Minefields At Sea: From The Tsars To Putin

Posted on

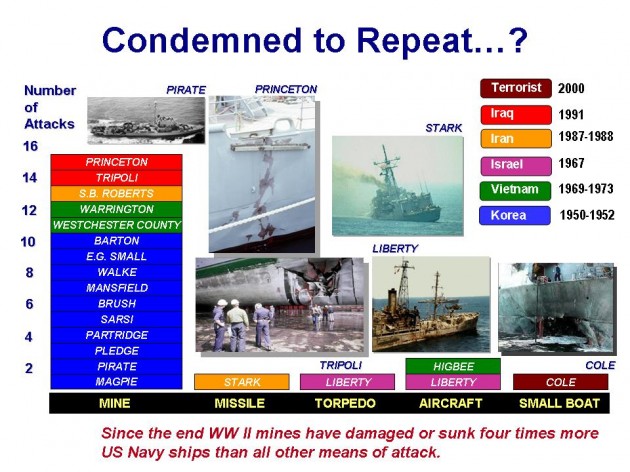

This is the first of three stories on the crucial but neglected question of sea mines and how well — or not — the United States manages this very real global threat. Since World War II, mines have sunk or crippled 15 US Navy ships, more than all other weapons put together. Like roadside bombs on land, sea mines are a cheap way to undercut American might: A single $25,000 Italian-made Manta mine crippled the $1 billion destroyer Princeton in the first Gulf War 20 years ago. To read the full series, just click here to see all three stories together. Read on. The Editor.

After decades of neglect, the Navy has started taking sea mines seriously. When Tehran threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz and cut off the flow of oil in 2011, the Pentagon reinforced the Bahrain-based Fifth Fleet with everything from 1980s-vintage Avenger-class minesweepers to unmanned micro-subs. The Fifth Fleet has hosted the three largest multinational minesweeping exercises in the Persian Gulf in living memory, the second set of wargames just nine months after the first, with the third and largest last November.

An Iranian submarine.

But the mine threat is much bigger than Iran. China boasts at least five times as many mines as Iran and considers them a crucial component of what it calls “counter-intervention.” In other words, mines, missiles, and submarines will work together to hold US ships at bay until China can reunify Taiwan by force – the contingency that still drives much Chinese planning – or perhaps grab disputed islets from the Philippines and Japan. (American experts call this “anti-access/area denial” and the US counter to it “Air-Sea Battle”).

The Chinese have been taking mine warfare seriously since at least the 1990s, even as the US let its mine-clearing force decline. “During the First World War, the German submarine force alone laid 11,000 sea mines,” Chinese author Ren Daonan noted approvingly in a 1998 article. “German submarines even dared to lay 58 mines along the Atlantic coastal littoral of the United States, sinking or damaging six American ships, thus achieving the utmost result.” Repeating the feat during World War II, “German navy submarines [laid] mines along the American coast, forcing the closure of 6 American ports for between 6-8 days.” That impact may seem modest – until you consider the consequences of the US Navy taking an extra week to sail from Pearl Harbor, San Diego, or Norfolk, Va. in the midst of a crisis.

Then there’s the lethal example the United States itself set in World War II, Daonan noted: “In the course of Operation Starvation, the US Army Air Force relied on B-29 bombers to plant 12,135 mines in Japanese waters” in just six months. Along with another 12,000-plus mines laid by US and British submarines, these air-dropped mines cut Japan’s sea lanes and crippled its war economy. Taiwan and Japan’s disputed Senkaku Islands, it just so happens, are well within range of Chinese bombers operating from the mainland.

While China is the clear up-and-comer in the global mine warfare game, however, they are not yet the champion. That would be Russia, the country that invented the standard modern mine more than a century ago and which still has the world’s largest arsenal of naval mines.

No wonder that one of the long-standing task forces in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization is the Standing NATO Mine Counter-Measures Group 1, which has patrolled the Baltic since 1973. What’s more, for most of the last decade, NATO and non-NATO minesweepers have been quietly convening in the Baltic for an annual exercise called Northern Coasts.

This year’s wargames weren’t driven by current events, emphasized the Finnish commodore in charge. Finland and Sweden — two non-NATO countries that have long, unhappy histories with Russia — now participate in Northern Coasts along with 11 NATO nations, bringing together a total of 57 ships, 20 aircraft, and over 3,000 personnel.

“The current situation in Ukraine and in Europe in general had no influence on this exercise because the planning of this exercise started a year ago,” Juha Vauhkonen, the No. 2 officer in the Finnish navy, told me in a phone call. But the Russians are watching. “That’s very natural that they are observing this exercise,” the commodore said. “They are observing but not interfering.”

That said, there’s no reason to be sanguine about Russian minelaying in either the Baltic or the Black Sea. While the Russian Navy is “a shadow” of its Soviet self, according to naval analyst Scott Truver, “I think they have a good capability to put weapons in the water both overtly and covertly,” for example using submarines or civilian boats.

For now, however, the mines to worry about in the Baltic are the estimated 80,000 left over from the two World Wars. Some are still live: As recently as 2005, one killed three Dutch fishermen — a murderous reminder of how deadly mines can be, and for how long.

Mines have sunk or damaged 15 US Navy vessels since 1945, more than all other causes combined. (Image by Scott Truver).

How Do I Sink You? Let Me Count The Ways

There is one big difference from World War II: The modern mine threat is much more sophisticated.

