Navy Cagey, Boeing Cocky, Over F-18’s Future

Posted on

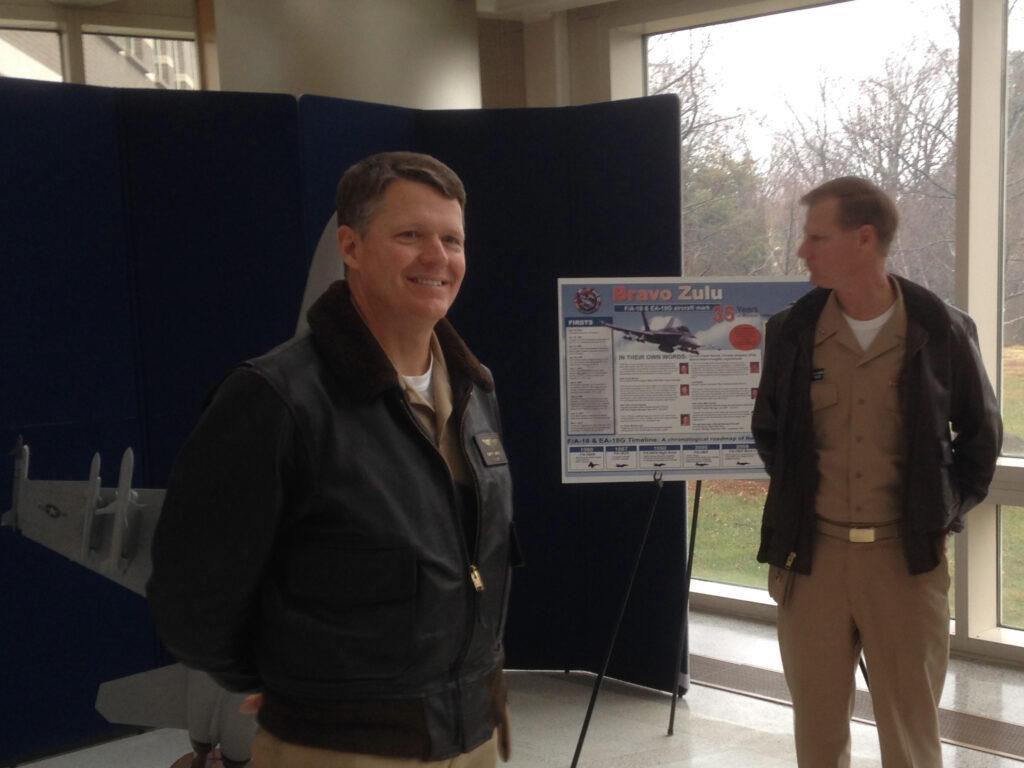

Navy Captain Francis Morley (left), program manager for the F-18 family of jets, and his boss Rear Adm. Donald Gaddis (right) at today’s ceremony celebrating the 35th anniversary of the first Hornet.

PATUXENT RIVER NAVAL AIR STATION: “My job is to preserve options and that’s what I do,” said Capt. Francis Morley, Navy program manager for the F-18 fighter family. Will the Navy press ahead to buy more F-18s in the face of what seems pretty determined opposition from the Office of Secretary of Defense, eager to preserve F-35 funding? “I’ll let the folks in the building figure out what numbers they want,” Morley said.

In October, the Navy issued and then withdrew a pre-solicitation for “up to 36” F/A-18E/Fs and EA-18 Growlers to be bought in fiscal year 2015, when current long-term plans call for zero. “That was an error — my responsibility,” Morley said. “It got everybody excited, [but] it was no indication of what the intent was for FY ’15. That was purely the program maintaining options.”

In fact, Morley said, withdrawing the pre-solicitation was a formality that didn’t actually take any options off the table: “The decision space is still here.”

What about rumors that the Navy withdrew the F-18 pre-solicitation because the Office of the Secretary of Defense came down like a ton of bricks on a potential threat to its favorite plane, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter?

