NATO Not Ready As Russian Sub Threat Rises: CSIS

Posted on

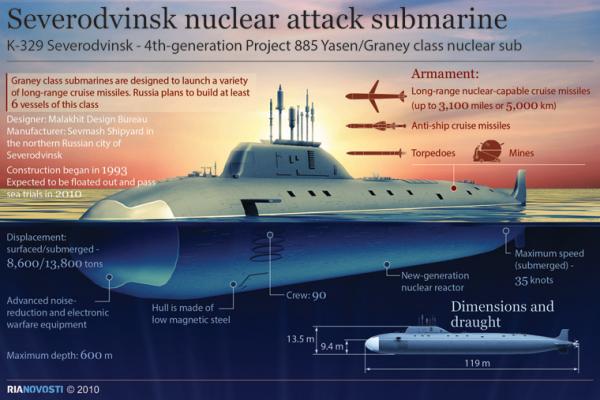

Russia’s most advanced attack submarine, the Severodvinsk class. (Navy graphic)

WASHINGTON: The balance of power underwater is shifting against the West, warns a new report from the Center for Strategic & International Studies. Both Russian and NATO capabilities cratered after the Cold War, but the Russian submarine fleet is clawing its way back — and we’re not ready to face it, CSIS says. The US, its allies, and the Nordics need to invest in new technology, intense training, and, above all, closer cooperation to counter the resurgent threat.

Russian Kilo-class diesel attack submarine

How bad is it? Russia is still a shadow of its Soviet self. Its economy has plunged under sanctions and with the drop in oil and gas prices since 2014, its shipyards remain a rusty mess, and its submarine fleet is one fifth its Cold War size: CSIS counts just 56 operational subs today compared to 240 in 1991. Nevertheless, Moscow has rebuilt a small but capable cadre of professional sailors and modern submarines. A handful, such as the new Severodvinsk attack subs, are reportedly comparable to the US Virginia class in armament, stealth, and sonar.

This restored Russia sub force is also more active than it has been in decades. Patrols remain below Cold War levels, but suspected Russian subs have made politically pointed incursions into Swedish and Finnish waters, and approaches to the British sub base at Faslane, Scotland — incidents to which the Western countries struggled to respond.

“The organizations, relationships, intelligence, and capabilities that once supported a robust ASW (Anti-Submarine Warfare) network in the North Atlantic and Baltic Sea no longer exist,” the CSIS study said bluntly.

“Two things have happened,” naval historian Norman Polmar told me. “One, their submarines are quieter, and, two, we have dismantled a large portion of our ASW capabilities.”

“Bottom line is yes, NATO ASW declined,” said Jerry Hendrix, a retired Navy captain now with Center for a New American Security, who wasn’t involved with the report but agreed with its primary premise. “We’re in a bad place as an alliance with regard to Russia’s underwater resurgence.”

So what does CSIS recommend, besides more spending? The primary points:

- Institutional readiness: Strengthen NATO cooperation with Sweden and Finland, especially through the Nordic Defense Cooperation (NORDEFCO) forum.

- Intellectual readiness: Rewrite the 2011 Alliance Maritime Strategy to reflect the Russian threat and create a ASW “Center of Excellence” that can bring nations’ navies together to create “a common NATO playbook” for anti-submarine warfare.

- Training readiness: Create an international ASW “Command, Weapons, and Tactics” course modeled on Britain’s famously tough “Perisher” school. Increase the number of intensive ASW exercises like the annual BALTOPS (Baltic Operations) wargames and 2015’s beautifully named “Dynamic Mongoose.”

- Technological readiness: Develop an alliance standard for secure, encrypted transmission of ASW sensor data and set up a NATO data fusion center to share and integrate each countries’ sightings of submarines.

Ultimately, says CSIS, the goal is a “federated” approach where each ally contributes in its appropriate niche to a single, coherent picture of the undersea threat and a single, coherent response. So what can the Western allies offer?

British Invasion?

