Rep. Randy Forbes: Don’t Break Ranks With Allies In Face Of China’s ADIZ

Posted on

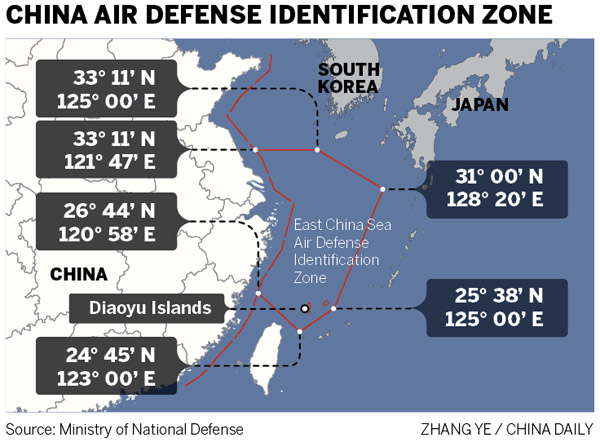

China’s new “Air Defense Identification Zone,” which covers both the Japanese-controlled Senkaku Islands — clamed as the Diaoyus by China — and the Korean-controlled Ieodo Island — claimed by the Chinese as Suyan Rock.

WASHINGTON: As the crisis over China’s self-declared “air defense identification zone” hits its tenth day with no signs of de-escalation, leading Republican lawmaker Rep. Randy Forbes questioned an apparent concession by the administration over commercial flights. Meanwhile, South Korea is contemplating expanding its own long-standing ADIZ to challenge China’s — but it might do so in a way that would cause conflict between Seoul and Tokyo as well. So while the US, Japan, and South Korea have presented a united front so far; they may not be able to keep it up as the stand-off drags on.

Commercial Flights Split US From Japan & South Korea

All three democracies have now flown military aircraft through China’s new ADIZ without complying with Beijing’s demand to file flight plans in advance and to communicate via radio once in the zone. The issue between the allies is whether commercial flights should follow China’s unilaterally declared rules (reprinted here on the FAA website).

The governments of Japan and, more quietly, South Korea have gotten their national airlines not to. The US State Department, however, just quietly reiterated the longstanding US policy that airlines should comply with all countries’ flight rules — which presumably would include the new ones put out by China, although State didn’t say so outright.

That ambiguity prompted a pointed inquiry by influential by Forbes, chairman of the House Armed Services subcommittee on seapower and leader of HASC’s outreach to Asia-Pacific ambassadors.

“The biggest thing for us is to make sure we get the facts,” Rep. Forbes told me in a phone call this afternoon. “We have had some media sources suggesting that the administration was telling private commercial airliners they need to file flight plans with the Chinese in compliance with their [China’s] announcement…. What I’m hoping to find out is they did not do that and they’re leaving it up to the airlines to do what they think appropriate.”

So what is the White House doing? Here’s what an anonymous administration official told reporters in Japan as I was speaking to Forbes: “There wasn’t a ruling by the FAA on the issue,” said the official. “Contrary to reports, the FAA did not issue guidance with regard to the Chinese NOTAM” — that is, the Notice to Airmen that Beijing issued laying out the rules for its new air defense identification zone. “What the FAA has done is simply reiterate longstanding practice that for the safety and security for passengers, US civilian airlines operate consistent with NOTAMs the world over,” the official said. “That is the practice or the policy that the FAA has the world over. There’s nothing specific to this ADIZ.”

“In terms of the US-Japan position on the ADIZ, there is fundamentally no daylight between us,” the administration official emphasized. “Nothing the FAA has done constitutes any acceptance or recognition of this [i.e. the Chinese zone].”

Nothing, that is, except for the timing: Just when our Northeast Asian allies are specifically ordering their airlines not to comply with China’s NOTAM, the FAA reminds US airlines that they should comply with everybody’s NOTAMs “the world over.”

“It seems to me Obama administration officials do not want to take the slightest risk that there would be an incident involving a commercial airliner,” said Bonnie Glaser, a leading Asia expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “But if in fact they have encouraged all airliners to comply, they have opened a crack between what the United States is doing and what Japan and South Korea are doing.”

There is certainly a case to be made for civilian airlines taking every possible precaution to avoid lethal mistakes. Call it the KAL 007 argument. China’s claims are questionable, but their aircraft are armed. In 1983, when Korean Airlines flight 007 strayed off course into Soviet airspace, the Soviets mistook it for a US spyplane and opened fire: 269 people died. In 1988, the US Navy cruiser USS Vincennes mistook an Iranian airliner for an attacker and shot it down: 290 people died. It’s one thing for a small number of military personnel to knowingly put their lives at risk to assert their nation’s rights: That’s part of their job. It’s very different to risk civilian lives by the hundreds.

Even Forbes made clear he didn’t want the US to order airlines not to comply, as the Japanese and South Koreans have. He just doesn’t want the US government to pressure them to comply. “It’s very important that the administration not be telling commercial airliners that they can’t fly over there without filing these flight plans,” he said. “That is something that the airlines should make the determination on.”

In other words, it’s not essential to have a unified front among the commercial airlines: It is essential to have a unified front among the three governments.

