Raytheon Gets $636M For Missile Defense – But Where Are The Lasers?

Posted on

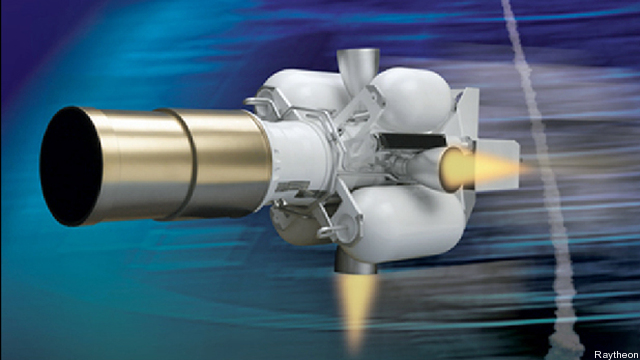

“Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle” is arguably the most awesome name on record for a Pentagon program. Technologically, the Raytheon-built EKV is pretty impressive, able to hit an incoming missile head-on at over 15,000 miles per hour.

Some background: The Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle is the business end of the missile defense system now based in Alaska and California, the guided warhead that separates from the booster rocket to seek out and destroy enemy missiles in space (hence “exoatmospheric”) before they hit the US. On Monday, at the Farnborough Air Show in the UK, Raytheon executive Wes Kremer announced that the company had signed a new $636 million, seven-year contract to provide EKVs to Boeing, the lead contractor for ground-based missile defense.

Raytheon has been the sole supplier of EKVs since 1998, so long that the EKV has been redesigned both to improve performance and to replace components that became obsolete over the long production run. Two powerful Republican Senators, Jon Kyl and Richard Shelby, have suggested recently that it’s time for a more modern, more compact design that could fit multiple EKVs on a single rocket booster — a “multiple kill vehicle” approach that Lockheed Martin was working on before then-Secretary Robert Gates cancelled it in 2009. So while the new Boeing contract wasn’t a surprise, but more of a routine renegotiation of a longstanding deal, it still represents a $636 million vote of confidence in Raytheon.

An article about the deal on the website Business Insider enthused that the Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle was the realization of Ronald Reagan’s “Star Wars” dream. It’s not. What Reagan wanted was – in the immortal words of Dr. Evil – frickin’ laser beams. While the Gipper was an actor rather than a scientist, his reasoning was not Hollywood logic but rational physics.

All current missile defense systems, from the Patriot to the EKV, work by shooting down the incoming missile with another missile, a task famously compared to “hitting a bullet with a bullet.” The problem is that it’s a lot harder to hit a hurtling projectile than, say, a warship, an airbase, or a city, so the interceptor has to be a lot more accurate and maneuverable than the incoming missile it’s trying to shoot down – which makes it more expensive.

A recent report by the influential Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments calculated America’s various missile defense systems cost anywhere from $3.3 million to $15 million a shot – and it typically takes two shots to be sure of a hit, so double that figure – compared to $1 to $3 million for a souped-up Scud. Even at these rates, the US can probably afford to buy more defensive missiles than impoverished North Korea can buy offensive missiles, but China or even Iran can simply buy more missiles than we can ever hope to counter. That’s what CSBA’s experts call a “cost imposition” dynamic, and we’re the side the costs are being imposed on.

CSBA’s solution? It’s the same as Reagan’s: lasers. A solid-state laser is expensive to build, but once it’s built, you can keep firing as long as you have power. Instead of expending a $15 million missile with every shot, hit or miss, you’re just using electricity.

“We’re currently on a path where an enemy can impose costs against us,” shooting our $15 million missiles at their $1 million ones, said the report’s lead author, Mark Gunzinger, in a conversation with Breaking Defense. “If we can counter that million-dollar missile with a $10 or $20 beam of light, that’s cost imposition against them.”

Gunzinger doesn’t want to abandon interceptor missiles (“kinetic” weapons) in favor of lasers (aka “directed energy”): “You’ve got to have both,” he said. “But right now kinetics is the only part of that spectrum [of options] that we’re seriously funding. Directed energy is still a set of technology development efforts that have not transitioned to real-world capabilities. The point is, they’re at the point where they could transition given enough support.”

Will that support be forthcoming? In an era of tight and uncertain defense budgets, that’s not likely.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.