Pentagon Eyes Military Space Station

Posted on

Star Trek’s Deep Space Nine manned space station

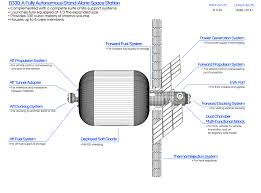

WASHINGTON: The Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit wants options for an unmanned orbital outpost to support space experiments and operations — a logistics hub that might even grow, DIU’s solicitation suggests, to a larger manned space station.

DIU, which is charged with tapping non-traditional commercial companies for innovative technologies to meet Pentagon needs, issued a solicitation last week that gives interested vendors until July 9 to propose a “solution… for a self-contained and free flying orbital outpost.” The platform is to support “space assembly, microgravity experimentation, logistics and storage, manufacturing, training, test and evaluation, hosting payloads, and other functions.”

While the near-term requirements are obviously aimed at prototyping an autonomous, robotic mini-space station to house experimentation, the “future desired capabilities” listed in the solicitation are much farther reaching. They include the capability to dock with unmanned and manned spacecraft and, even more surprisingly, “human rating.”

Human-rating is short-hand for a set of requirements developed by NASA and the Federal Aviation Authority (which licenses launch and re-entry of commercial spacecraft) to ensure the safety of astronauts aboard a spacecraft. These include things like special insulation to protect crew from extreme temperatures and radiation.

Even though the concept may be a long shot in DoD thinking, the fact that DIU is even considering the idea of a military presence in orbit is a pretty big deal. The idea will no doubt will be controversial if significant funding starts pouring into exploring it.

While the 1967 Outer Space Treaty technically does not prevent a military space station, manned or unmanned, it does prevent military operations and bases on celestial bodies such as the Moon or asteroids. It also guarantees freedom of “peaceful” use of outer space for all. US adversaries, as well as many allies, already are nervous about US intentions in space as the Congress debates President Donald Trump’s Space Force proposal. So the thought of space-based American troops is likely to raise concerns.

Before anyone gets too excited about a future US version of Star Trek’s Deep Space Nine, the baseline requirements for Orbital Outpost — including an 80 kilogram payload capacity and and internal volume of 1 meter cubed — are not even close to being able to accommodate humans.

“The thing is too small, 1 m cubed, and low power to do anything remotely human-rated,” said one space scientist.

One Air Force space official agreed, adding “I think the kicker is the 0 to 1 atmosphere pressurization. If DIU will accept vacuum or near vacuum, it won’t be able to support life at all, without some extensive upgrades. In short, this platform would be small, dark, cold, and without any life support!”

Indeed, Col. Steve Butow, director of DIU’s Space Portfolio based in Silicon Valley, says that DIU’s chief interest is in autonomous and robotic capabilities on orbit. “In short, we are casting a wide net for commercial solutions that can meet the basic needs described in the first part of the solicitation (autonomous/robotic, etc),” he told me in an email today.

He noted: “With respect to on orbit manufacturing, our DoD Partners are more interested in the ‘how’ rather than the ‘why’. Many of the autonomous capabilities proposed in supporting on-orbit manufacturing have dual use applications for national security and defense. One example of that is logistics.”

There are a number of commercial companies that have been exploring on-orbit assembly and manufacturing, including 3-D printing — primarily for future commercial uses and for NASA.

NASA since 2017 has hosted a 3-D printer aboard the International Space Station (ISS) made by commercial startup Made in Space. Made In Space didn’t return an email asking for comment by publication time.

NASA also is sponsoring a number of on-orbit experiments such as the Tethers Unlimited’s Refabricator payload, recently launched as part of DoD’s Space Test Program-2 mission (STP-2) on SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy. The Refabricator “combines a plastic recycling system with a 3D printer to enable astronauts to recycle plastic waste into high-quality 3D printer filament, and then use that filament to fabricate new parts, medical implements, food utensils, and other items that the astronauts need to maintain their spacecraft and perform their missions,” according to the company’s website.

Rob Hoyt, CEO of Tethers Unlimited, said his company intends to bid for Orbital Outpost, and is currently working to align DIU’s interests with the company’s own interests. “We are working on a modular approach to start out small and address some of those opportunities, and that then can be built up over time by adding more modules,” he said. Tethers Unlimited’s products largely target small satellites and cross a wide range, from software-defined radios to a small robotic arm.

