NATO Ops Center Goes 24/7 To Counter Russians: Gen. Scaparrotti

Posted on

M2 Bradleys of 3rd Armored BCT, 4th Infantry Division on a rail car in Poland.

NATO is dusting off Cold War concepts such as deterrence, rapid reinforcement and battle readiness as it faces a Russian destabilization campaign. Our contributor James Kitfield is traveling with Gen. James Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, as the Marine general attends the NATO summit in Warsaw. Kitfield spoke with Gen. Curtis Scaparrotti, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander, about the Russian threat in the former Soviet and Russian vassal state. One of James’ cab drivers described Warsaw as a speed bump between Berlin and Moscow, just to put everything in perspective. Scaparrotti wasn’t quite as vivid, but he made clear in unequivocal terms that Russia is America’s top threat. — the editors

WARSAW – Only 80 years ago Nazi Germany and the Soviet Red Army dismembered Poland in tandem at the outset of World War II. After the Nazis brutally crushed the 1943 Jewish uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto, and a more general Warsaw uprising by the Polish resistance in 1944, Hitler ordered the city razed as a lesson for others who dared oppose the Third Reich. Soon after, advancing Red Army “liberators” made clear who would run Poland, arresting the leaders of the Polish resistance and sending them to Soviet gulags, paving the way for decades of occupation.

“As Chief of the General Staff, and as a Polish officer and citizen, I believe Poland’s historical context is important,” said Lt. General Rajmund Andrzejczak, welcoming the heads of NATO’s Military Committee to Warsaw this weekend. “We Poles understand what independence is about because we lost our independence for 123 years of our history. Without a common understanding and without the NATO alliance building an environment of security, our independence is not possible.”

The flat ground of the European Plain has provided a natural pathway for invaders since prehistoric times (Wikimedia Commons)

With threats and menace once again rumbling in the East, it was fitting that NATO held its annual Military Committee Conference this past weekend in Warsaw. Russia’s forced annexation of Crimea and military intrusion into eastern Ukraine beginning in 2014, following the Russian Army’s 2008 occupation of “breakaway” provinces in Georgia, have finally awaken the Western military alliance from its long, post-Cold War slumber.

Just weeks ago Russia launched Vostok-2018, its largest ever military exercise, and a showcase for its military modernization that Moscow has sustained despite economic sanctions. The military drills included some 300,000 Russian soldiers, 36,000 military vehicles, 80 ships and 1,000 aircraft, helicopters and drones. A contingent of Chinese troops even took part.

According to Bob Woodward’s new book Fear” Russian officials have privately warned the Pentagon that in the event of war involving NATO allies in the Baltics, Moscow would not hesitate to use tactical nuclear weapons. Of course, Russians have threatened NATO with nuclear strikes several times since the collapse of the former Yugoslavia. Most recently, Russian President Vladimir Putin has also unveiled a new arsenal of hypersonic weapons billed as “invincible” and “unstoppable” (even if they aren’t deployed yet).

Meanwhile, Russia continues to execute a hybrid destabilization campaign aimed at Western democracies, which includes persistent cyberattacks, sophisticated disinformation operations, interference in U.S. and European elections, and targeted assassinations. Last week the investigative journalism organization Bellingcat revealed that one of the so-called Russian “tourists” suspected by London of attempting to kill a former Russian spy on British soil with nerve agent was actually a decorated colonel in Spetsnaz, a Special Forces unit under command of Russia’s military intelligence agency, the GRU.

Gen. Curtis Scaparrotti (at right, in blue) chats with Estonian Gen. Riho Terras in Tallinn, Estonian

Scaparrotti On Russia

So when I asked Gen. Curtis Scaparrotti, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander, whether Russia is the Western alliance’s number one national security threat, he was unequivocal.

“Yes, absolutely,” he said on the sidelines of this weekend’s NATO Conference in Warsaw. Russia is operating in domains below the level of outright war, he said, in a very aggressive way. “If you look at their cyber and social media activity, their disinformation operations, and their money and support to European organizations and political groups on both ends of the political spectrum, they are doing those things in many European countries. In my view they are executing a destabilization campaign, based on a strategy that assumes if they can destabilize Western governments it will be to Russia’s benefit. If you look at their military doctrine, that is part of what they call ‘indirect activity.’ They believe undermining Western governments without ever firing a shot achieves their ends.”

