Let’s Get Digital: Hondo Geurts Wants Ships For Less $$

Posted on

The supercarrier USS Kennedy (CVN-79) under construction at Newport News Shipbuilding in Virginia

SAN DIEGO: Newport News Shipbuilding is reaping “huge savings” on the next Ford-class carrier, the Kennedy, through “creative” use of digital models instead of paper plans, the new head of Navy acquisition told reporters today. It’s an approach that can increase efficiency and reduce costs on all big Navy programs, said assistant secretary James “Hondo” Geurts.

Geurts also plans to

- increase the percentage of Navy contracts that go to small businesses,

- devolve decision-making authority on programs to lower levels,

- free smaller programs from obtrusive bureaucratic oversight originally intended only for mega-projects, and

- encourage risk-taking at all levels,

he told the AFCEA-USNI WEST conference here. I’d sum up his strategy in three concepts (my words, not his): decentralize, differentiate, and digitize.

James “Hondo” Geurts

Decentralize

Over the years, more and more authority over major defense programs got concentrated in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, specifically the undersecretary for acquisition, technology, and logistics (ATL). Congress has ordered the ATL job be broken up and devolved key authorities back to the four armed services.

Ellen Lord

The current (and last) undersecretary for ATL, Ellen Lord, has pushed that further, Geurts told the conference: She’s given him “milestone decision authority” — whether to let a program proceed from concept to R&D, from R&D to design, or from design to production — on “all but two” of the Navy’s largest programs, known as ACAT Is. (OSD retains milestone decision authority over the high-stakes Columbia-class nuclear missile submarine and the chronically controversial Littoral Combat Ship).

Now Geurts wants to decentralize and devolve authority within the Navy, he said. He’s giving Program Executive Officers more power over ACAT II programs and pushing those PEOs to devolve key decisions over ACAT IIIs and smaller to their subordinates in turn.

Given more leeway, some of these more junior, less experienced acquisition officials will probably screw up, Geurts admitted. But it’s better they make mistakes and learn from them when they are junior officials, managing smaller programs, he said, rather than micromanaging them until they are promoted to run mega-programs and screw up those.

“Quite frankly,” Geurts told the conference, “if you’re a new program manager and it’s your first program, I would rather have you have all the authority and if you’re going to misstep, misstep down at that lower level, where you can learn from it… than give you your first chance to do that at a high level on a big program where we can’t afford to misstep.”

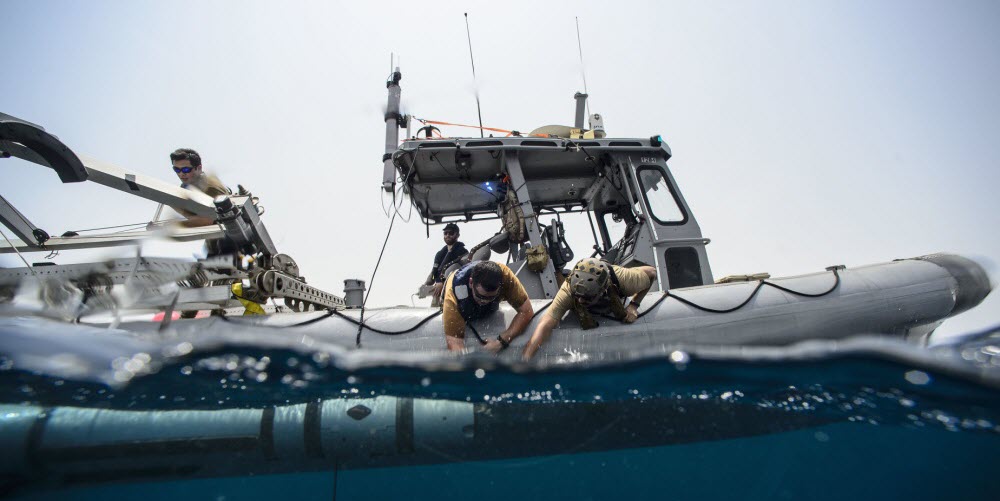

A Navy mine warfare team launches a unmanned underwater vehicle from their 11-meter inflatable boat. The Navy must buy everything from small craft and drones to supercarriers.

