NATO, Russia Prep Biggest War Games Since Cold War

Posted on

WASHINGTON: Within the next several weeks, both Russia and NATO will kick off some of the largest military exercises since the end of the Cold War. Hundreds of thousands of troops, tens of thousands of vehicles, hundreds of aircraft, and dozens of warships will charge into action in a series of mock engagements stretching from China to Iceland, from the North Atlantic to the Mediterranean.

WASHINGTON: Within the next several weeks, both Russia and NATO will kick off some of the largest military exercises since the end of the Cold War. Hundreds of thousands of troops, tens of thousands of vehicles, hundreds of aircraft, and dozens of warships will charge into action in a series of mock engagements stretching from China to Iceland, from the North Atlantic to the Mediterranean.

Russian officials are openly advertising their Vostok war game as the country’s largest since 1981, with plans to put a staggering 300,000 troops in the field along with 900 tanks. Moscow has also has secured the participation of over 3,000 Chinese troops who will link up with Russia near the Chinese and Mongolian borders. Meanwhile, Russian naval forces have unexpectedly announced an exercise in the Mediterranean, warning other nations to stay away and arousing suspicions the drills are cover for intervening in Syria.

Russia’s massed maneuvers and increasing closeness to China, the West’s most powerful challenger, has raised eyebrows in Washington and among capitols throughout Europe and Asia — but Moscow has its own concerns. Russian officials are nervously eyeing the start of what promises to be NATO’s largest war game since the end of the Cold War. Trident Juncture 2018 is slated to take place in Norway in October and November, with the added twist of thousands of non-NATO troops from Finland and Sweden participating, along with air bases and ground training areas in those two countries.

The Trident Juncture series of exercises has grown into the alliance’s most ambitious undertaking in decades, featuring 40,000 troops from all 29 NATO members, 70 ships, 150 aircraft, and 10,000 ground vehicles, all under the command of the U.S. Navy’s Adm. James Foggo, head of the Joint Forces Command Naples.

Perhaps most significantly, the exercise will also serve as the final certification of NATO’s new Spearhead Force — also known as the Very High Readiness Joint Task Force — to be led by Germany’s 9th Armored Demonstration brigade. The force is designed to be capable of deploying within 48 hours of being called up. The 8,000-strong unit also includes infantry from the Netherlands and Norway.

Such a massive and coordinated show of force is hugely important for NATO, and comes during a time of uncertainty over the Trump administration’s commitment to international organizations and agreements.

President Trump has upset the traditional leadership role occupied by Washington by attempting to pull out of trade and climate agreements in Asia, North America, and Europe, and just this week reaffirmed that he sees no reason to restart critical military exercises in South Korea that keep U.S. and South Korean forces sharp in case of a conflict with North Korea.

Trump’s Twitter message Wednesday that “there is no reason at this time to be spending large amounts of money on joint U.S.-South Korea war games” came as a surprise to the Pentagon. DoD released an assessment in July that the largest of the suspended exercises, Freedom Guardian, cost $14 million. For comparison, a single F-35 costs over $90 million, and the Pentagon is set to buy 89 of the aircraft in 2019.

The White House has remained silent about Trident Juncture, despite president Trump’s July meeting with Russian president Vladimir Putin and his efforts to revive the relationship between Washington and Moscow. Questions submitted to the Pentagon and NATO over the cost of Trident Juncture, and price tag of the U.S. role, went unanswered by time of publication.

The NATO effort will begin in mid-October in Iceland, in what one person familiar with the planning told me would be an amphibious landing by U.S. Marines. The Marine Corps and the government of Iceland confirmed that there will be Trident Juncture-related activities in Iceland in mid-October, but would not confirm what they are.

Allies Stepping Up

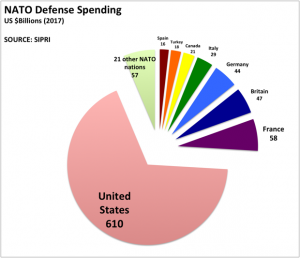

One criticism that president Trump has thrown at NATO allies since his presidential campaign is that European countries don’t pay enough for their own defense, and expect the United States to carry much of the weight. His disruption of the annual NATO summit in Brussels in July was the latest in his long-running public complaints over the health of the organization, and his conviction that the balance sheet of “unfair” toward the United States.

Just two days after the summit, Norway sent two F-35s to escort Defense Secretary James Mattis into Oslo, a sure sign that the country was keen to advertise it’s spending on American military equipment, even though the country has yet to meet the agreed-to goal of spending two percent of GDP on defense.

But the new exercise will show that other countries who have yet to meet the goal are capable of playing a big role in the alliance. Germany — despite shocking issues with readiness that have grounded aircraft and kept submarines in port — will contribute 4,000 troops to Trident Juncture, third only to the 12,000 American and 6,500 Norwegian forces.

The U.K. will send 3,500 troops, France 3,000, Canada 2,000, Denmark 1,000, Italy 1,500, Spain 1,000, and the Netherlands 1,500.

Russian Concerns

As Russia monitors the exercises, it will be particularly vexed by two non-NATO countries taking part: Finland and Sweden. Finland, a country which has traditionally tried to balances ties to both NATO and Russia, is contributing about 2,000 troops. It will also provide ships and aircraft, and will allow NATO aircraft operate out of its Rovaniemi air base. The participation represents a massive increase for Finland: During the last Trident Juncture in 2015, about 160 Finnish troops participated.

