Russia’s Real Target Is US Alliances & Ukraine, Not Elections: CIA Veterans

Posted on

CENTER FOR THE NATIONAL INTEREST: Vladimir Putin’s Russia is not targeting America’s elections but its alliances, three ex-CIA experts said here, and Russia’s chances of doing so look better than ever. Interference in US elections is probably retaliation for American support of pro-democracy movements in places the Kremlin really cares about, especially Ukraine, which they are desperate to keep out of NATO.

Russia was not seriously trying to get Trump elected in 2016, agreed George Beebe, former head of Russia analysis at the CIA, and fellow CIA veteran Peter Clement, former director of the Office of Russian and Eurasian Analysis. If the Russians had really wanted to create an electoral crisis, they could have done far worse than troll farms and fake news. What if, instead just probing electoral systems, they had actually hacked the vote count in key states, or even just leaked information claiming they did?

Instead of trying to get Trump elected, Clement said, the Kremlin was taking revenge on Hilary Clinton, hoping to undermine her probable presidency. Why? Because, as Obama’s Secretary of State, she had supported democracy movements and “color revolutions” against pro-Putin autocrats in Ukraine and other places. It’s the spread of democracy in Russia’s “near abroad,” not democracy 4,000 miles away in the US, that Putin sees as an existential threat.

The three retired spooks made their observations before the contentious G-7 summit, but events at the G-7 only support their point about the vulnerability of US alliances. President Trump entered the meeting threatening trade war with America’s closest allies and urging the group to readmit Russia. He departed a day early — skipping sessions on the environment — while denouncing the joint communiqué the US had already signed.

The three retired spooks made their observations before the contentious G-7 summit, but events at the G-7 only support their point about the vulnerability of US alliances. President Trump entered the meeting threatening trade war with America’s closest allies and urging the group to readmit Russia. He departed a day early — skipping sessions on the environment — while denouncing the joint communiqué the US had already signed.

“We were far less vulnerable across the board during my time,” lamented Milton Bearden, who headed the CIA stations in both Moscow and Islamabad and ran the covert support to the Afghan insurgency against the Soviets. The Cold War alliance had its strains, but US commitment took the tangible form of over 300,000 young men on European soil. For their part, the Soviets reminded everyone of the threat with periodic barbarities such as Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, or Afghanistan in 1979. “Today it’s different,” Bearden said. “I think that the Europeans, at this point, could manage to believe almost anything about the United States.”

That’s not to say Trump is doing what Russia wants. To the contrary, “there’s got to be some disappointment there (in the Kremlin),” Beebe said. Trump made campaign promises to pull out of regional conflicts, for instance, but then reinforced the US presence in Afghanistan and bombed the Assad regime in Syria, both countries Russia sees as its sphere of influence.

The Best Defense, Moscow-Style

From a Russian point of view, meddling in US elections is something “you can to some degree construe as defensive,” Beebe said. “They want us to knock off the democracy crusade. Democracy by itself doesn’t threaten them, but threatening to spread democracy abroad — and in Russia itself — (that) they find threatening.”