Further, there are 28 corporate members involved in Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) CONFERS consortium developing industry best practices for on-orbit servicing activities. These firms range from established space players like Airbus to startups such as UK-based Effective Space that intends to use drones to help satellites station-keep (maintain their orbital parameters after fuel has run out.)

William Bolton, head of marketing and business development for Altius Space Machines, a Colorado-based startup that is part of the CONFERS consortium, said his firm is “evaluating” whether to bid or not for Orbital Outpost, given that the company has not traditionally looked at DoD as a customer. Still, as Altius is developing satellite servicing vehicles, interfaces and hardware, Bolton said the call for proposals is interesting.

On the other hand, Butow said DIU also didn’t want to cut off possible interest from vendors with “non-traditional or disruptive approaches” to the Orbital Outpost effort. He explained: “We know that a number of companies are working on solutions that may dock or interface with the International Space Station. … We simply did not want to exclude any of those solutions if one proves viable for our needs.”

NASA on June 21 issued a request for proposals (RFI) calling for habitable modules that can attach to the ISS and provide accommodations for tourists, or other commercial activities such as manufacturing or biotechnology experiments.

For example, companies that might be interested in Orbital Outpost could include Bigelow Aerospace, which is developing a number of inflatable habitats for use in orbit and on the surface of the Moon. Bigelow’s BEAM (Bigelow Expandable Activity Module) docked with the ISS in 2016, and will remain on orbit until 2020.

However, several military space experts cautioned that habitat concepts like Bigelow’s B330 would most likely be way too expensive for DIU’s small purse. The Pentagon’s fiscal year 2020 budget request included $29 million and change for DIU. Human rating of spacecraft is not an easy or cheap endeavor — as both SpaceX and Boeing have discovered in their (delayed) efforts to get their spacecraft certified by NASA to carry astronauts to the ISS.

Bigelow did not return a call requesting comment by publication time.

Still, the solicitation lists human rating among its “desired future capabilities” (emphasis mine) that could be “available as options for initial or future implementation.” This does not seem to indicate simply that these are ‘what-the-hell’ options, but capabilities someone in DoD might actually want. Further, there is a cadre of futuristic space thinkers who long have been arguing that a military presence on-orbit will be needed as commercial activities such as asteroid mining and space-based manufacturing become economically viable businesses.

Peter Garretson, former director of Air University’s forward-thinking Space Horizons Task Force, tells me: “If private citizens will be in space, then it makes sense for uniformed guardians to follow…and perhaps help lead and enable that desired future by retiring risk.”

Other interesting capabilities on that list include several that suggest the possibility of military space stations in farther-out orbits such as geosynchronous orbit or even in cislunar space, including:

- Servicing or re-provisioning to extend flight operations for a longer duration

- Orbit transfer

- Radiation hardening for beyond LEO applications

While just a few years ago, anyone proposing any military activities in cislunar space would have been giggled out of town, the future-oriented Air Force acquisition chief Will Roper has talked about doing cislunar space object tracking and former director of the Space Defense Agency (SDA) Fred Kennedy had developed an architecture that also included cislunar object tracking and even potential weapons-carrying Advanced Maneuvering Vehicles for rapidly “delivering effects” all the way out to the Moon. (Although the future of that proposed architecture is now in question following Kennedy’s departure and a likely re-think of priorities by DoD Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Mike Griffin who oversees SDA.)

A May 30 study on the US space industrial base by AFRL and DIU (of which Butow was an author) says that in the mid- to long-term (5 years and beyond) military activities will be driven by the “need to expand the locations and operations of critical assets into cislunar space to limit adversaries’ abilities to detect and attack these assets and to enhance ours and our adversaries ability to apply force through, from and in space;” and by the need “to establish the required infrastructure to return and establish a permanent US presence on the Moon and beyond.”

According to the DIU solicitation, bidders for the Orbital Outpost award will have to demonstrate that they can put their prototype station concept in LEO “within 24 months of award and have guidance, navigation and control for sustained free-flight operations. Favorable characteristics include modularity and scalability.”

While it does not provide a funding level, it does note that the Orbital Outpost effort will be multi-phased. The first phase will include engineering and design work. The subsequent phases will focus on the fabrication and test of the prototype, based upon the availability of fiscal year 2020 funding.

So marines patrolling space-launch corridors from an orbiting station, or airmen suiting up to repair spacecraft docked at a cislunar service station, are probably a long way off — but maybe they’re not just science fiction.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.