Sweden, which has increasingly flirted with the idea of joining NATO, is also taking Trident Juncture seriously. About 2,200 Swedish troops will participate, along with four Gripen fighters to be based in Norway during the drills. Just before the main event kicks off, Swedish, American and Finnish forces will conduct their own exercises in Sweden, and “transports of other foreign units through Sweden will occur” during the event, a Swedish official told me via email.

Sweden’s goal in participating is meant to “increase our national capability and also strengthen our cooperation with Finland, the United States and NATO,” the official said. “The exercise will also prepare our naval and air power units for their upcoming participation in the [NATO Response Force], and our ground forces will exercise with the aim of strengthening their brigade capability. ”

The exercise will present a scenario in which the alliance has agreed to an Article 5 declaration, in which Norway has been invaded by a foreign force and the rest of the alliance springs into action. As a result, convoys with thousands of troops will race almost 400 miles north from Oslo to the area around Trondheim near the Arctic Circle, while ships at sea hunt for submarines and fight off enemy ships and aircraft.

The plan is to test on-the-fly logistics in an environment where electronic jamming is prevalent and full control over the skies isn’t a given.

Adm. Foggo, speaking in Norway in June, said that the “sheer size of the exercise gives Norway as host nation an excellent opportunity to realistically train reception and support of substantial Allied reinforcements. And NATO gets to test their plans for the reinforcement of Norway.”

Norway received a taste of what it might face in the opening salvos of a war with Russia in March 2017, when waves of Russian bombers and other aircraft made approaches toward the Norwegian radar station at Vardo, near the Russian border. Norway scrambled F-16s to intercept the aircraft after they pushed toward the secretive costal installation which houses U.S.-made radar systems that help keep watch on Russian submarine and naval activity. Two months later, Russian bombers made similar feints toward other Norwegian bases in the far north.

The participation of the Nordic countries in such a deep way likely makes Moscow uneasy.

“Norway, Finland and Sweden represent an unknown for the Russians,” said Jim Townsend, a former Pentagon official who was intimately involved in NATO issues. “If you’re a Russian planner, you don’t know what the Norwegians might do,” Townsend told me. “They used to be neutral, but now they’re seasoned, and you’re going to have to deal with them.”

Finland and Sweden have increasingly inched toward the NATO orbit as Putin’s Russia has grown more unpredictable, taking down Estonia’s internet, invading Georgia, annexing Crimea, and waging an ongoing proxy war in eastern Ukraine over the past 11 years. Both countries have sent troops to Afghanistan, and have become more deeply involved in NATO exercises.

“Every day that goes by those countries get stronger,” said Townsend, now at the Center for a New American Security. “So they present a complication for the Russians.”

Sweden in particular has “shied away from doing Article 5 exercises before,” Townsend continued, citing the article of the NATO treaty that requires member states — which Sweden, of course, is not — to come to each others’ defense if attacked. “In Stockholm,” he said, “they have felt like if they take part in an Article 5 exercise that shows they’ve gotten too close” to NATO.

Norway, the ‘Sentinel of the North’

During Mattis’ visit to Oslo in July, Norway’s chief of defense, Adm. Haakon Bruun-Hanssen, reminded reporters, including Breaking Defense, that Russia’s formidable Northern Fleet is based only about 60 miles from his country’s border. That puts Norwegian ships in regular contact with Russian vessels in the Barents Sea and North Atlantic.

The main Russian naval testing ground sits in international waters off Norway’s coast, something Bruun-Hanssen claimed was of little concern to his government, but which might make the Trident Juncture naval exercises a bit more interesting.

“We don’t believe it directly threatens us,” he added “but it does threaten NATO,” making it an issue Oslo takes seriously.

“Russia is a competitor to the United States and the western order, and they are attempting to use military force as a means to change the world order in favor of what the Russians want,” the admiral said. But “we acknowledge and accept that this is the Russian training ground.”

“Russia is a competitor to the United States and the western order, and they are attempting to use military force as a means to change the world order in favor of what the Russians want,” the admiral said. But “we acknowledge and accept that this is the Russian training ground.”

In addition to the flights near Norway’s military bases, Russia has also attempted to jam Norwegian military communications, Bruun-Hanssen said. “I wouldn’t say that it is sophisticated jamming, but we have experienced on a number of occasions that they have jammed our GPS,” He said it’s “hazardous” for pilots operating close to Russian and civilian aircraft.

All of this close-in activity makes Norway the “Sentinel of the north,” as Mattis said during his visit.

While Russia and NATO will watch one another’s exercises this fall very closely, it’s clear that the sheer size of the war games are intended, at least in part, to garner just that attention.

NATO spokesperson Dylan White told me that Russia has briefed the alliance on the Vostok exercise, and it “demonstrates Russia’s focus on exercising large-scale conflict.” It also “fits into a pattern we have seen over some time: a more assertive Russia, significantly increasing its defense budget and its military presence. Over the past years, we have seen a significant military buildup by Russia, including in the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea regions, and in the Mediterranean.”

Moscow, of course, points to the new NATO deployments to the Baltics, the growing American relationships in the Balkans, and things like Sweden’s recent agreement to purchase the Patriot missile defense system as ways in which NATO is militarizing its Russian frontier.

Whatever merits either argument has, once thing is clear. The race is on, and this fall, the hardware will be rolling across northern Europe and Asia in a series of public signals that neither side is interested in losing.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.