Pentagon To Retire USS Truman Early, Shrinking Carrier Fleet To 10

Posted on

UPDATED with additional comment WASHINGTON: Amidst rising anxiety over whether the US Navy’s thousand-foot-long flagships could evade Chinese missiles in a future war, the Pentagon has decided to cut the aircraft carrier fleet from 11 today to 10.

By retiring the Nimitz-class supercarrier USS Truman at least two decades early, rather than refueling its nuclear reactor core in 2024 as planned, the military would save tens of billions on overhaul and operations costs that it could invest in other priorities. But the proposal, part of the 2020-2024 budget plan due out mid-March, is sure to inspire outrage on Capitol Hill.

“I can’t imagine this will go over well at all,” one Hill staffer told me. We’re pressing congressional leaders for official responses, but the Pentagon decision seems to have blindsided them entirely. Navy officials have declined to comment on the forthcoming budget.

There’s tremendous resistance to overcome. Over the years, congressional carrier advocates have

- enshrined a minimum force of at least 11 carriers in law,

- repeatedly called for an increase to 12 flattops, a goal President Trump once publicly embraced; and

- resoundingly defeated the last attempt to cancel a mid-life overhaul, back in 2014–2015 when the Obama Administration — admittedly less popular with congressional Republicans than Trump — tried to retire the USS George Washington early.

Rep. Joe Courtney, chairman of the House seapower subcommittee, poses proudly aboard the USS Truman.

As the George Washington saga showed, “the mid-life overhaul has been used as a bargaining chip for a larger budget in the past,” said Jerry Hendrix, a retired Navy captain turned analyst. With Truman as with Washington, he said, “I doubt the Congress would allow it to go through.”

The decision to cancel the mid-life overhaul was first reported by Washington Post columnist David Ignatius yesterday evening, as a one-sentence aside in a larger story, without naming the carrier. Breaking Defense has confirmed the ship is the Truman and that cancelling the overhaul would effectively retire the ship 20 to 25 years early, shrinking the carrier fleet from 11 to 10 in the mid-2020s.

Over time, the Hill source said, as retirements outpace new construction, “not only would the fleet not reach 12 any time over the next 30 years, the carrier force would number nine ships for a majority of the 2040s.”

UPDATE “The decision to skip the Truman’s RCOH [Refueling & Complex Overhaul] was part of the deal to fund two new carriers,” said former deputy defense secretary Robert Work. “We would end up with a smaller, but younger fleet…. Secretary [Bob] Gates made a decision to move to five-year [gaps between carriers], which would ultimately result in a 10-carrier fleet around 2040. So we are still on that path.”

UPDATE CONTINUES “A 10-carrier, nine Carrier Air Wing force sounds about right to me,” said Work, who pushed for the Pentagon to embrace new strategies and technologies against high-end threats, “as technological uncertainty over the carrier’s vulnerability continues to be high.” (More on that debate below).

Billions in Savings – At What Cost?

Ignatius mentioned an estimated $4 billion in savings, but the real figure over time is likely to be much higher. The overhaul itself costs $6.5 billion and operating the carrier thereafter costs about $1 billion a year. So total savings could exceed $30 billion, albeit spread out over decades.

Truman entered service in 1998 and was built to serve for 50 years, but like all nuclear carriers, it requires regular maintenance, periodic upgrades, and a major overhaul at mid-life when its reactor core runs out of uranium. The ship was scheduled to go into the Newport News shipyard in 2024 for a mid-life Refueling & Complex Overhaul (RCOH) ending in 2028. That’s beyond the five-year budget plan about to be released, which therefore won’t include the vast majority of the savings from the cancellation. (That probably accounts for Ignatius’s estimate being too low).

Cancelling the overhaul would let the reactor run down: Exactly how fast depends on exactly how hard the Truman has used it over the years, Hendrix told us, and on how hard it’s run in the future. It would force the ship’s retirement at some point in the mid to late 2020s, two decades ahead of the expected date of 2048.

Losing the $6.5 billion overhaul would be a major blow for Newport News, the only shipyard on the planet capable of building a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. Having thrived during the Reagan buildup, Newport now struggles to cover its massive overhead and retain highly skilled workers such as nuclear welders.

That said, it would be even more painful to cancel construction of a new Ford-class carrier, valued at over $12 billion. (That’s the total price to the government, not just payments to Newport News, under a new contract that saved $4 billion by bundling two ships together in a single buy). It’s also possible for Newport to shift at least some workers to its rapidly growing nuclear submarine business, which some experts had worried would overwhelm the yard as the Navy ramped up production of both Virginia-class attack boats and the new Columbia-class ballistic missile sub.

“I don’t want to speculate on what will be in the President’s budget proposal,” said Beci Brenton, a spokesperson for the Newport yard’s owner, Huntington-Ingalls Industries. “I can tell you that the mid-life refueling overhaul and maintenance availability of a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier produces a recapitalized carrier capable of supporting current and future warfare doctrine and continuing to operate as the centerpiece of our Navy fleet and our national defense for another 25 years.”