Royal Air Force Eurofighter Typhoons take off from Amari Air Base in Estonia during a Baltic Air Patrol mission.

While Russia is executing that hybrid destabilization campaign in many Western countries, including the United States, Scaparrotti notes that NATO’s eastern allies bordering Russia remain the focus of Moscow’s most malign activities and threats, to include Poland and the Baltic states of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia.

“The Russians have always seen those countries along the eastern border of the NATO alliance as a region of privileged influence for them, and they want to continue to be able to exert influence there,” he said.

That campaign of intimidation began in earnest back in 2007, when the Estonian government decided to move the bronze statue of a Soviet soldier – originally called the “Monument of the Liberators of Tallinn” – from the center of the capital to a military cemetery on the outskirts of the city. After decades of occupations, the Estonians simply didn’t consider the Red Army as liberators. Predictably furious, Moscow launched a disinformation campaign and cyberattacks that provoked deadly riots and effectively shut down the country’s banking and government services for weeks.

Since then Russia has aggressively pushed back at what Moscow sees as the West’s encroachment into its privileged “sphere of influence,” including the military occupation of “breakaway” provinces in Georgia in 2008 and culminating in the forced annexation of Crimea and the military incursion into Ukraine in 2014.

“Ukraine in 2014 was the real wake up call, because that violated many international laws and norms, which Russia continues to do in a number of different ways,” said Scaparrotti. “I have no doubt that if the Russians see the opportunity in the future, they will do something similar, if they judge that the benefits are greater than the costs.”

That realization has prompted a dramatic change in NATO’s posture and mindset. Scaparrotti’s staff at SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe) in Mons, Belgium, have spent considerable time and effort dusting off old Cold War concepts such as deterrence, rapid reinforcement and battle readiness.

“I can’t tell you how many times in last two years I’ve asked our historians to go back and analyze battle plans and readiness documents from the viewpoint of past SACEURs, beginning in the 1950s at the outset of the Cold War, to inform me how they thought about readiness and speed of action, and to see how that relates to our challenges today,” said Scaparrotti, whose own organization is already reflecting some of those lessons.

“Previously my headquarters didn’t have an Operations Center that was manned 24/7, but we do now. It’s like the old saying: ‘history may not repeat itself, but it rhymes,’” he said. “Those of us who were on the frontlines in Europe [during the Cold War] remember some of the standard operating procedures of those days, but there aren’t too many of us left below my rank.”

Countering Hybrid Warfare

The most tangible sign of NATO’s new mindset was the European Deterrence Initiative, which was established after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea to reassure nervous allies that share a border with Russia.

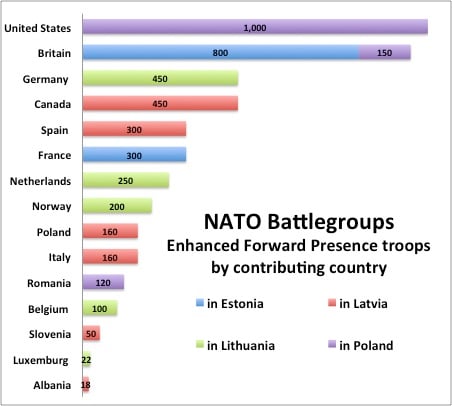

That led to the deployment of four multinational Battle Groups to the Baltics and Poland, each led by a “framework nation.” Canada leads the battle group deployed to Latvia, Germany leads in Lithuania, and Great Britain in Estonia. The U.S.-led Battle Group Poland is anchored by roughly 1,200 soldiers from the 278th Armored Calvary Regiment of the Tennessee Army National Guard, augmented by a British reconnaissance unit and a Romanian air defense battery. The battlegroup exercises jointly with the Polish Army 15th Mechanized Brigade. Through “heel-to-toe” rotations lasting nine months, the battlegroups maintain a constant presence in NATO’s frontline nations.

In September Polish President Andrzej Duda visited the White House and invited President Donald Trump to establish a permanent military base with a U.S. armored division in Poland, even offering to pay roughly $2 billion and name it “Fort Trump.” NATO officials seem lukewarm to the idea, but already the battlegroups in Poland and the Baltics have taught NATO planners that gaps in capability and interoperability have grown during the long years of the post-Cold War era, when Russia was generally considered a benign actor and potential partner.

