‘Optionally Piloted’ Aircraft Studied For Future Vertical Lift

Posted on

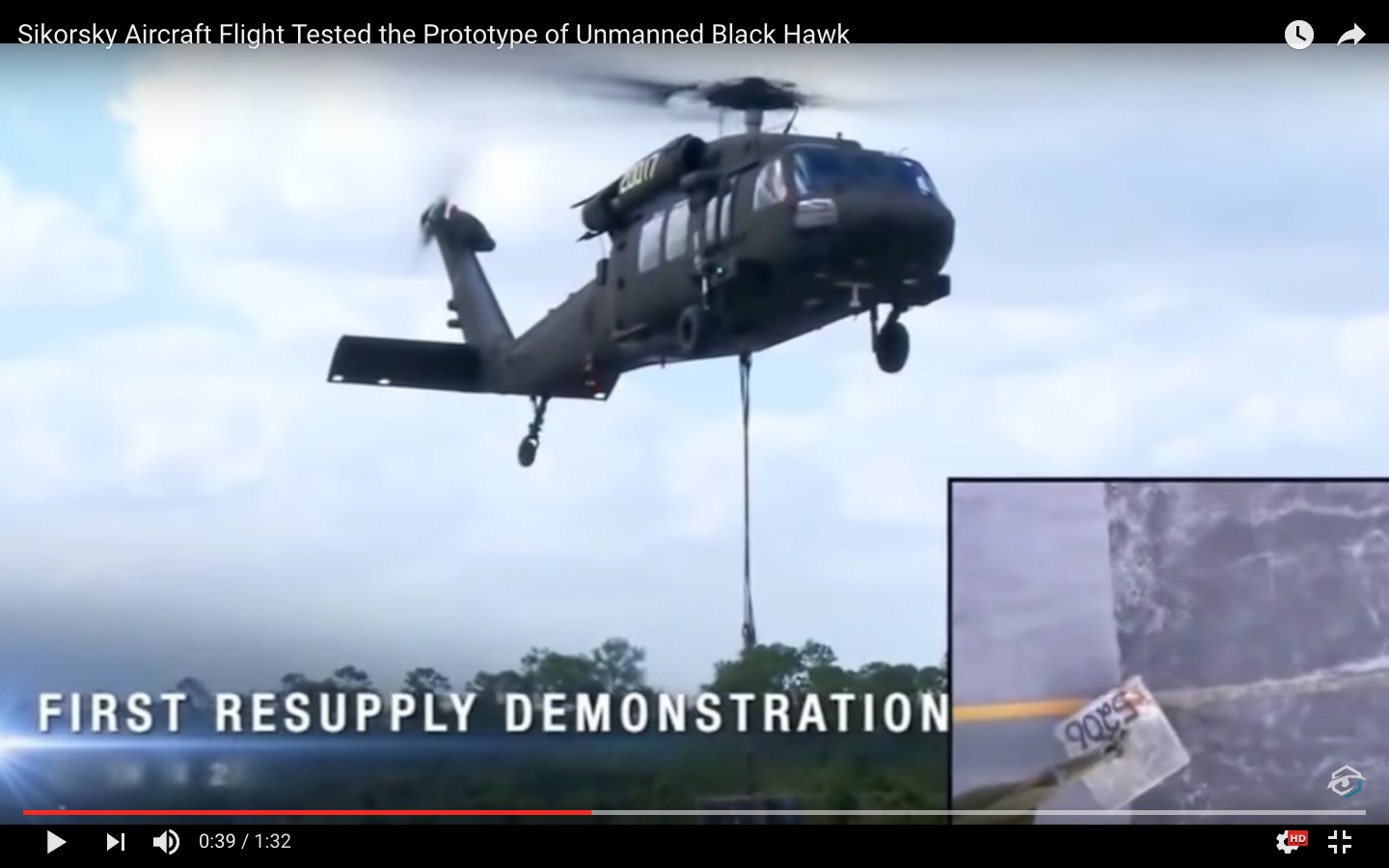

Sikorsky’s experimental “optionally manned” UH-60 Black Hawk

WASHINGTON: The military wants to replace a host of current helicopters with aircraft that not only fly much faster, but can fly without a human pilot. The Army-led Future Vertical Lift program will study whether FVL should be an “Optionally Piloted Vehicle,” capable of accommodating a pair of highly-trained human pilots for complex combat missions or of flying with an empty cockpit for routine supply runs.