Differentiate

Devolving authority over smaller programs to lower levels is one way Geurts wants to treat different programs differently. One size definitely doesn’t fit all, but the bureaucracy tends to act as if it does, which is why so many programs large and small ended up under the direct oversight of the Office of the Secretary of Defense. But it’s ridiculously inefficient to impose (for example) the same kinds of stringent oversight on a small software upgrade as on aircraft carrier construction.

Special Operator on horseback in Afghanistan

“In the Department over time, we decided what was good for a big, hairy ACAT I program was good for an ACAT IV program,” Geurts said. “You’re seeing me completely flip that model….. If it takes me as long to write a contract for a $50,000 or $100,000 SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) as it does for a $100 million development effort, that probably doesn’t make sense.”

The need to differentiate is a particularly important insight coming from Geurts, who made his name at Special Operations Command, which operates on a much smaller scale than the Navy. SOCOM acquisition has a reputation for efficiency, speed, and innovation, but then again it doesn’t have to buy $13 billion aircraft carriers or $121 million fighter jets.

“Certainly there’s a scale difference,” Geurts acknowledged. “Some things take a long time and they should take a long time, because we’re going to have them around for 40 or 50 years, but that doesn’t mean that every piece of gear on that ship needs to be built for 50 years.” Capital ships like aircraft carriers will stay in service half a century, so it’s important to take your time and get it right. But much of the technology on those ships — sensors, weapons, communications — will get updated many times over the ships’ life, and the Navy can separate out those upgrades and handle them in a faster, streamlined, process that can tolerate more risk.

But how do you fix the mega-programs themselves? That’s the question I asked Geurts when he spoke to reporters after his talk to the conference. His immediate answer: Let’s get digital.

Newport News workers build the future supercarrier USS John F. Kennedy (CVN-79)

Digitization

“What I would say on these big mega-projects is you’re starting to see the era of digital,” Geurts told reporters. “We’re starting to see on the second carrier, the second Ford (class) carrier, huge savings, and I think that’s just going to continue…. We had folks, workers that had been working on ships forever, starting to see this new technology and very creative on how to do things differently.” On Tuesday, Geurts explained, he had visited Newport News Shipbuilding in Virginia, the only shipyard on the planet that can build a nuclear powered aircraft carrier, and been very impressed by the technology and creativity they were applying to the construction of the future USS John F. Kennedy (CVN-79).

Graphic courtesy of the office of Sen. McCain

What Geurts didn’t say that Breaking Defense readers will know is that Newport News and the Navy are under intense congressional pressure to keep the cost of Kennedy down. The JFK will be the second ship of the Ford class, the first new aircraft carrier design after four decades of Nimitz-class ships, and the first of the new class, the Ford herself, went badly over budget and behind schedule. Something has to change.

Something is changing, Geurts said. Putting together his comments with those of other Navy officials at the conference, the idea is to create a detailed digital model — down to individual pipes and specific versions of software — of the ship, aircraft, network, or other system. The model is created in the earliest phases of design and then updated through construction, fielding, and maintenance. Production managers, for example, can experiment with different ways of ordering assembly in the digital world before committing to a particular layout in the real-world shipyard. Instead of bulky blueprints and heavy jigs, shipyard workers can follow laser pointers to drill precisely at the right place and then check their work against an augmented reality display overlaid on the real-world object. Later on, inspectors can use the digital model figure out exactly what and where they need to check, and repair teams can use it to find exactly what they need to fix.

“You start seeing now a ship that we have a full digital model of…. and that enables you to do some really intriguing things on planning (and) inspection as well as on repair,” Geurts said. “We’ve got to figure out how to get those kinds of technologies in so we can drive out the cost.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.