Six Retired Generals Make The Case For LRSB

Posted on

Boeing B-29 bombers raid Burma in World War II

Northrop Grumman Long Range Strike Bomber

By Gen. Larry Spencer, Lt. Gen. David Deptula, Lt. Gen. Richard Newton, Lt. Gen. Chris Miller, Maj. Gen. Curt Bedke, and Maj. Gen. Mark Barrett, all US Air Force (retired)

Tuesday’s bomber award announcement by the US Air Force marks a critical achievement for US national security. Global Vigilance, Global Reach, and Global Power—the ability to find and strike targets anywhere in the world at any time—is a core capability for our nation. When North Korean provocations occurred in 2013, an Air Force B-2 flew over the Korean peninsula to deter hostile action. When Russia recently invaded Ukraine, B-2s and B-52s deployed to England to reassure NATO allies.

During the initial phases of every major application of US power over the past 40 years, bombers have led the first strikes because of their range, speed, and payload. Operating from assured bases, long-range strike aircraft allow the US to create desired effects unachievable by any other means.

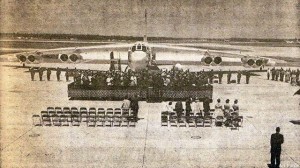

10 percent of the nation’s B-2 bomber fleet — totaling just 20 aircraft — is in this photo.

However, the bomber fleet averages over forty years in age. While some of our bombers are still capable in permissive threat environments, the proliferation of advanced air defenses is shrinking where and when our old bombers can successfully operate. To put it bluntly: a B-52 or B-1 is at high risk of getting shot down in an advanced air defense environment. Today, 87 percent of the bomber force predates modern stealth technology. Twenty B-2s are the only long-range aircraft that can access a high-threat environment and survive—and only about half that number at any one time.

Our last B-2 rolled off the assembly line in 1997, leaving no viable replacements to backfill losses. We simply built too few. When a B-2 crashed in Guam in 2007, the US lost 5 percent of its stealthy long range strike fleet. The B-52 and B-1 have been upgraded to take advantage of new technology, but stealth can never be backfitted into these aircraft. They are increasingly vulnerable to attacks by modern surface-to-air missiles and fighters. In the final days of the Vietnam war, the Air Force lost 15 B-52s in 12 days during Operation Linebacker II; today, 47 percent of our long range strike force is comprised of these same B-52s, and air defenses have evolved a great deal since Vietnam.

The Air Force’s B-52 bombers entered service in 1961.

The ability to strike targets through the air at great distances has served the United States well for three-quarters of a century. Since the opening days of World War I, Airmen looking down at the carnage of ground warfare saw a better way. Instead of engaging in grinding ground operations, early flyers realized that the air allowed them past fixed battle lines and target enemy centers of gravity. Striking the right targets could gravely weaken an enemy force. The vision was prescient, but it took nearly 80 years for technology to mature to a point where aerospace systems could align range, payload capacity, survivability, and precision weaponry to consistently transform vision into reality.

While some rudimentary long-range strikes did take place in WWI, aircraft of this period were too primitive to have a meaningful impact. By World War II, bombing hastened the end of the war by destroying key targets. However, technology of the era lacked precision and the bombers were far from invulnerable: over 6,000 B-17s and B-24s were lost in the European theater alone, and tens of thousands of Airmen were killed—more than all the Marines lost in WWII.

During the Cold War, the payload capacity of bombers increased markedly, and aerial refueling extended their range, transforming them into a truly global force. They played a critical role in deterring the Soviet Union. By the end of the Cold War, developments in precision-guided munitions and stealth technology finally transformed the long-range strike force into that envisioned by airpower theorists, and needed by national leadership. The B-2 emerged as the first system truly capable of mounting a precise and effective bombing campaign anywhere in the world, at any time, against any threat—but we built too few of them and they are aging.

A B-1 bomber test-fires a LRASM anti-ship missile

Tuesday’s contract award marks the next step in advancing our nation’s defense with the new bomber moving from the drawing board to the production line. This capacity will stabilize key regions in times of peace; deter aggressors; reassure allies; and yield war-winning effects during time of war. Having long-range, high payload, and low observability in an aircraft that can conduct multiple missions spanning the spectrum of operations is an asymmetric advantage of the US. Given the imperative of these capabilities to keep our advantage as the world’s sole superpower, the geriatric age of most of the force, and its dwindling effectiveness, one thing is clear: the United States needs this new bomber.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.