Navy Rolls Out CYBERSAFE: ‘Our Operational Network Is Under Fire’

Posted on

A high-level cybersecurity task force will present its plan to the Chief of Naval Operations sometime tomorrow. Called CYBERSAFE (one word, all caps), the initiative is intended to overhaul information technology in the comprehensive way the SUBSAFE instruction overhauled all submarine safety after the USS Thresher disaster. Fixing up IT procurement, though, is just one step towards a larger cultural revolution: treating military networks not as tech support but as weapons.

Adm. Michael Rogers

We are now paying the price of “decisions made over the last 10 or 20 years in which the network was taken for granted,” said Adm. Michael Rogers, the Navy four-star who heads US Cyber Command and the National Security Agency.

“We really never put a lot of thought into the idea that it might actually be contested, that an opponent might actually want to take away our C2 [command-and-control] links, or that redundancy, resiliency, and defensibility were really core design characteristics,” Rogers said at last week’s Sea-Air-Space conference. “It was all about maximum output at the best price.”

Today, by contrast, the military must “operate the network as a warfighting platform,” said Vice Adm. Jan Tighe, head of Navy Cyber Command, “[even though] it wasn’t procured in the way that we’d procure a warfighting platform…. It’s not a service provider, it’s not a support capability. We know that our operational network is under fire every day; we have to defend it.”

Vice Adm. Ted Branch

The final wake-up call was Iran’s September 2013 hacking of the unclassified Navy-Marine Corps Intranet. By the following August, the Navy’s cybersecurity efforts had coalesced into what was grandly dubbed Task Force Cyber Awakening. After initially focusing on network defense, the task force broadened its perspective to look at the vulnerabilities of the Navy’s weapons systems themselves. That’s why the task force draws on all three of the Navy’s procurement commands: Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR), Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA), and Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR). At the helm is Greenert’s chief aide for “Information Dominance” (staff section N2/N6), former fighter pilot Vice Adm. Ted Branch.

“We’re ready now to roll out what we call the CYBERSAFE instruction,” Branch told the conference. “A hundred-day plan for that rollout is ready to launch as soon we have a CNO okay,” he said, which may come as early as the 21st.

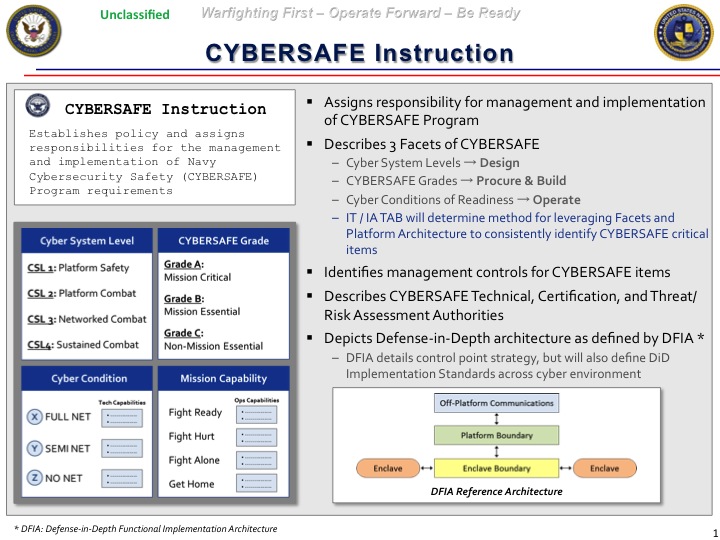

CYBERSAFE is a triaged approach, not an attempt to fix everything at once. It will create a “graduated” set of security requirements, with the strictest standards for a “subset of critical components,” Branch said.

Briefing slides from Branch’s staff describe four critical areas:

- “Platform [i.e. ship or aircraft] Safety: Systems critical to safe maneuver and control of platform

- “Platform Combat: Systems critical to self-defense, C2, and employing organic sensors and weapons

- “Networked Combat: Systems critical to employing networked sensors and weapons

- “Sustained Combat: Systems critical to logistics and maintenance support of above 3 cyber system levels”

Those systems fall (unevenly) into three levels of protection. “[At] cybersecurity level one, some of the most critical components may indeed need to have a very high pedigree, a trusted boundary, and a supply chain tracking scheme [for] the integrity of those component parts,” Branch said. “Cybersecurity level two may be something like CANES [a Navy shipboard network] now, where we have a very well-defined set of standards and products and we let vendor-partners compete to try to hold down the cost.”

“Then cybersecurity level three might be something like business systems,” he said, “where we do lowest-price technically acceptable kinds of contracts.” LPTA competitions are notoriously unpopular with most contractors, who see them as rewarding lowball bids. But the briefing slides make clear the minimum “technically acceptable” standard would be equal to commercial sector “best practice.”

Cybersecurity standards must be applied and re-applied to every system throughout its service life, not just at initial acquisition, Vice Adm. Tighe emphasized. “Once it delivers, even if it delivers perfectly — zero vulnerabilities, zero attack surface — the next day, it will be vulnerable because of a new discovery, a new zero day [exploit],” she said.

Vice Adm. Jan Tighe

Speed is paramount, Tighe said: “We’ve got to be able to respond to requirements coming from our national command authority” — that is, the President and the Secretary of Defense — “that were not anticipated a week before.”

“Traditional acquisition can’t keep up with the pace of cyberspace operations,” agreed Col. Gregory Breazile, a Marine Corps cyber expert on the panel. “The whole DoD struggles with this. We all recognize that cyber is a different domain and moves at a rapid pace, and tomorrow our threat will evolve, much like our IED (Improvised Explosive Device) threat when we had Marines getting killed, and we had to adapt and re-adapt to new threats every day….We stood up an organization (JIEEDO) to go after that and we gave them the ability to rapidly procure things.”

Comparing computer viruses to roadside bombs is perhaps hyperbole — today. In a future conflict, against an adversary that can crash our networks, mislead our weapons, or jam our communications, protecting the network might quite literally be a matter of life and death.

“If you’re just talking cyber, it’s wrong, it’s got to be part of this larger context,” said Maj. Gen. Daniel O’Donohue, head of Marine Corps Forces Cyberspace. A sophisticated enemy won’t just conduct cyber attacks in isolation, he said, but as part of a multi-front offensive in both cyberspace and physical space: “Things that happen on the network might be the first things that might cue to larger actions.” That means, he said, that the people who operate the military’s networks must “fundamentally” remake themselves as warfighters.

Conversely, said Breazile, every other military specialty needs training on cyberspace. “Especially in the Marine Corps, we love to blow things up, but we really want to understand and have our operational folks understand that cyberspace is another capability that they should be planning for,” he said. “They don’t even understand the vulnerabilities we have.”

The revolution that’s required goes far beyond technical standards, Adm. Rogers said. “We have got to get beyond focusing on just the tech piece here. It’s about ethos. It’s about culture. It’s about warfighting,” he said. “It starts to drive how you man, train, and equip your organization, how you structure it, the operational concepts that you employ.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.