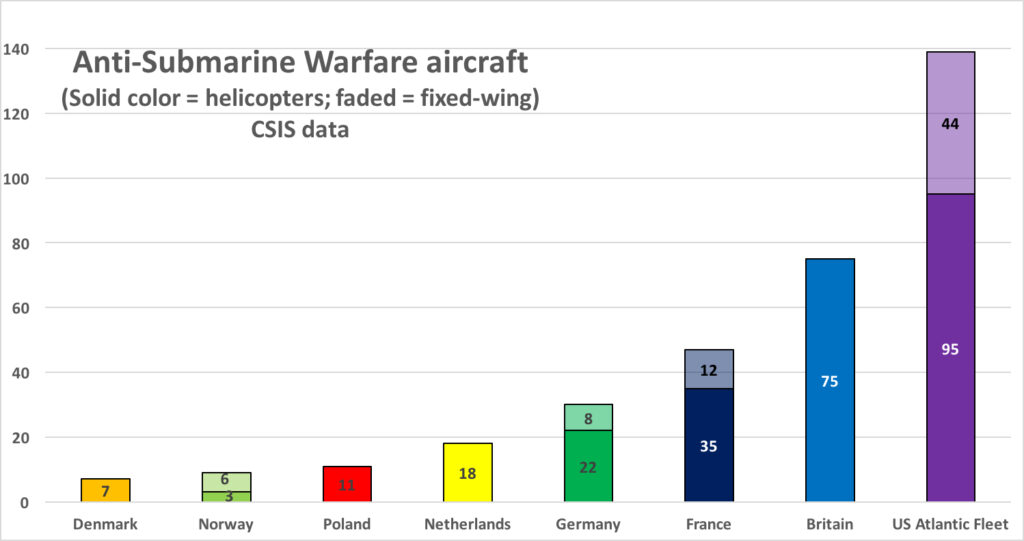

No fleet has fallen harder than the vaunted Royal Navy, which retired its last aircraft carrier, the Illustrious, in 2014 and its Nimrod long-range patrol planes in 2011. “The Royal Navy may be at its lowest ebb” in terms of anti-submarine warfare, the report says, “(but) the coming years should see (it) regain key capabilities.”

“The reason that the UK decided to get out of the maritime patrol aircraft and the carrier based capabilities in 2010 was entirely to do with affordability,” the British Embassy’s Minister of Defense for Materiel, Steve McCarthy, said Friday at CSIS. But even then the UK kept developing the new Elizabeth-class carriers, and ultimately it decided to buy the P-8s. “Five-six years ago we thought it was not such a strategic priority,” McCarthy said, but that’s changed.

Just this month at the Farnborough Air Show, the UK formally signed a contract for nine Boeing P-8 Poseidons, long-range land-based patrol aircraft primarily designed as sub-hunters. Farnborough also showed off the F-35B jump jets that will go on two new Queen Elizabeth-class carriers.

HMS Queen Elizabeth

“The maritime patrol aircraft come into service at the end of the decade; so does the carrier,” McCarthy told me after his CSIS remarks. Britain is also already building the acclaimed Astute-class nuclear submarine, and it’s developing a new Type 26 destroyer, both of which are major advances in anti-submarine warfare.

In the meantime, the UK is getting by with a little help from its friends. The Royal Navy is keeping a small cadre of aircrew in training by sending them on US and Australian P-8s. And in 2014-2015, when a suspected Russian submarine was spotted off Faslane, Scotland — home to the entire British sub fleet and all the UK’s nuclear weapons — the British called in sub-hunting aircraft from its NATO partners.

Asking for help is nothing to be ashamed of, McCarthy told me. To the contrary, he argued, it’s a model of how an increasingly interdependent alliance should work. In fact: “That’s what the alliance is about. We share our capabilities and we support each other. That’s the fundamentals of being in an alliance.”

All Together Now

All Together Now

As anti-submarine warfare becomes increasingly complex, it’s increasingly difficult for any one country — even the United States — to do it alone. One of the CSIS study’s recurring themes is the need to restore and strengthen the close cooperation of the Cold War, technologically upgraded for the information age.

The full Cold War system combined

- stationary sensors, such as SOSUS, to act as an underwater tripwire;

- long-range, land-based patrol planes to respond quickly to possible contacts;

- submarines to stealthily tail any Russian subs detected;

- surface ships with both in-built sonar and helicopters to protect convoys, chokepoints, and key targets.

Both the US and its NATO allies have cut back on all of these.

A 21st century system would also need a robust, secure computer network to rapidly transmit data on sightings. That’s a requirement that runs afoul of sensitivities about sharing highly technical intelligence. The policy and political obstacles are probably more formidable than the technical ones. A modernized ASW system could also make use of drones — in the air, on the surface, under the water — to extend the reach of manned ones or in some cases to substitute for them altogether, for example by having a robotic sub tail a contact instead of a manned one.

Only the US comes close to having all these capabilities — and even then, there are holes. There’s the fraying underwater tripwire that is often the first system to detect a submarine. “The undersea SOSUS arrays that characterized initial search tactics of the Cold War are practically non-existent today,” Hendrix said. Less bluntly, the CSIS report warned the efficacy of the remaining undersea system against modern Russian submarines “is questionable.”

Bryan Clark, formerly a top aide to the Chief of Naval Operations, was more optimistic. “While SOSUS did suffer from lack of attention in the 1990s, it has been reinvigorated and is now part of an Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS) that includes other arrays and the SURTASS surveillance ships,” he told me. “So now you have competing efforts by Russians to quiet submarines and Americans trying to improve the number and capability of passive sensors.”

US Navy P-8 Poseidon

Once you get that initial detection, you need to send something to investigate: a land-based patrol aircraft, a surface ship — preferably with a helicopter aboard — or a submarine. The US has all three, albeit in smaller quantities than in the Cold War. The aging P-3s are being replaced by just 117 P-8s, with the first deployments slated for the Pacific. The Perry-class ASW frigates are all retired and the replacement program, the controversial Littoral Combat Ship, has been cut to 40 vessels. The submarine fleet is shrinking as Los Angeles boats built in the Reagan buildup go out of service faster than new Virginias can be built.