Senior officers have already expressed public enthusiasm for the idea. Lt. Gen. Jon Davis, deputy commandant of the Marine Corps for aviation, told Breaking Defense last month that making FVL “optionally manned/unmanned,” depending on the mission, “has great potential.” Lt. Gen. Mike Murray, Army deputy chief of staff for program development, told Flight Global last week that he could “easily see” unmanned or, more likely, optionally manned rotary-wing aircraft in the future. But this is the first we’ve heard of a serious effort to study whether and how to actually do it.

“We’re shaping the study now,” Dan Bailey, FVL program director, told me after a CSIS panel today. The bulk of the work will happen in 2018, he said, with technology demonstrations “maybe into 19.”

Dan Bailey

At least at first, the optionally-piloted feature will not be used on the Joint Multi-Role demonstration aircraft, which are testing out technologies for FVL, said Bailey. (Bailey runs both programs). (This approach is obviously spreading through the Pentagon. The B-21 bomber is also meant to be optionally manned, though that may not happen for some time.) For JMR, which seeks speeds conventional helicopters simply can’t manage, Bell is building its V-280 Valor tilt-rotor and a Boeing-Sikorsky team is building a rotor-and-propeller aircraft called the SB>1 Defiant. Bailey thinks these two novel aircraft will be busy with flight tests, and he doesn’t want to “hinder” the expansion of their flight envelopes by adding a bunch of optional-piloting system tests as well.

There’s “potential” to test optional piloting on the JMR prototypes in the longer term, Bailey told me, but “initially, it’s on something else.”

K-Max in Afghanistan

That “something else” will likely be a current helicopter with an unmanned option added on. Lockheed Martin converted an obscure logging helicopter into a cargo drone, K-MAX, used by Marines in Afghanistan, Bailey noted. Sikorsky converted an old model of its UH-60 Black Hawk, the Army’s workhorse, into an optionally piloted aircraft.

