Let Leaders Off The Electronic Leash: CSA Milley

Posted on

An Army captain briefs the Chief of Staff, Gen. Mark Milley, at Fort Hood.

ARMY & NAVY CLUB: To win the fast-paced and brutal battles of the future, Army generals must let their subordinates off the leash, the Chief of Staff said here yesterday.

“What we do, in practice, is we micromanage and overly specify everything the subordinate has to do, all the time,”Gen. Mark Milley told an Atlantic Council forum here. “It might be an effective way to do certain things. It is not an effective way to fight.… You will lose battles and wars if you approach warfare like that.”

Milley’s push for more initiative could have profound effects on tactics, training, and technology — if he can overcome the Army’s incredibly deep-rooted culture of micromanagement. It’s an institutional dysfunction further enabled in recent years by omnipresent electronic communications, communications we’ve come to rely on but which a sophisticated adversary could cut off, forcing low-level leaders to fend for themselves.

Army command post

“There’s a balance in there you have to achieve,” Milley said, “(but) I think that the pendulum swung too far. I think we’re overly centralized, overly bureaucratic, and overly risk averse, which is the opposite of what we’re going to need in any type of warfare, but in particular the warfare that I envision. We are going to have to empower, decentralize leadership to make decisions (when) they may not be able to communicate with their higher headquarters.”

“So we have to practice what we preach,” Milley continued. “We preach mission command” — in which superiors give subordinates clear objectives without prescribing how to achieve them — “but we don’t necessarily practice it on a day to day basis in everything we do.”

A faculty member at the Army War College put it more bluntly: “Mission command… because of technology, we have lost the art of it,” the scholar told me last week. “I have had four-star generals who (said), ‘I want the (radio) frequency to the platoon that’s out there’… as we watched it on Predator porn up on the big screen. But I’ve also had a commander who said, ‘hey, this is the sandbox I want you to play in. Figure out how you’re going to do it.'”

“I personally have seen examples four-stars doing quite literally the extremes of both of those,” the War College scholar said. “I think it is largely personality-driven.” Officers burned by subordinates’ mistakes in the past — and a single soldier’s DUI can compromise his commander’s career — can become neurotically controlling.

Gen. Mark Milley

Milley promised change. “It starts with me and the Secretary of the Army, it goes down to our general officer corps,” he said. “We must trust our subordinates, so you give them the task and give them the purpose and then you trust them to achieve the intent.”

“If they achieve it, great, hang a medal (on them),” Milley said. “If they fail, you fire them.”

That’s sort of a mixed message, a little like “junior officers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your jobs.” It doesn’t align with the rhetoric about empowerment out of Silicon Valley or many civilian defense officials, which emphasizes “freedom to fail”: giving subordinates leeway to learn by trial and error. Of course, with lives at stake, the uniformed military has cause to be more cautious.

“We want to encourage the freedom to fail, except it depends on the failure,” Milley said, to laughter. “If you have a failure in the Battle of the Bulge or at Normandy, hey, I’m sorry… winning matters, victory matters. (But) if you fail in less important things, that’s different, there are teachable moments.”

Milley’s answer left questions hanging. “How much failure are we willing to underwrite?” said a second War College faculty member. “We haven’t really come to terms with that. That’s never going to be codified — that’s a judgment call.”

“A Different Type of War”

When it comes to initiative, the Army has been schizophrenic for a century. Its roots go back to militia companies that elected their own officers. Then a bureaucratic, top-down War Department became essential to manage the sheer mass — of men, of armaments, of supplies — that won the Civil War and the two World Wars. The large standing army of the Cold War and the information-age army of the post-9/11 wars only reinforced this trend.

Forward Operating Base (FOB) Hammer, typical of the extensive infrastructure set up in Iraq.

