Star Wars At Sea: Navy’s Laser Gets Real

Posted on

PENTAGON: The age of laser weapons has officially begun. Since September, the Navy has had a $40 million, 30-kilowatt Laser Weapons System (LaWS) aboard the USS Ponce in the Persian Gulf. “They’re using it every single day,” said the Chief of Naval Research, Rear Adm. Matthew Klunder. Sailors — not contractors or engineers — perform basic maintenance, train on the Xbox-style controls, destroy practice targets such as drones, and spy on suspicious ships and aircraft, using the laser’s sophisticated optics as a sort of super-telescope.

While the US hasn’t fired a laser in anger, yet, the Pentagon has worked out rules of engagement and given the commander of the Ponce full authority to unleash the laser if he deems it necessary to the ship’s defense. “Please make no mistake, if we have to defend that ship today, we will destroy a threat if it comes in,” Klunder told reporters today at the Pentagon.

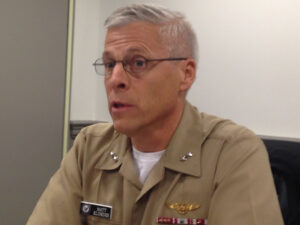

Rear Adm. Matthew Klunder, Chief of Naval Research

“The captain of the ship has all the authorities necessary.”

One advantage lasers have over bullets, missiles, and other physical weapons is “scalability,” added the Navy’s chief engineer, Rear Adm. Bryant Fuller of Naval Sea Systems Command. (In the Navy’s puzzling rank structure, Fuller is a one-star “RDML,” Klunder a two-star “RADM”). If a suspicious vessel or aircraft approaches the Ponce too closely, the laser operator can start out in a low-power “dazzling mode,” enough to catch the target’s eye but not enough to do any damage. If the potential threat keeps coming, though, the laser can dial up to higher power levels: frying sensors, burning out motors, and ultimately detonating anything explosive that the target might be carrying. By focusing on vital points, Ponce sailors have reduced the time to shoot down a drone to “less than two seconds,” Klunder said.

For manned targets, however, the complication is the Geneva Convention’s prohibition on weapons that blind — which lasers do at certain power levels. That’s part of the reason it took “about a year” for Pentagon policy officials to thrash out rules of engagement, Klunder said. International law and US policy boil down to “you will not point lasers at people,” Klunder explained. “We certainly honor that.”

“If there are people on a vessel…trying to kill you….well, we’re not going to aim it at the people, but we’re going to aim it at the ship,” Klunder said. “If we have to blow up the ship, well, you were on the ship.”

The Navy’s Laser Weapons System (LaWS) aboard the USS Ponce in the Persian Gulf

“It’s more effective if we take out the platform,” Fuller said: Destroying sensors, weapons, or engines is a more effective way to neutralize a threat than zapping individual crew. (The two admirals didn’t specify what happens if the full-power beam does hit a human, but presumably it’s messy). As the Navy video at the top of this article shows, the laser can focus precisely enough to destroy a single rocket-propelled grenade mounted on an (unmanned) small boat — a proxy for the kind of improvised fast attack craft used by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps. But the video also shows the RPG detonating in a cloud of shrapnel that would probably kill the Iranians anyway, even if the laser technically never fired at them.

The Navy has tested using the laser against an incoming swarm of Iranian-style attack boats, Klunder said. They didn’t actually blow up the boats — that gets expensive, he said — but they practiced training the laser on one boat, holding the beam on target for the “one or two seconds” required to burn out some vital component, then moving on the next boat, and the next, and the next, in rapid succession.

How big a target can this laser kill? “We can disable [a] rather large craft or helicopter,” Klunder said. An aircraft, of course, would then crash; a boat would be “dead in the water.”

Faster-moving targets, however, will have to wait for future, higher-powered lasers. By 2016 or 2017, the Navy expects to install a 100 to 150-kilowatt laser aboard a ship, Klunder said. “That will expand the [target set] beyond UAVs and fast-attack craft,” he said. So while “a lot” of current ships could accommodate the current 30-kw LaWS, he said, “the 100-150 [kw] one, that’s the one we’re really targeting for potential more extensive use.”

Rear Admirals Klunder (left) and Bryant Fuller (right).

At that higher power level, it may be possible to achieve what’s been a holy grail for lasers since Ronald Reagan: shooting down incoming missiles. Klunder and Fuller said the Navy was looking at that mission for the 100-150 kw laser, though they didn’t promise they could do it. They did compare the current laser’s cost per shot – $0.59 worth of electricity — to the hundreds of thousands of dollars or even millions for current anti-missile interceptors like the Navy Standard Missile: A missile defense laser would be much cheaper and have infinitely more shots than a battery of interceptors.

A lower-powered laser like the one on Ponce is a much more limited and specialized tool. Perhaps the most surprising side benefit, however, is that the same high-quality optics, stabilization, and targeting algorithms required to aim the laser can also serve as a super telescope. So in addition to its primary defensive purpose, said Klunder, “we also now use this on an everyday basis on targeting and identification of potential threats.”

“[If] you see an air contact that’s out on the horizon, your naked eye can see it’s a little dot,” added Fuller. “With binoculars, you can make it out as an airplane; with this….”

“….we can precisely tell what’s its carrying, who it is, what it’s doing,” Klunder broke in.

We can “read the tail number,” Fuller said.

What’s more, this refined instrument manages to hold up under the real-world conditions of the Persian Gulf. “We wanted the harshest environment you could get so we could run it through its paces,” said Klunder, noting the Gulf’s combination of extreme heat, humidity, and dust.

“This system [LaWS] withstood a 30-knot dust storm,” Klunder said. “The very next day we went and checked it, it was spot-on alignment. We didn’t have to do any kind of readjustments.”

Navy personnel operate the LaWS laser system aboard the USS Ponce

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.