“I think the US did the right thing when it flew our [military] planes over there initially and I think we need to continue,” Forbes told me. But we can undermine our own position “if we start just complying with the Chinese requests or if we send out mixed messages to our allies.”

China’s trying to “exert a control I don’t think they’re entitled to” over international airspace, Forbes went on. (China’s rules are much more restrictive than those of other nations’ ADIZs). If you let any country make such a claim and then tell people to comply with it for safety’s sake, he said, you’re gradually ceding the freedom of navigation through the “global commons” — air, sea, space, and cyberspace — that is a central pillar of US policy.

Such concessions are especially dangerous with China, because its strategic approach is a combination of the children’s book If You Give a Mouse a Cookie and the old wives’ tale that if you raise the temperature slowly enough, you can boil a frog alive without it ever noticing. Beijing is patient, persistent, and relentless, always ready to take today’s small concession and turn it into the basis for another, larger claim tomorrow.

‘The Chinese have been rolling out a series of steps to put pressure on the Japanese, to force the Japanese to admit and acknowledge that a territorial dispute exists, and to compel Japan to come to the negotiating table” eventually, Glaser told me. “This is part of a longer-term strategy to control air and sea space in what they refer to as their near seas.”

South Korea’s Dilemma: Confronting China May Involve Offending Japan

Of the three democracies, it was South Korea that was closest to China before the current crisis, and its response to the zone was initially the mildest. In fact, last weekend, instead of working out a common approach with the US and Japan, Korea asked the Chinese to redraw the zone so it would no longer overlap Korean claims.

“This was an attempt to delink [Korea] from the US and Japan,” said Victor Cha, who holds the Korea Chair at CSIS. But instead of seizing the opportunity to split Korea from the other two democracies, China refused. The result? Seoul has started planning to expand Korea’s own air defense identification zone.

Here’s the embarrassment for Seoul: Their existing ADIZ, drawn up during the Korean War by the Americans, does not actually cover all the waters Korea claims. At issue with Beijing is what the Koreans call IeodoIsland but English speakers call Scotora Rock — it’s not actually an island but a reef just below the surface of the water. China claims it as Suyan Rock.

Here’s Seoul’s dilemma: Ieodo is already within Japan’s ADIZ. Japan doesn’t claim the rock as its own territory, so Korea’s dispute is currently only with China — but if Korea extends its ADIZ to overlap with Japan’s, it may become a three-sided quarrel. (Japan and South Korea do have a dispute over who controls the Dokdo/Takeshima Islands, but China’s not involved there).

Unlike China, though, Korea is at least talking to people before deciding whether and how far to extend its air defense zone. “Although the Korean government’s under political pressure [domestically], they’re cautious,” said Ellen Kim, assistant director of the Korea program at CSIS. “I think the Korean government wants to coordinate this issue with the United States and Japan.”

Part of the problem here is that China’s declaration took everyone by surprise. “The three countries never had a chance to coordinate this issue at all,” Kim told me. “That’s part of the reason why the three countries are having a difficulty coordinating their responses.”

But the deeper problem is a profound distrust between Koreans and Japanese that dates back to at least 1876, when the Japanese Navy bullied Korea into opening its ports to Japanese trade. Japan annexed Korea in 1905 and ruled it with increasing brutality until the US and Russia moved in 40 years later at the end of World War II.

Relations between Seoul and Tokyo are currently pretty icy. In a poll conducted just this September, 62 percent of South Koreans said they considered Japan a military threat.

But in the same poll, 58 percent of South Koreans said the two countries should hold a summit — something Korean President Geun-hye Park has pointedly refused to do with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. 60 percent said the two countries need a deal to share military intelligence — a deal that was almost reached two years ago but which Seoul pulled out of at the last minute.

Lately, said Cha, there has even been significant “softening” in Seoul’s official stance. “Just last week,” he told me in an email, the Korean Foreign Minister laid out what Cha called “boilerplate conditions” under which Korea would agree to Japan increasing its military cooperation with other countries. That kind of “collective self-defense” is something that the Japanese have historically considered against their pacifistic constitution, but Prime Minister Abe is trying to get some legal maneuvering room — and the Koreans are signaling their willingness to discuss it. “So,” said Cha, “that gives us some room for the two to begin consultations.”

To date, the common danger pushing South Korea and Japan together hasn’t been China: It’s a nuclear-armed and increasingly erratic North Korea. But now China has managed to offend both Seoul and Tokyo at once.

While the US has tried to get South Korea to take the Chinese danger seriously, that China has now gone ahead and actually taken “reckless” and “aggressive” action “is more persuasive than [us] just arguing they might take that particular action,” Rep. Forbes told me.

“If we do the right things, I think we can also show the Chinese and the rest of the world that they really don’t have the ability to enforce some of these provisions,” Forbes said. “You can scream, you can shout, you can beat on podiums, but, all of a sudden when it comes to put up or shut up… if we play this right, the Chinese will come out looking weaker.”

Updated 10:25 pm with Victor Cha’s comments.

Corrected 11:00 am Wednesday: It was the State Department that issued the reminder to commercial airlines to comply with NOTAMs worldwide. An earlier version of this article stated incorrectly it was the FAA.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.