SASC NDAA: McCain Kills Kendall’s Job, F-35 JPO, 25% Of Generals

Posted on

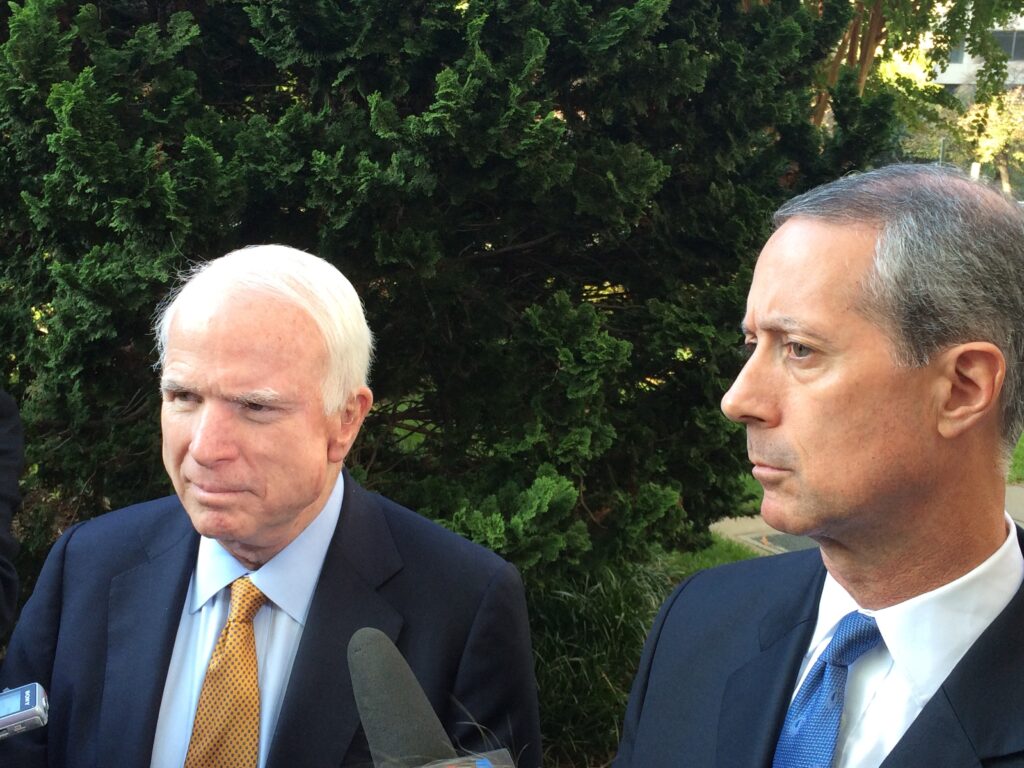

Sen. John McCain and Rep Mac Thornberry, chairmen of the Senate and House Armed Services Committees

UPDATED from SASC briefing WASHINGTON: In their dueling drafts of the annual defense bill, Senate Armed Services Committee chairman John McCain has staked out bold positions where the House’s Mac Thornberry is cautious — and McCain is cautious where Thornberry is bold.

Specifically, according to a summary his staff released last night, McCain’s bill is bold on organizational reforms, notably slashing 25 percent of the general officer corps and splitting the Pentagon’s Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics undersecretariat in two. But McCain is cautious on fiscal matters, sticking to last year’s budget deal, whereas Thornberry uses fiscal sleight of hand to effectively move $18 billion from war funds (Overseas Contingency Operations) into the base budget. Those differences set the two pro-defense Republicans up for either a hard-won compromise or the first failure to pass the annual National Defense Authorization Act in 55 years.

Frank Kendall

Blowing Up Acquisition In Order To Save It

Both Rep. Thornberry and Sen. McCain are defense reformers. But Thornberry is a naturally cautious lawyer who works closely with the Pentagon, earning public praise from the Pentagon’s top procurement officer, Frank Kendall. McCain, at heart, is still a hot-shot fighter pilot — and he wants to abolish Kendall’s job. That’s just one of the big changes the SASC chairman wants to make to the Defense Department.