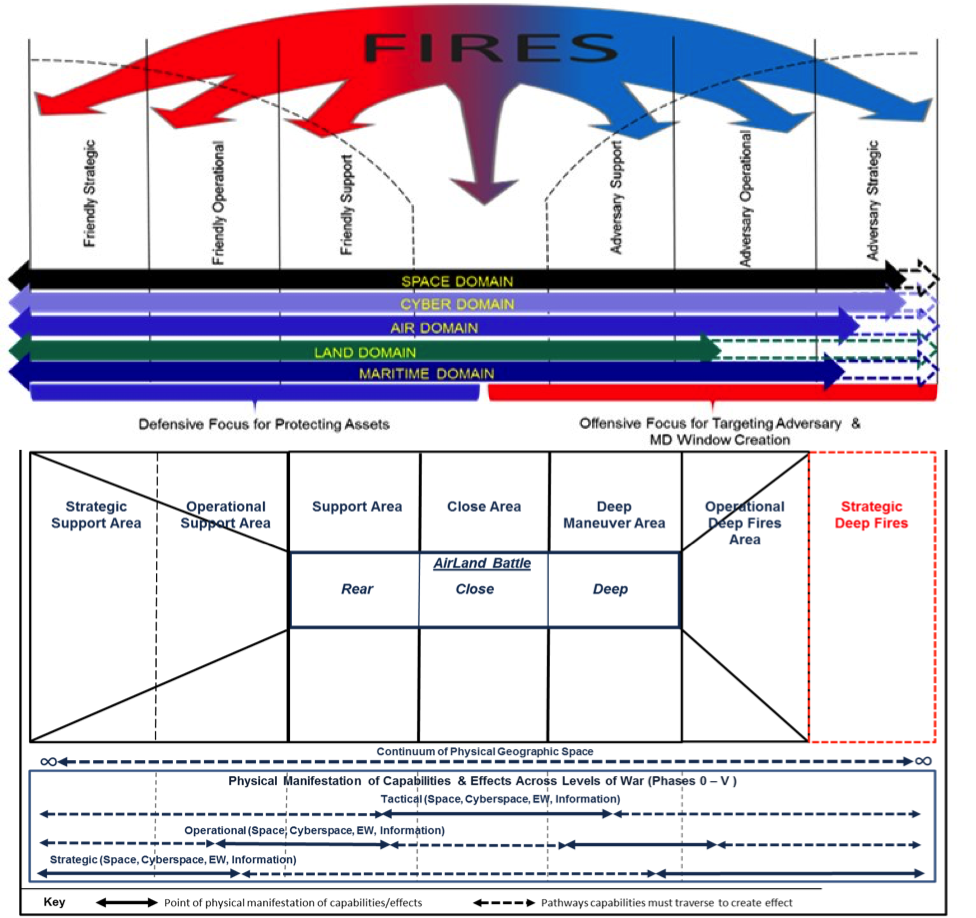

The Polish offer to host a permanent base “is a great opportunity to work with them and strengthen this relationship, but I have to look at it from the holistic viewpoint of the whole alliance,” said Scaparrotti. As to lessons learned from deploying the battlegroups, he notes that they operate in a complex, “multi-domain” environment that includes ground, air, maritime and cyber elements.

“We’ve always known that it’s difficult conducting multinational operations, and we’re learning again how to do that better,” said Scaparrotti. “In that sense I think the battlegroups have been good for the alliance, because they identify shortfalls and capabilities that we need to grow throughout the entire alliance. That’s not unlike Russia learning lessons from its operations in Ukraine that we see them testing and applying in Syria.”

One of the lessons Russia has taken away from Ukraine is the effectiveness of cyberattacks and other forms of electronic warfare. Cyberattacks feature prominently in Russian doctrine for hybrid warfare, which also includes disguised Russian Special Forces, local guerrilla fighters and militias, and information warfare. In NATO circles it’s called the “Gerasimov Maneuver,” for Russian Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov, one of its architects.

