Taiwan, Trump, & The Pacific Defense Grid: Towards Deterrence In Depth

Posted on

Taiwan lies deep inside the kill zone of Chinese land-based missiles, let alone air and naval forces, as shown in this CSBA graphic.

The phone call between President-elect Trump and the President of Taiwan sent shock waves through the diplomatic community. But it is time to turn the page and include Taiwan in shaping a 21st century deterrence strategy for Pacific defense.

The People’s Republic of China has made it clear that the regime is moving out into the Pacific, asserting its power and influence, and directly threatening U.S. interests and U.S. allies. It is reaching beyond Taiwan in its military and diplomatic strategy, using its expanded capabilities for power projection into the Pacific to reach out to the Japanese island chains as well as the key maritime access points to Australia.

It is clear how important control of Taiwan would be it shaping a pincer strategy against Japan, Australia, and American military installations in the Pacific. Why would the United States then simply stand by and ignore the defense of Taiwan and its key place in a strategic reshaping of Pacific strategy? That would be turning the Pacific Pivot into the Pacific Divot.

Richard Nixon

There is little reason to be frozen in time with Kissinger and Nixon who sought to counterbalance the Soviet Union by embracing Communist China. Last time we looked, the Soviet Union had collapsed. Russia is not the Soviet Union: Today’s Kremlin sees no commonality of relationships with China, except and only with regard to realpolitik. As such, there is little to be gained by appeasing the PRC in hopes of containing Russia. Deterring Russia is a task all unto itself, as it forges a 21st century approach to power, using its military capabilities to shape outcomes seen as essential to Russian national interest by Putin. And today China is a power unto it itself, one that has departed dramatically from its place in the global system when Nixon and Kissinger negotiated the Shanghai Communiqué.

As Danny Lam, a Canadian analyst, has underscored: “Normalization of relations with the PRC was accomplished through the issuance of three communiqués in 1972, 1979, and 1982 that defined the relationship. In those documents, the PRC and US explicitly acknowledged their differences….and made clear that the differences are only papered over temporarily for the sake of peace. Temporarily is the operative word.”

This was converted to the “one China policy” at the end of the Carter Administration, where Carter severed diplomatic relations with Taiwan and recognized the PRC as the sole legitimate government of China.. But Carter’s policy was also forged during the Cold War with what is now the non-existent Soviet Union and before China turned into a military power seeking to assert that power deep into the region. It is time to exit the Madame Tussaud museum of policy initiatives and shape a Taiwan policy for the 21st century, which is part of a broader deterrent strategy.

The Nimitz-class aircraft carriers STENNIS (foreground) and REAGAN (background) operate together in the Pacific.

Deterrence In Depth

Both the technology available to the United States and the policy shifts of core allies in the Pacific enable a new strategy of deterrence in depth. Japan has focused on its extended defense; Australia upon the integration of its forces with a capability for the extended defense of Australia; U.S. forces on shaping a force to operate over the extended ranges of the Pacific. Now is the time for a serious rebooting of the role of Taiwan in extended Pacific defense and security.

Lt. Gen. Terry Robling (left) samples purified water in a disaster relief exercise in Brunei.

As then-commander of Marine Corps Forces Pacific (MARFORPAC), Lt. Gen. Terry Robling, put it: “I like the term deterrence in depth because that’s exactly what it is. It’s not always about defense in depth. It’s about deterring and influencing others’ behavior, so they can contribute to the region’s stability, both economically and militarily, in an environment where everyone conforms to the rule of law and international norms.”

How to implement this approach militarily? U.S. Navy leadership has pioneered the concept of building integrated kill webs, which network together widely dispersed assets — ships, planes, submarines — across the extended battlespace, allowing new combinations of sensors and shooters in which “no platform fights alone.” Taiwan can be seamlessly integrated into such a deterrence strategy with the political will expressed by President-Elect Donald Trump.

In our discussions with the new Deputy Chief of Naval Operations, Rear Admiral Mike Manazir, he highlighted the key role of integrated forces across a distributed operational area. It is clear that both the Air Force, the Navy and Marine Corps team are focused on shaping the force for the high-end fight against peer competitors.

The Army’s main contribution in such considerations is the expanding and evolving role of Army air and missile defense systems. But in so doing, the focus is upon building a modular, agile force, which can operate across the spectrum of military operations, not only in the high-end fight. It is about shaping platforms into an integrated force, which can deliver lethal and non-lethal effects throughout the battlespace.

Taiwan can enter easily into a system of distributed defense and deterrence in depth. One can start by involving them in various security efforts associated with allied coast guard forces in the region. The Taiwanese can become a regular participant as a presence force associated with allied and U.S. security operations.

Taiwan’s Air Force and Navy can engage in partnership in the evolving distributed approach to an integrated Pacific defense strategy. Against a PRC pushing out its military capability into the Pacific, if Taiwan is isolated unto itself and not part of a US-Japanese-Australian deterrence in depth force, the lonely island will become an apple for Beijing to pluck from the tree. President Elect Donald Trump’s phone call put a very powerful marker down for a new chapter in deterring the PRC.

As we wrote in our book on Pacific strategy published three years ago, Beijing sees Taiwan from the perspective of holding their control over the centrifugal forces in their empire:

The conflict with Taiwan is subsumed in Chinese thinking as part of the core territorial-integrity challenges.