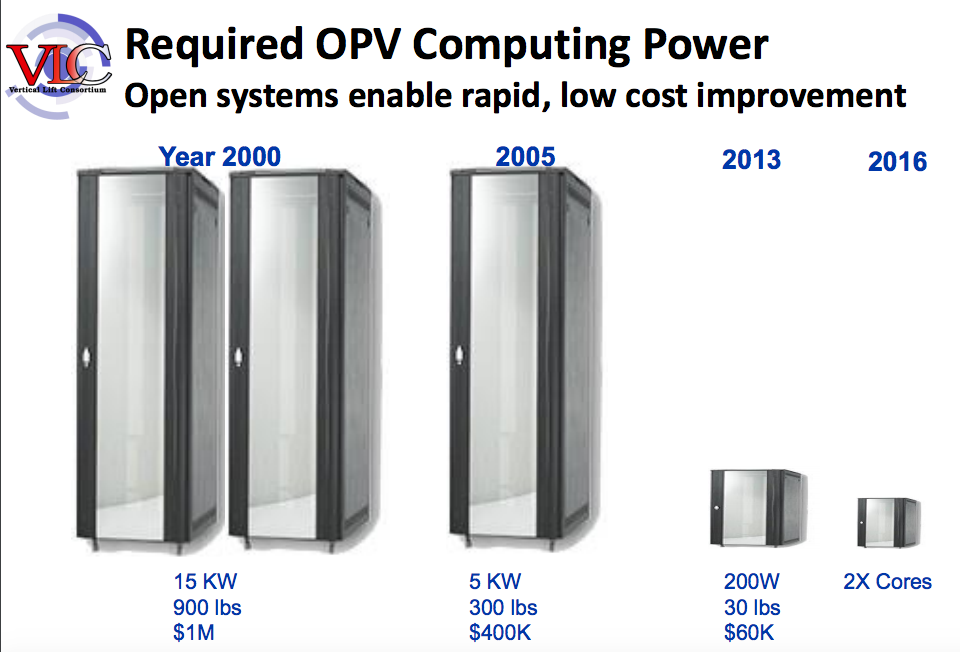

This work is made possible by tremendous progress on information technology, said Sikorsky Innovations VP Chris Van Buiten, speaking at the CSIS panel. (Sikorsky is now part of Lockheed Martin). Back in 2000, he said, to get enough computing power to fly a UH-60 unmanned, you’d have to fill the helicopter’s cabin with racks of hardware, he said, about 900 pounds of it, producing so much heat you’d have to keep the side doors open for cooling. By 2013, you could do the same job with 30 pounds of computer, and it just keeps getting smaller. Because of these trends, he said, “Future Vertical Lift will likely be an optionally piloted aircraft… moving cargo missions with no one on board.”

Computing hardware required to fly a helicopter unmanned (courtesy Chris Van Buiten/Lockheed Martin)

There’s lots of other work to build on. “The Marine Corps’ been doing the K-MAX unmanned cargo piece, which really was an extension of an Army effort (in which) we had small remote control helicopters out in California,” Bailey told me. “We have a whole suite of algorithms that allow that aircraft to operate autonomously. We’ve now moved those into our fly by wire Black Hawk out in California and we’ve done actually complete approaches to a landing zone, take off from the landing zone, autonomously — with safety pilots onboard.”

Bell V-280 Valor Joint Multi-Role Demonstrator

“I want to now take all of that work and put it together from an operational perspective,” Bailey went on, “because the piece we don’t yet know is things like what missions, what CONOPs (Concepts of Operations), would we potentially go after in terms of using optionally piloted or unmanned systems.” As one hypothetical example, he said, aircrew could man their helicopters for an intense combat mission, then take their mandated crew rest and prep for the next air assault while the helicopters fly themselves off to get supplies.

Cargo missions are the natural starting point for unmanned helicopters, flying predictable routes with no lives at stake, friendly or enemy. But when human passengers are aboard, you’ll need at least a “safety pilot” overseeing the autonomous systems, Bailey said. For high-stakes combat situations requiring tactical decision-making by a human brain, you’d want a pilot and a co-pilot as “backup.” Since the military uses the same aircraft for all three kinds of missions — routine supply runs, personnel transport, and air assault — you want to be able to have zero, one, or two pilots as appropriate.

Hence the appeal of making an aircraft optionally piloted, rather than permanently unmanned with no option to add a human pilot. But if you assume that two pilots is the default and zero is the exception, said Bailey, you design “a completely different cockpit” than if you assume no pilots is the norm and two pilots is unusual. That’s the kind of complex question the study will take on, he said.

The Sikorsky-Boeing SB-1 Defiant concept for the Joint Multi-Role demonstrator, a predecessor to the Future Vertical Lift aircraft.

Even what it means to be a “pilot” is going to change, Bailey said, from a hands-on operator to a “mission commander” overseeing highly automated systems. Fixed-wing airplanes like airliners and fighters are already evolving in this direction: “They’re mostly hands off the controls, but the pilots are there for real-time mission change, tactical dynamic decision making, those kinds of things,” Bailey said.

“That’s a cultural change,” Bailey told me bluntly. “(It) requires the operational understanding, the comfort, if you will, of accepting the risk that you’re going to do, say, a cargo mission with an aircraft that doesn’t have a pilot in it…. I don’t think that the community at large has embraced that.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.