Washington-led world order that Beijing sees as deeply tilted against China – for example, by questioning its claims to Tibet, Taiwan, or the South China Sea. One Hong Kong politician even compared the Huawei sanctions to the19th century Opium Wars.

While the Communist Party has leverage over all Chinese companies, which are legally required to cooperate with security services and, often, to have Party members on their boards, its influence is particularly evident with Huawei.

“Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei started his career in the Chinese military, reportedly serving as director of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Information Engineering University, which trains PLA technical specialists in cyber attack and defense,” writes Elsa Kania, a cyber expert at the Center for a New American Security. “Huawei’s former chairwoman, Sun Yafang, once worked for the Ministry of State Security, China’s premier intelligence agency, later leveraging those connections to support the company.”

So what happens to Huawei and other Chinese companies, like ZTE, if the US convinces most major economies not to let them bid to build 5G? “They are likely to continue to survive and grow within China regardless,” said Gregory Allen, also a CNAS senior fellow and author of a recent study on Chinese AI strategy. “The Chinese telecommunications market is large and growing rapidly. Preventing these companies from growing internationally would not threaten their solvency in the same way that US semiconductor export bans threatened ZTE.”

(The Trump administration lifted a ban on US manufacturers selling ZTE essential components and has reportedly tabled any proposal to enact a similar ban on Huawei, which would be far more damaging than the Executive Order now in the works).

“However, restricting or even just delaying growth has major implications for the stock value of these companies, [which are] based on the assumption of major international growth,” Allen said.

Of course, the goal isn’t to hurt Huawei for the sake of hurting it: It’s to protect Western security and economies. “What does winning look like? Winning is having a Western-valued company that actually makes this stuff,” Keiser said. “Huawei was on a trajectory to put everyone out of business” – which would have left even the US with no alternative for 5G.

“In many ways,” said Bahar, “data is the new gold bullion or the new oil that countries around the world are basically competing for.” Just as the UK and then the US kept the sea lanes open for commerce for over 200 years, he said, we now need to “keep the global sea lanes of data open.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.