Today, stealthy mines made of fiberglass in sonar-deflecting shapes lurk amidst the clutter of the sea floor. There are buried mines covered by layers of sand, mud, and silt that no sonar currently in service can penetrate. There are “rising mines” that wait in deep water for a ship to pass overhead, then ascend until they’re within range to fire a torpedo: Russia has one that fires a version of their supersonic, supercavitating Shkval. There are reports that China is working on an anti-aircraft mine that can detect a low-flying helicopter – one towing minesweeping gear through the water, for example – and launch a missile at it.

There are mines activated by a ship’s magnetic field, by the sound of its propellers, by pressure differentials in the water as a ship passes overhead. There are mines that detect all of the above, then cross-check between different types of sensors to make sure they’re not fooled by a decoy. There are mines smart enough to distinguish different kinds of ships and only wait for a chosen target — only oil tankers, for example, or only aircraft carriers. There are even rumors of Chinese and North Korean mines with nuclear warheads.

“A recent [Chinese] article claims that China has over 50,000 mines [in] over 30 varieties of contact, magnetic, acoustic, water pressure and mixed reaction sea mines, remote control sea mines, rocket-rising and mobile mines,” Naval War College professors Andrew Erickson, Lyle Goldstein, and William Murray say in a 2009 study. But mine warfare expert Scott Truver thinks that estimate is way too low: He says the Chinese may have 100,000 mines (more on Truver’s numbers in a moment).

Iran’s inventory is much smaller – estimates vary wildly from 1,000 to 20,000 – but the area it must cover, the Strait of Hormuz, is also much smaller than the West Pacific. Like China, Iran has mix of mines of different types that can complement each other in lethal ways. “They thought about it when they bought those mines, because they create problems all the way down through the water column” from the surface to the bottom, said retired Navy captain Bob O’Donnell, a veteran minesweeper.

But the problem is not limited to those two countries. “Across the world these days,” said Capt. Frank Linkous, a Navy mine warfare official, “the threat exists from the low end – you know, World War I technology – to some more sophisticated mines[:] Mines that can drift and reposition, mines that oscillate [i.e. change the depth at which they float], mines that enhance their burial in the ocean bottom” by digging themselves in deeper. Some mines float just below the surface and blow holes in the hull of a passing ship. More massive mines lurk on the sea floor, then explode so powerfully that they break the keel of a vessel overhead, snapping its steel spine.

In spite of all this murderous innovation, however, the biggest danger remains a design perfected in 1908: the old-fashioned “moored contact mine,” the familiar spiky black ball. It’s called the M-08 after the year it was introduced by Russia – not the Soviet Union, mind you, which it predates by nine years, but the Russian Empire of Tsar Nicholas II.

In the century since, the M-08 has been so widely exported and imitated that it is the most numerous kind of mine by far. They are crude weapons. They have to be anchored on the sea floor, and the mooring chain limits them to shallow waters, at most 200 meters deep (about 650 feet). Their sensitive “horns” have to directly touch the hull of a passing ship for them to detonate, and it is fairly easy to destroy any one mine. But quantity has a quality all its own. M-08 clones are cheap, they’re common, and you can lay them in such large numbers that, crude as they are, they’re a laborious, dangerous nightmare to sweep.

A version of the classic M-08 mine, now over a century old.

How Many Mines?

So how many mines are out there, anyway? No one knows. When Adm. Gary Roughead, then Chief of Naval Operations, declared in 2009 there are one million mines worldwide, he was almost certainly rounding up. An online Navy primer says “more than a quarter-million.” Some estimates range as high as 750,000. Those are huge figures with a huge range of uncertainty.

Individual nations’ inventories are hard to nail down as well. For Iran, said Scott Truver, “I’ve heard as low as a thousand and as high as 6,000 mines.” Many of those are plain old M-08s, but others – some homemade, some imported from countries such as China – are sophisticated, smart, and stealthy.

Another expert, Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, writes that Iran has “over 3,000 devices” of all types but cautions in one study that “some reports put the total as high as 20,000, including 5,000 bottom-[lurking mines] and smart mines.”

Even that high-end estimate for Iran, however, is still dwarfed by figures for other potential adversaries. “North Korea has roughly 50,000,” Truver said. Northern mines damaged or destroyed ten US ships in the Korean War and delayed an amphibious landing at Wonsan so long that ground troops marching overland got there first. Fumed one Navy admiral at the time, Alan “Hoke” Smith, “We have lost control of the sea to a nation without a navy.”

China has 80,000 to 100,000, Truver estimated. Russia inherited a Soviet inventory estimated at “upwards of 250,000,” Truver said, “[but] that might be something of an exaggeration.”

Why are mines so hard to count? Compared to other weapons, even sophisticated mines are easy to build and easy to hide once manufactured. “It’s not like an assembly line for F-35 aircraft,” said Truver. “These things are relatively easy to produce without people knowing what’s going on.”

In fact, for countries aiming to wage mine warfare, the hard part isn’t making lots of mines. It’s getting them in the water before the US Air Force and Navy shut you down. The best way to defeat a minefield is to keep the mines out of the water in the first place. How the US can do that is crucial question we’ll examine in our next article.

Dear reader: We are planning to run the two other stories in this series on the next two Mondays. Let us know if you think this works, or if you’d like to see the pieces on a different schedule.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.