Proxy War Protocols: How To Make Syrian Opposition Work

Posted on

If the United States arms the so-called “moderate Syrian opposition” to try and overthrow both ISIL and Bashar al Assad, president of Syria, will it work?

A close look at the United States’ long and checkered history backing proxy forces reveals a very mixed record when we arm surrogates. The ledger includes historic fiascos such as the CIA’s 1963 Bay of Pigs campaign designed to overthrow Fidel Castro in Cuba in 1963 with a ragtag band of exiles; the dirty wars of the 1980s in Central America that entangled the Reagan administration in scandal; and the more recent campaign to help rebels unseat strongman Muammar Gaddafi in Libya in 2011, leaving that country in the grip of a civil war.

But the record also includes notable successes such as U.S. support for the Afghan mujahedeen in their fight against the Soviet army in the 1980s, a campaign that drove the Red Army out of Afghanistan and contributed to America’s victory in the Cold War; a covert campaign the U.S. and its NATO allies mounted in the mid-1990s to arm, train and assist with military advisers a Croatian army that ultimately pressured Bosnian Serbs to sit down and negotiate a peace settlement, thus helping end the bloodiest conflict in Europe since World War II; and a more recent U.S. campaign to arm, train and assist with airpower an African Union force that has driven the Al Qaeda affiliated Al- Shabab terrorist group out of most urban areas in Somalia.

Former CIA officials and experts say there are lessons from that history that should inform the Obama administration’s current campaign to “degrade and defeat” the hybrid terrorist army called the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL). The record points to limitations and the potential for unexpected blowback from proxy wars, they note, but it also indicates that when the threat to the United States or its interests is compelling, and Washington is unwilling to commit decisive U.S. military force, proxy forces can prove useful tools.

Choose Your Enemy Well

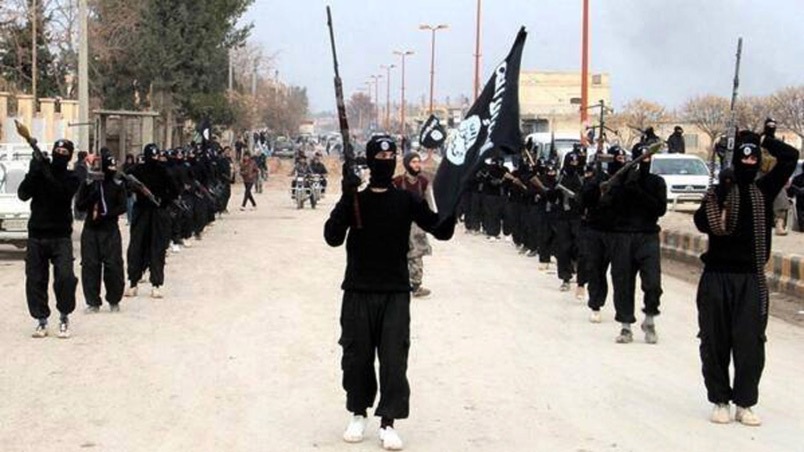

The inherent limitations and messiness of proxy wars dictate that they should only be waged when the threat is compelling. There is a general consensus among national security experts that Obama had little choice but to act against ISIL last summer. Absent U.S. military action, virulently anti-Western ISIL fighters had captured roughly a third of the territory of Syria and Iraq and were poised to carve a so-called caliphate out of the carcass of both of those failed states.

This threatened the United States’ Kurdish allies in northern Iraq and the Iraqi capital of Baghdad. ISIL’s mass executions of prisoners, ethnic-cleansing of minority populations, sexual slavery of captured women, and beheadings of Western hostages to include two American journalists, helped to drive home the urgent nature of the threat.

“It should be patently obvious that becoming involved in another Middle East conflict and sending the U.S. military back to Iraq was absolutely the last thing President Obama wanted to do, which is an indication of just how profound a threat ISIS has become,” said Bruce Hoffman, a counterterrorism expert at Georgetown University and co-editor of the new book, “The Evolution of the Global Terrorist Threat: From 9/11 To Osama Bin Laden’s Death.”

“ISIS is the uber-Al Qaeda,and the truest manifestation of Osama bin Laden’s vision of a war between Islam and the West,” said Hoffman. “We should be realistic in our expectations of how long this campaign is going to take, and how hard it will be, but doing nothing while ISIS continued to gain strength and territory was not an option.”

Show a United Front

A close corollary of the first protocol is uniting the White House and Congress against a common, well-understood enemy. U.S. support for Afghan mujahadeen lasted many years during the 1980s, for instance, largely because both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue were united in contesting the Soviet invasion and its brutal subjugation of Afghanistan. By contrast the Reagan administration’s proxy war supporting the “contra” rebels against the communist Sandinista regime in Nicaragua was opposed by many Democrats in Congress, who passed legislation barring such support. Reagan’s efforts to get around those legal restrictions led to the worst crisis of his tenure, the Iran-Contra scandal involving secret arms transfers.

As the former CIA station chief in Pakistan in the 1980s, Milt Bearden was in charge of the U.S. campaign to arm the Afghan mujahedeen to fight the Soviets. “You could argue that the Afghan war was the most successful U.S. proxy campaign because everyone from the Reagan White House, to Congress and even the media were all united in their desire to punish the Soviets for their brutality in Afghanistan, to the point that I had too much help at some points, with people offering to give me weapons that I didn’t really want,” Bearden said in an interview. “By contrast many Democrats in Congress were dead set against arming insurgent groups in Central America like the Contras, and they were looking for any excuse to kick Reagan’s butt for his support. Even [late Texas Congressman and infamous mujahedeen champion Rep.] Charlie Wilson refused to lift a finger for the contras because they were so controversial.”