“One of the challenges of hybrid warfare is defining exactly what it is because a lot of its activities take place outside the military realm, so we need to determine what we can do with military assets and how we can mount a ‘whole of government’ response that brings in other players,” said Scaparrotti. A new tool in NATO’s toolbox is Hybrid Warfare Teams, heavy on Special Operations Forces, who advise allied nations how to identify and counter hybrid warfare activities, in some cases with the help of military information operations. “What we’ve found is that every nation in the alliance requires a different approach to this threat, because each nation has strengths, weaknesses and vulnerabilities that shape Russia’s activities.”

One vulnerability Russia has clearly identified for potential exploitation remains cyberspace. NATO has responded by establishing the Cooperative Cyber Defense Center of Excellence in Estonia, hiring more cyber experts to harden defenses, and establishing an operations center for more offensive or proactive cyber responses.

“At SHAPE we didn’t wait around for anyone to tell us that cyber is an important domain, or to get authority to put the people with the right skills in place ahead of the issue, because I was being attacked every day,” said Scaparrotti. “We see attempts to breach our command-and-control and communications systems, both classified and unclassified, on a daily basis. And there is no doubt that some of those cyberattacks are conducted by Russian actors. Without going into details, in some cases I personally believe those cyberattacks are connected to the Russian state and the state intelligence apparatus.”

Reinforcement and Battle Readiness

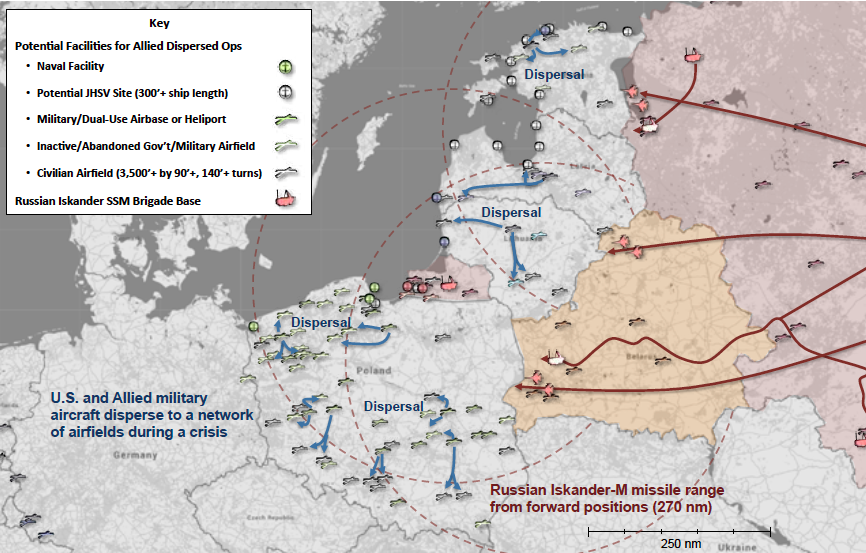

Late last year NATO defense ministers also agreed to create two new commands to facilitate the rapid reinforcement of Europe in the event of a conflict with Russia. An Atlantic Command based in Norfolk will be responsible for securing maritime supply lines to Europe, and Joint Support & Enabling Command in Germany will focus on logistics and speeding the movement of NATO military forces to the east in the event of a Russian incursion. In Warsaw senior NATO military officials also discussed at length how to implement the 30-30-30-30 readiness initiative proposed by Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and endorsed at the NATO Summit in Brussels last July. The “4×30” initiative calls for the alliance to have 30 land battalions, 30 fighter squadrons and 30 ships ready to deploy within 30 days of an alert.

“The NATO mobility project is recognition that we don’t mark bridges for how much tonnage they can support anymore, nor do we think about how many rail cars it will take to move a tank unit, and how wide those rail cars need to be. We stopped putting those kinds of requirements on our logistics systems and infrastructure, and we have to go back to doing that kind of readiness planning,” said Scaparrotti. While the readiness reforms inherent in the 4×30 initiative are welcome, he said, even more important is the mindset reflected in their adoption by the alliance.

“Perhaps the most important thing that has changed is the mindset that we have to get up every day now and be ready to deal with a real threat. That is a fundamental change, and change is the hardest thing for any military organization. Human nature being what it is we’ve taken a bit of time to get to this point,” said Scaparrotti. “So I think the Russians were ahead of us in terms of changing their posture with respect to NATO. It took the West a little longer to recognize that Russia is not our friend or partner right now, and we had better start paying close attention to what the Russians are doing, and how they are acting. But I feel like we have the right focus now.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.