The draft SASC bill splits Kendall’s powerful position, the Under Secretary for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, into two. [UPDATE: “This is not about Frank Kendall,” a SASC aide told reporters. “This is about the job he’s got, which is too big” for any one person]. An Under Secretary for Management and Support would handle, in essence, all the boring stuff, what the summary calls “running defense agencies” — such as the Defense Logistics Agency — “that perform critical business operations of the Department of Defense.” An Under Secretary for Research and Engineering would do the fun stuff, spearheading high-tech innovation.

Further, “to enable the USD(R&E) to focus on the innovation mission,” the summary says, the SASC NDAA would give him or her an Assistant Secretary to handle the nitty-gritty of “setting defense-wide acquisition and industrial base policy and overseeing the development of weapons.” Meanwhile the seven assistant secretaries and deputy assistant secretaries serving the current ATL bureaucracy would be abolished. So, for that matter, would be the Joint Program Office running the F-35 program, whose variants would be managed separately by the services, with a separate program for upgrades (the House rejected a similar split).

F-35B

Creating an undersecretary of research & engineering is a “back to the future” solution: There used to be such a position in the Pentagon. What’s more, the summary argues, the old USD(R&E) played a leading role in the high-tech revolution of the times, the 1970s and ’80s advances in stealth, smart weapons, and computer networks that won the First Gulf War, collectively called “The Second Offset Strategy.” (The First Offset Strategy is a name retroactively applied to the introduction of tactical nuclear weapons to offset Soviet numerical superiority). Now the Pentagon is attempting a Third Offset Strategy — centered on artificial intelligence — and, SASC argues, it needs an undersecretary devoted to research & engineering to make it happen.

Needless to say, Frank Kendall will not consider this a good idea. The obvious criticisms are that it creates two bureaucratic fiefdoms in the place of one and slights the hard work of management in favor of more exciting “innovation,” the Pentagon buzzword du jour. Even setting aside the merits of the proposal — and it deserves debate — there will be tremendous resistance due to institutional inertia alone. If it’s enacted, for good or ill, there will be tremendous disruption before the new system starts working smoothly.

[UPDATE] SASC aides argued the reorganization would streamline bureaucracy, not increase it. First, it builds on last year’s legislation devolving many acquisition responsibilities from the the centralized Acquisition, Technology, & Logistics undersecretariat to the individual services. Second, to retain strong central oversight of what the services get up to, the bill strengthens the famously hard-nosed Director of Operational Test & Evaluation (DOT&E). Third, again building on earlier legislation, it turns the Pentagon’s Chief Management Officer (CMO) from an afterthought — it’s currently an additional responsibility of the Deputy Secretary of Defense, largely delegated to the deputy’s deputy — into a full-fledged undersecretary position that can take over many mundane managerial duties that once bogged down AT&L.

You want the reinvented AT&L — the new undersecretary for research and engineering — to be “the chief technology officer instead of the chief compliance officer,” said one staffer, focused on the future instead of drowning in administrivia.

But isn’t this great devolution of responsibilities undoing the landmark 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act reforms, which established the current centralized oversight? No, one aide told reporters. “It’s not like the last 30 years never happened,” one said. Crucial oversight organizations — the Director of Operational Test & Evaluation and the office of Cost Assessment & Program Evaluation — have been created since ’86, back when the services were running around unsupervised and over budget. The existence of DOT&E and CAPE makes it safe to dismantle some of the ATL oversight bureaucracy that’s built up over the years (though good luck convincing Kendall of that).[UPDATE ENDS]

But that’s hardly the only disruption McCain intends to create in the Pentagon.

Gen. Joseph Dunford, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Changing The Chain of Command

While both Rep. Thornberry and Sen. McCain are passionate advocates of acquisition reform, albeit with different approaches, McCain has a more idiosyncratic passion for reforming the chain of command. Both men have proposed capping the size of the (arguably dysfunctional) National Security Council staff, but McCain’s bill would also cut the general officer corps, give new powers to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and experiment with new organizations for the Combatant Commands.

All these reforms reflect the retired Navy captain’s desire to build on the work of his Arizona Republican predecessor, Sen. Barry Goldwater. The 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act radically improved the ability of the four armed services to work together (“jointness“), but arguably at the price of more bureaucracy. McCain seeks to cut that bureaucracy back in often-controversial ways, like last year’s successful push to give the four service chiefs more acquisition authority at the expense of the undersecretary for acquisition (the same position he’s seeking to disestablish this year).