Beware a Search for `Moderates’

Recent news that Al Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate the al-Nusra Front had joined forces with ISIL in an offensive that routed U.S.-backed rebels in northern Syria points to another truism of proxy wars: extremists tend to rise to the top in civil wars, and the search for “moderate” rebels to back can prove Quixotic. Lines between “good guys” and “bad guys” often blur.

“I worked with a lot of so-called ‘moderates’ during the Afghan war, and what I found was they worked the Capital Hill cocktail circuit very well, but when we gave them weapons within days we’d find those weapons up for sale in the arms bazaars,” said Bearden. “When we gave the Muslim fundamentalists weapons, they used them. The idea that ‘moderates’ win revolutions or make good insurgents is a myth.”

In the current conflict the United States cannot side with one Al Qaeda offshoot against another, nor condone extremist behavior. And the lack of viable “moderates” almost certainly will require that the U.S. military adopt an “enemy of my enemy is my ally” ethos,” at least in the short term. Already U.S. commanders have launched airstrikes and delivered weapons to Syrian Kurds aligned with the Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, which both Turkey and the U.S. label a terrorist group.

At least initially, we have also put up with Iranian-backed Shiite militias in Iraq, which were crucial to turning back ISIL’s summer offensive towards Baghdad as Iraqi forces crumbled. Retired Marine Corps Gen. John Allen, chosen by Obama to head the international anti-ISIL coalition, has also reached out to Sunni tribes that have aligned themselves with ISIS out of fear of the group and their hatred for the repressive Shiite-led government in Baghdad. Their eventual defection from the ISIL alliance could prove the lynchpin of the Iraq campaign.

Boots Needed on the Ground

In the recent Brookings Institution report “Building a Better Syrian Opposition Army,” former CIA Middle East analyst Kenneth Pollack argues that a credible Syrian rebel force of two or three combat brigades will not only need U.S. heavy weapons, airpower support and training, but also “a heavy U.S. advisory complement to further ensure success.” The template he proposes draws on U.S. support for the Croat army in 1995, and the Pakistani military’s training and support of the Taliban who seized Afghanistan in 1994.

“The recently leaked CIA report [noting failed proxy campaigns] focused on instances where the United States provided only weapons and training to indigenous groups, with no direct U.S. air support or combat advisers, which can make a huge difference,” Pollack said in an interview. “The best model is Bosnia, where the United States and NATO helped create and then advised and assisted the Croat army, which crushed the Serbs until they were ready to come to the negotiating table. At that point we insisted that [former President of the Serb Republic and war criminal Radovan] Karadzic had to go. Something similar needs to happen with Assad in Syria.”

Currently there are roughly 1,400 U.S. train-and-assist personnel in Iraq, but the Pentagon has announced plans to more than double that number in anticipation of a spring offensive by Iraq Security Forces. Current plans also call for essentially doubling the number of Iraqi Security Forces being trained and advised from three to six divisions (including both ISF and Kurdish peshmerga units). When those forces go on the offensive against dug-in ISIS forces in urban settings like Mosul next year, Gen. Martin Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, has indicated that the need for on-the-ground U.S. advisers and air controllers will likely increase.

“I think the best model is what our Special Operations Forces and CIA paramilitary accomplished when they married U.S. airpower to the Northern Alliance fighters in 2001, and rapidly toppled the Taliban in Afghanistan. That’s where I think we’re headed,” said retired Maj. Gen. Paul Eaton, who led the training of Iraqi Security Forces. Currently U.S. air forces only conduct a handful of strikes a day against ISIS forces in Iraq and Syria, he notes, compared to more than 130 a day during the 1999 Kosovo Air War. “That may suggest inadequate ‘target generation’ on our part, which sooner or later will lead to frustration and the deployment of more SOF and Air Force forward air controllers.”

Don’t Walk Away

If there is a common thread that runs through the history of U.S. proxy wars, it is a tendency of Washington to walk away both militarily and diplomatically once its tactical goals are either achieved, or else diverge from those of its local proxies. Perhaps most famously, Washington essentially washed its hands of Afghanistan once the Red Army retreated, leaving a power vacuum filled by a civil war among warring factions and paving the way for the emergence of the Taliban and Al Qaeda. The United States arguably turned away from Afghanistan again in 2003, when the Bush administration turned its attention to Iraq before nascent Afghan governing institutions had a chance to take root.

That cycle repeated in Iraq in 2011, when the Obama administration failed to reach agreement to leave a residual U.S. force there to continue nurturing Iraqi Security Forces and to curb the sectarian impulses of the Baghdad government. It may come full circle in Afghanistan in 2016, when the Obama administration plans to remove all U.S. military forces.

The United States could be repeating those mistakes if it focuses just on the tactical fight against ISIL, and fails to follow through with the diplomatic heavy lifting necessary to achieve political outcomes in Baghdad and Damascus that end the civil wars: namely a power-sharing arrangement in Iraq that somehow stitches Sunnis, Shiites and Kurds into a single national identify; and the removal of Assad in Damascus as a prerequisite to reconciliation between its warring factions.

“Assuming we’re not going to stay around and hold the hands of our proxies forever, these conflicts always raise the a question of fragile loyalties and shifting alliances,” said Paul Pillar, a former deputy director of the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center, and a senior fellow at Georgetown University’s Security Studies Program. That shouldn’t rule out limited, well-calculated uses of U.S. military force in instances where our objectives align with those of our proxies in ways that can accomplish some good, said Pillar. “But we should continually remind ourselves that the outcomes of these conflicts are more dependent on the politics in Baghdad and Damascus than they are on whatever ordnance the U.S. decides to drop in those countries.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.