“Didn’t happen,” said Morley. [But do we believe him? — the editor]

“We spend too much time on this F-18 vs. JSF [question],” added Morley’s boss, Rear Adm. Donald Gaddis, who oversees all Navy fighter programs. No matter what happens with the Hornets, the Navy F-35C won’t enter service until 2019 and will take years to enter the fleet in numbers. “Until JSF does arrive in the fleet,” Gaddis said, “the Super Hornet is Navy aviation. That’ s our striking power, it’s the mainstay of our force structure, and there’s nothing else out there.”

“Y’all talk a lot about leadership’s commitment to the JSF, but leadership is just as committed to the Super Hornet and to the Growler,” Gaddis said, and it’s going to invest in upgrading and sustaining both aircraft for two more decades. Ah, but whose leadership, we wonder?

Even Gaddis’s ringing endorsement of the F-18, however, doesn’t actually answer the question of whether the Navy hopes to buy more in 2015, let alone whether OSD will allow it.

Boeing is “Bullish”

While the Navy was cagey, Boeing seemed almost cocky.

“I can easily envision a production line going beyond 2020,” said Mike Gibbons, who runs the Super Hornet and Growler programs at Boeing. Despite the current official plan to end purchases of the jet in 2014, “there could be several more years of buys by the US Navy.”

In fact, he told reporters in a Hornet hanger here at Pax River, he’d bet money on it. And betting its own money, tens of millions of dollars of it, is exactly what Boeing may have to do to keep production going on certain long-lead-time items if it doesn’t get a definitive answer before March 2014.

Even if the Pentagon keeps F-18s out of the ’15 request, the plane’s supporters on Capitol Hill — most notably Rep. Randy Forbes — might manage to vote them back into the budget. But “I’m not looking for Congress to add jets,” Gibbons said: He is “bullish” that the Pentagon will ask for more.

Outside the US, Boeing is pursuing at least nine potential foreign customers, although not all of them all of them have committed to buying any new aircraft, let alone show a particular preference for the F-18 family: “Brazil, Malaysia, Canada, Denmark, Kuwait” – which already has older-model Hornets — “[and] several countries in the Mideast that we don’t discuss by name,” Gibbons said, and he has hopes the Australians will buy more planes on top of their recent purchase. Win even a few of those sales, he said, and “at 24 [planes] per year that gets you beyond 2020 easily.” (Australian officials have said publicly they do not plan to buy more F-18s.)

The line currently builds 48 jets per year and is headed down to 36 (which was, not coincidentally, the maximum number in the withdrawn solicitation). It can go as low as 24 before it becomes uneconomic. As you lose economies of scale in ordering supplies, said Gibbons, “our practical minimum is two jets per month.”

At that rate, and buying a year’s worth of aircraft at a time instead of signing a bulk-buy “multi-year procurement” contract, the price of the jet Boeing delivers (which doesn’t include the engine) will rise from the current $37 million to somewhere closer to $40 million. (A complete Super Hornet, with engine and electronic warfare gear, currently costs about $51 million, he said, while a fully equipped Growler costs about $60 million).

Currently, “there is no plan to shut down the production line,” Gibbons said, which would require the Navy to sign a shut-down contract costing “hundreds of millions of dollars.” And, he went on, “I actually believe, based on the amount of interest at the top [in the military], that we won’t be embarking on that production shutdown next year.”

In fact, between the hoped-for future F-18s and the F-15s Boeing is building for the Air Force, Gibbons predicted that the company’s Saint Louis aircraft factory will be able to keep making those aircraft until the next generation comes along: the Air Force’s long range bomber, its future air-superiority fighter the F-X, its proposed T-X trainer, and then the Navy’s UCLASS drone and future F/A-XX strike fighter. “We’re putting a lot of investment in all of those,” he said. “We will never have a production gap in Saint Louis.”

What Gibbons didn’t mention was that most of those aircraft are more aspirations than actual programs – the F-X and F/A-XX are especially hypothetical – and it’s far from guaranteed they’ll happen, let alone that Boeing will win them. In fact, in the current budgetary chaos on Capitol Hill, it’s hard to predict how much money the Pentagon will have next year, let alone what it will spend it on.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.