The most obvious shock to the system in this year’s bill is a 25 percent cut to the ranks of generals, admirals, and their civilian equivalents, the Senior Executive Service. The cut is even steeper at the highest ranks, with the number of four-star officers dropping by a third, from 41 to 27. The bill also cuts spending on civilian contractors by 25 percent. (There’s no good count of the total number of contractors, just of the total spending on them).

Sen. Barry Goldwater

There are subtler changes as well. American political culture has always been hostile to the idea of a Prussian-style General Staff. As a result, the US equivalent, the Joint Staff and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, began as painfully weak institutions that strengthened slowly over time. (Amy Zegart’s Flawed By Design is my favorite treatise on the topic). “At present,” says the summary, “the Chairman {of the Joint Chiefs) is not in the chain of command, which was one way that the Goldwater-Nichols Act sought to guard against an over-centralization of military power in the Chairman’s hands and protect civilian control of the military.”

As a practical consequence, the military cannot even do such things as move forces from one theater Combatant Command to another without the Defense Secretary’s permission. In an era of increasingly transnational and swift-moving threats that do not respect our geographic jurisdictions, SASC argues, this is too inflexible. So the bill “would allow the Secretary to delegate some authority to the Chairman for the worldwide reallocation of limited military assets on a short-term basis.” It’s a very limited step towards putting the chairman in the chain of command, but it’s still a step.

[UPDATE]: Assisting the chairman will be a “Combatant Commanders Council, consisting of all the COCOMs, the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Secretary of Defense.” This body builds on existing practices that aren’t institutionalized, such as the Senior Leadership Council, and enshrine them in law. In essence, the COCOMs council would do for global coordination of operations what the Joint Chiefs of Staff do for inter-service coordination of training, organization, and equipping.

The current Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Joe Dunford, has suggested creating a new staff to handle such cross-COCOM coordination, but a SASC aide said the envision the council simply as a forum for the COCOMs that won’t need its own dedicated staff, a SASC aide said. After all, he argued, its head is the Secretary of Defense, who has hordes of staff, and its No. 2 is the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who owns the Joint Staff. That said, the SASC staffer acknowledged, this is just one step in a years-long process of reform that could one day change the Pentagon much more radically. [UPDATE ENDS]

The bill also takes measured but serious steps towards reorganizing the nine combatant commands (COCOMs) which control almost all operational forces. Currently, each COCOM has four “service components,” one each from the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps, but for actual operations the services must blend their forces into Joint Task Forces (JTFs). The SASC bill would replace all the service component commands with JTFs — albeit only in one COCOM of the Defense Secretary’s choosing, as a pilot project.

McCain would also create a new cyber chief. This Assistant Secretary of Defense for Information would both act as the department’s Chief Information Officer (CIO) and oversee cyberwar, the Defense Department network, and space (on which long-range network communications depend). These closely related responsibilities are currently divided across the department.

But the bill also recognizes that you can’t simply create a new czar for every problem that doesn’t fit the traditional bureaucracy: Ultimately, you need a way to work across bureaucratic seams. To do this, McCain would authorize the Defense Secretary to create “mission teams” of officials from different parts of the Pentagon to collaborate on cross-cutting problems. “Each mission team would focus on a discrete mission (deterring Russia, for example, or cybersecurity) that the Secretary could determine,” the report says, although what actual authority they would have is unclear.

President Obama meets with his National Security Council.

The bill also tears up some traditional reports: Like the House bill, it would end the bland and bureaucratic Quadrennial Defense Review. SASC would replace it with a classified National Defense Strategy, while HASC would replace it would a one-time commission of experts, but these are hardly irreconcilable differences.

There’s also common ground at the highest level, looking above the Pentagon to the White House, McCain would cut the National Security Council staff from the current 400 or so down to 150. While there’s no comparable provision in the HASC defense bill, Rep. Thornberry has introduced an amendment that would cut the NSC staff to 100. It’s one of the rare areas where Thornberry’s a bit bolder than McCain — but not by much.

That means there’s at least one institutional reform on which the two men can come to a quick compromise. The rest of the bill won’t be so easy.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.