With the US sub fleet shrinking as the Russian one rebuilds, it becomes increasingly difficult to tail each Russian sub detected. The US needs to explore less labor-intensive methods such as drone mini-subs, said Bryan Clark.

“Today, the U.S. can only maintain a few submarines continuously in Europe,” Clark told me. “Since Russia has about 10 newer nuclear submarines in the Northern Fleet, it wouldn’t be hard for them to exceed the capacity of US forces to trail submarines heading to the US coast.” In the worst case, he said, a cruise-missile-equipped attack sub could hold East Coast cities hostage and deter US intervention in a crisis. “The Navy will need to develop and field unmanned systems that can do this track and trail mission instead,” Clark said.

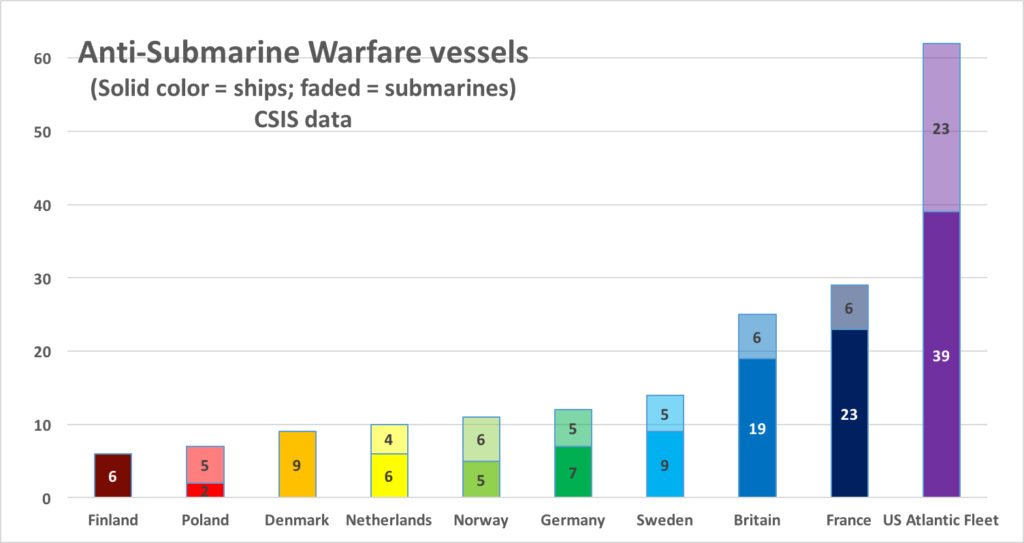

The other, more immediate way to make up the numbers is to rely on European partners and allies. But those nations have cut back even more steeply than the US. Which ones remain most capable can be surprising.

French aircraft Charles de Gaulle en route to Libya during the 2011 air war.

Assessing the Allies

France has one of the most formidable, skilled, and active militaries in Europe. In fact, until the Royal Navy rebuilds, France has the only fleet in Europe with the full panoply of anti-submarine warfare. It has the world’s only nuclear-powered aircraft carrier outside of US service, a recently modernized fleet of patrol aircraft, nuclear submarines, and helicopter-carrying ASW frigates. The one problem, CSIS notes, is that the French are focused on the Mediterranean, with most of their fleet in Toulon, so their ASW may not be available for a North Atlantic conflict.

In the Baltic, the most capable and strategically well-situated ASW fleet is Sweden’s. The Swedes have cutting-edge diesel submarines, the Gotland class. (Saab, which sponsored the CSIS report, just happens to be building Sweden’s next set of submarines). Swedish subs are well-suited to the Baltic shallows, which their larger nuclear-powered American counterparts are not. Nuclear power’s chief advantage is long range — you don’t need to sail home to refuel — but since Sweden is on top of the potential warzone in the Baltic, diesel subs can reach everywhere it needs to worry about.

On the surface, Sweden’s Visby corvettes boast good sonar. The Swedes are still in the process of acquiring ASW helicopters, however, which are essential to extend the reach of surface ships. They have no plans to acquire land-based patrol aircraft, not that such long-range planes are much needed in the narrow Baltic.

Swedish soldier in Afghanistan.

The bigger problem with Sweden is that they’re not actually in NATO. The long-neutral nation has drawn increasingly close to the Western allies in recent years, but it’s not integrated into NATO command structures in the way a major anti-submarine operation would require.

Other nations offer niche contributions. Germany and Norway have good diesel submarines, for instance, while Denmark has disbanded its sub fleet entirely. Norway also has some aging US-built P-3 patrol aircraft and may lease the new P-8s. Poland has an eclectic and aging mix of second-hand Soviet and Western equipment. Finland is tiny but punches above its weight in minesweeping and works closely with the US, despite being outside of NATO.

None of these nations can replicate the full array of anti-submarine warfare by themselves, not even France or the once-and-future Royal Navy. All of them need each other and the United States — and the United States needs them. That’s why CSIS puts such emphasis on collaboration.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.