The Island of Formosa was part of China since its conquest in the Qing Dynasty in the 17th century. It was ceded to Japan in 1895 and returned to China after the war.

In the ensuing Chinese civil war, the forces of Chiang Kai-shek were pushed off the Chinese mainland and relocated to Formosa. Here the Republic of China was established.

Over time, the Republic of China has evolved into a vibrant democracy, and it is the quality of Taiwan as a modern democracy that is a major challenge to the authoritarian Chinese leadership on the mainland.[1]

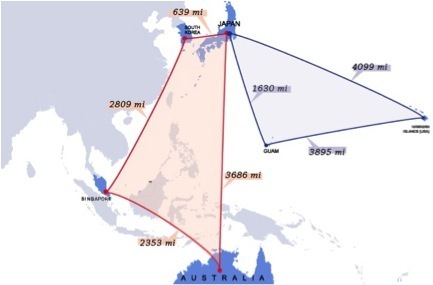

US military bases on Guam are literally the center of the new Pacific strategy. (Map courtesy Robbin Laird).

Taiwan As Cornerstone

A new Taiwan policy and indeed a new approach to Pacific islands is a key part of any new “constrainment strategy” towards China. Taiwan lies at the juncture of any effective Pacific military strategy against the PRC coming out deeper into the Pacific. The PRC has changed the nature of the game. Neither Taiwan, the United States, Japan, nor Australia should accept Chinese encroachment on freedom of the sea in the Western Pacific and South China Sea.

A PRC-dominated Taiwan would be militarily poised to disrupt US and allied operations and significantly disrupt the ability to operate in a “strategic quadrangle.” If the PLA (generic for all PRC military forces) is given time to dig in and build a robust redundant intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) network from survivable, hardened ground facilities with dug-in and hardened missile batteries, it would be a significant new combat challenge. The combination of survivable ISR 100-plus miles off the Chinese coast, linked with sea-based platforms, PLAAF attack planes, and their satellites (if they are allowed to survive) could be very deadly at sea for the US Navy and allied forces.

Enhancing the defense of Taiwan is a legitimate right of Taiwan and is permitted by the Taiwan Relations Act: “In furtherance of the policy set forth in section 3301 of this title, the United States will make available to Taiwan such defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability.”

But self-defense of Taiwan against a PRC reaching deep into the Pacific cannot be done without collaboration with the US, Japan and Australia in a broader strategic effort. We can look for ways to both enhance Taiwan’s ability to defend itself and contribute to Pacific defense. One key way would for Taiwan to extend the reach of their Intelligence, Surveillance, & Reconnaissance (ISR) into the area and enhanced their Command & Control (C2).

THAAD missile launch.

These capabilities could evolve further as the US Army builds out its Air Defense Artillery (ADA) capability in the region. A new way to think about the ADA approach is to build the support facilities throughout the Pacific whereby THAAD missile defense systems and other air defense can be supported.

How can we deploy THAAD batteries to remote islands, as part of a flexible network of defensive systems? The Gross Vehicle Weight Rating (GVWR) of a truck-mounted THAAD missile launcher alone is 66,000 lbs, while the heavy lift CH-53 helicopter can take only 30,000 lbs internally or sling-load 36,000 externally (range unrefueled is 621 nautical miles). However, the actual missile battery — separated from the vehicle carrying it — is 26,000 lbs and well inside the lift capacity of a CH-53.

The problem is the mechanisms to raise and lower the launcher and rearm. A launcher (sans truck) might be lowered from the air onto reinforced concrete pads with calibrated launch points. Or, a separate modular lift device could be put in place to load and reload. Consequently, taking apart modules doesn’t appear to be a showstopper. As for deploying the crews, Marine MV-22 Opsreys flying in Army ADA troops into any reasonable terrain is absolutely no problem. (The weight of the THAAD command post and radar may be of concern, however).

CH-53K

To date, the Big Army has not spent much time thinking about using MV-22s and CH-53Ks, which are exclusively Marine Corps systems. But there is precedent for such operations:In the Vietnam War, the Army did it brilliantly by setting up firebases in remote areas with helo lift of very heavy guns. A THAAD island deployment concept is the same in principle but with different technology.

Now combine these deployable ADA batteries with the ability to move a floating airfield as needed, the aircraft carrier carefully staying within 200-plus kilometers of the dispersed island bases so the land-based batteries can help protect it. As the US shapes such a defensive belt, Taiwan could be plugged. At some point in the future, as the island nation develops its own Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, & Reconnaissance (C4ISR) capabilities, Taiwan could operate its own air defense artillery and contribute to the firepower of the defensive grid.

The Taiwan Relations Act clearly permits such actions: “To maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.”

President Trump has started the process of setting in motion a new policy. History may remember when Donald Trump took a phone call from President of Taiwan as a symbolic moment embodying the same moral imperative as Ronald Reagan’s demand in Berlin to “tear down this wall.”

[1] Laird, Robbin; Timperlake, Edward; Weitz, Richard (2013-10-28). Rebuilding American Military Power in the Pacific: A 21st-Century Strategy: A 21st-Century Strategy (Praeger Security International) (pp. 25-26). ABC-CLIO. Kindle Edition.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.