“An RCOH [Refueling & Complex Overhaul] is an extremely complex engineering and construction project which involves more than 680 suppliers from 40 states providing material and services critical to the overhaul process,” Brenton continued, a point that will certainly resonate in Congress. “The stability of this industrial base is critical to our ability to continue to build and maintain the navy fleet our Navy and nation needs.”

“The three major components of [the shipyard’s] business base are new carrier construction, carrier RCOHs, and submarine construction,” said Ronald O’Rourke, a leading naval expert with the Congressional Research Service, which advises legislators. “Not doing the CVN-75 [Truman] RCOH would result in a roughly four-year dip in the RCOH component of that business base, and a resultant dip in employment… At the same time, however, [the yard] could experience an increase in the volume of its submarine-construction work, which might offset to some degree the dip in RCOH work and employment.”

Strategic Stakes

Not overhauling of old carrier you already have may seem a less efficient way to cut costs than just not building a new carrier at all. But O’Rourke said cancelling a carrier outright could make it much harder — even impossible — to build any carriers in the future.

Cancelling an overhaul is much more manageable, though hardly painless. “If you want to reduce the size of the carrier force in the shorter term, this is often the way that people have discussed doing it,” he said. “The principal alternatives would be to forego the construction of a new carrier, stretch out the intervals for building new carriers, or retire early a carrier that has already received an RCOH.”

UPDATE “If you want to maximize the savings from cutting a carrier, then the two times to do it are to cut it before it is built or just before it goes into mid-life overhaul,” agreed CSIS expert Todd Harrison. “Cutting a new carrier from being built is difficult to do because of the impact on the industrial base, so realistically all you can do is gradually slow the rate at which new carriers are built, which spreads the savings far out into the future. If you want to maximize near-term savings, then cutting an overhaul is the way to do it.”

The impact on the industrial base — Newport News and its vast network of suppliers — is critical. Cutting or even slowing production of new carriers would disrupt the shipyard so badly that future ships you did build would be much more expensive. Raise the price of the next ship too high, O’Rourke said, and you effectively lose the option to build a supercarrier ever again.

“That part of the defense industrial base must be preserved as long as we continue to build supercarriers,” Hendrix told us. But do we want to?

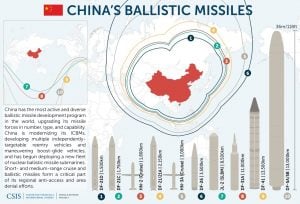

UPDATE “You shouldn’t cut a carrier just to save money: It should be part of a broader strategic rebalancing of the force, and that’s what it sounds like this is,” Harrison said. “Carriers are increasingly less useful against adversaries that have anti-ship missiles with ranges greater than the range of strike aircraft on the carrier” — such as Russia and China.

Types and ranges of Chinese ballistic missiles (Graphic by Center for Security & International Studies) (Click to expand)

The Navy has argued carriers are inherently flexible assets, mobile airbases with plenty of room to add new equipment or new airplanes to counter future threats. But as far as current budget plans go, Hendrix noted, the carrier will rely on relatively short-ranged fighters like the F/A-18E Super Hornet and the stealthy F-35C Joint Strike Fighter for its offensive firepower. That requires it to close to well within the range of Chinese land-based anti-ship missiles so the fighters can reach their targets. (Fighters can refuel in mid-air, but the slow, bulky tankers are extremely vulnerable and can’t come any closer to enemy airspace than the carriers themselves). Hendrix and many other experts have long advocated for longer-range aircraft, both manned and unmanned, to keep the carrier relevant and survivable.

UPDATE If you retire Truman, you could “theoretically” disband one of the Navy’s nine current carrier air wings, said retired Navy commander Bryan Clark, now with thinktank CSBA. (Traditionally, there’s one less wing than the number of carriers, since at any given time one ship is in overhaul and unavailable). But Navy aviation is so short of personnel and flyable fighters that it would probably just reallocate the dissolved wing’s assets to fill holes in the other eight — improving readiness but not saving much money.

UPDATE CONTINUES “Taking the savings and putting it into some other part of the Navy is probably not the right answer,” Clark said. “What they should do is put that money back into readiness and future capabilities of the air wing, [especially] the development of a new set of airplanes that will be more relevant to the future competition, like unmanned systems that are more survivable.”

UPDATE CONTINUES The Navy once planned to develop a long-range, carrier-launched strike drone, UCLASS, but it downgraded the program to just a refueling tanker with some scouting capabilities, the MQ-25.

“If the Navy continues to fail to invest in a new air wing that can do a long range strike,” Hendrix told me, “then the government may decide to stop building carriers in order to free money for other platforms that would be more relevant for the threat environment” — such as smaller surface ships and unmanned craft — “in which case stopping new construction would be the best path towards a drawdown of the carrier force.”

But that’s not a bridge anyone is willing to burn, just yet.

Paul McLeary also contributed to this story.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.