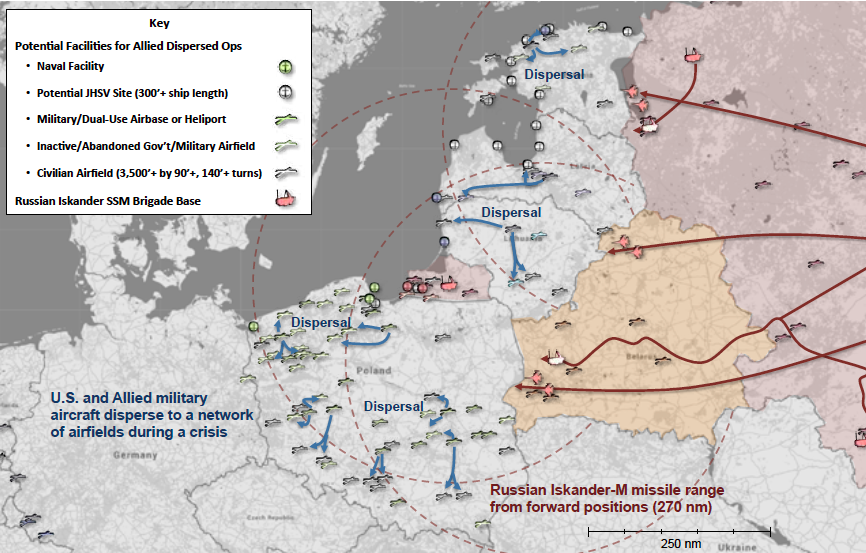

It’s hard for Americans to appreciate the deep sense of vulnerability caused by Russia’s history of successive invasions by Mongols, Poles, Swedes, French, and Germans. With few natural defensive barriers to the east or west, Russian elites have generally sought security in accumulating military power and territory, often favoring a strategy of “the best defense of a good offense.” From this perspective, it’s a disaster to see NATO influence expand into lands once either dominated by Moscow — like East Germany — or directly ruled from it — like Poland (under the tsars) and Estonia (as late as 1991).

In former Soviet/Russian territories such as Ukraine or Georgia, Clement said, “if the perception is NATO or even the EU is making inroads — because they seem to see the EU as leading to NATO — they’re going to react.” That doesn’t mean conquering whole countries, he noted. Because NATO’s rules prohibit admitting any country with ongoing territorial disputes, all Russia has to do is contest a sliver of Ukraine (e.g. Crimea) or Georgia (South Ossetia and Abkhazia) to keep them perpetually out of the alliance.

Not all of Russia’s lost lands are created equal, however. “They will take risks for gain in Ukraine,” Bearden said. “They wouldn’t take risks to bring the Baltic States back in.”

“Ukraine (is) the most important country in the world from Russia’s perspective,” agreed Beebe. “They believe they’ve got the most to lose there.”

Ukraine holds a place in Russian hearts and minds that is hard to explain to Americans. Except for a period of tenuous independence in 1917-1920, Ukraine had been Russian territory since 1795. Eastern Ukraine, where Moscow is now waging a proxy war, fell under Russian control in 1657 (well before the United States existed). Even the name “Russia” comes from “Rus,” identifying the country with the medieval principality whose heartland lay in modern Ukraine and whose capital was Kiev (rather as if the entire modern US called itself “Texassia” and kept doing so even after Texas seceded). Putin himself invoked Kievan Rus in making his claim to Crimea. For a Russian nationalist like Putin, the idea that Ukraine does not belong to Russia is painful and humiliating.

The Fault’s Not In Our Stars

It’s also America’s fault, according to the often conspiratorial worldview of ex-KGB agents like Putin, Milton Bearden said. “All of the KGB officers I knew blamed us for everything that happened,” he said. In their “perhaps faulty” view of history, “it’s payback time for the United States.”

But it’s payback within limits, a secondary effort to their main push in what Russians call the near abroad. “They want to corral American power, counterbalance it,” said Beebe, not “destroy” it, which would open economic, geostrategic and even nuclear cans of worms Moscow can’t cope with.

“I don’t think that Vladimir Putin, who I think is a realist, wants to destroy us or our democracy, (though) they did meddle… and they will do it again if they can,” Bearden said. “They will continue to stir the pot, (but) I think they’re as amazed by what we’re doing to ourselves as perhaps we are.”

“I don’t think Putin seeks to destroy the US,” agreed Clement. “A lot of our internal domestic problems are in fact of our own doing, (though the Russians) have very skillfully exploited it.”

“I would submit today that the United States is going through a period of rather significant domestic problems, a crisis in confidence that is generated largely from within,” Beebe said. “We’re projecting many of those domestic problems and fears onto Russia.” In truth, we’re doing plenty of that damage to ourselves and by ourselves.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.