In Afghanistan and Iraq, US forces usually operated out of large Forward Operating Bases, with lavish logistics — ammunition, fuel, food, showers, even Pizza Huts — and well-established communications networks. A GPS system called Blue Force Tracker pinpointed subordinate units on their commander’s screen, drones watched their operations from overhead, and radios kept them in constant contact with their commanders. Fear of causing civilian casualties, which would inspire more insurgents and undermine support back home, led to leaders imposing strict rules of engagement. The complexity of the conflict did give many junior leaders room to exercise initiative, from calling in close air support to negotiating with village elders. But logistics and networks tethered every tactical unit to higher command.

High-tech adversaries, however, have studied how to cut those lifelines. Even the Taliban managed to tap into an improperly secured video feed from Predator drones, but Russia and China have legions of hackers to attack American code. They have well-equipped electronic warfare units to jam American transmissions — or triangulate their sources for bombardment. They have their own drones to pinpoint targets and precision weapons to strike them. Against such enemies, it’s suicidal to cluster on big, static bases, send out long convoys of supply trucks, or transmit electronic signals non-stop.

Russia’s new T-14 Armata tank on parade in Moscow.

“We have got to recondition ourselves to a different type of war,” Milley said. Since 9/11, we’ve been doing counterinsurgency and counterterrorism against relatively lightly armed and low-tech foes, he said, but “there are many other types of war, and the one that is perhaps most difficult and challenging — and a very real possibility — is a larger war against a near-peer or a much more capable state adversary… in very rugged, urban, complex terrain. In that environment…if you’re stationary, you’ll die. Your logistics lines and your lines of communications are going to be under intense stress, (and) the electromagnetic spectrum is going to be at least degraded if not completely disrupted….and yet you’re still going to have to fight and you still have to win.”

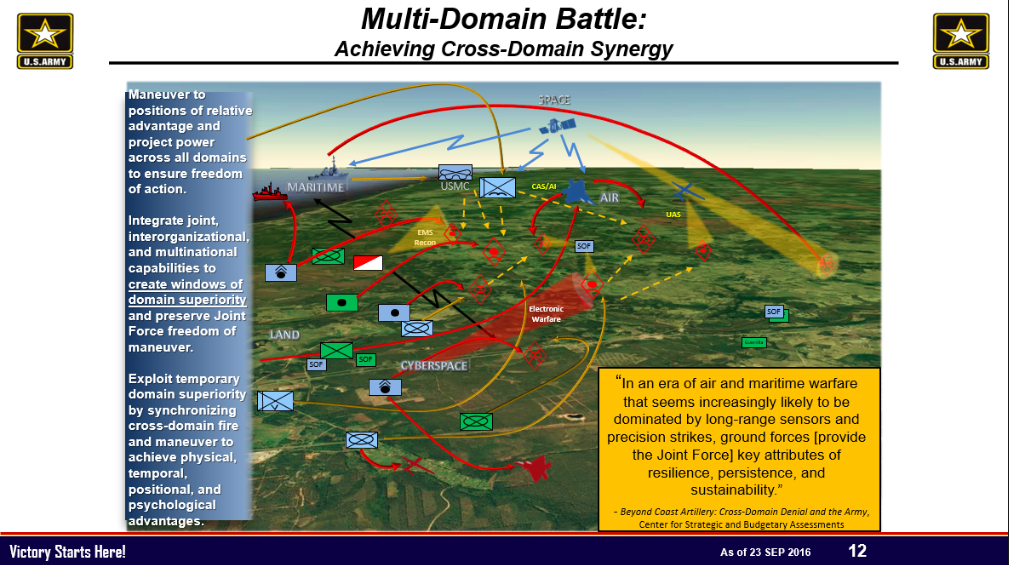

To prevail, the Army wants to fight what it calls a Multi-Domain Battle, which among many other things requires small tactical units to disperse and keep moving even when cut off — both physically, behind enemy lines, and electronically, by jamming or hacking of communications networks. The ever-increasing urbanization of the planet — by 2050, Milley said, 90 percent of Earth’s eight billion people will live in cities — further isolates small units, with roads and buildings channeling them away from friendly forces and concrete structures blocking radio communications. In such chaotic combats, junior officers must be able to operate with assured supply lines or constant supervision.

“Multi-Domain Battle (requires) mission command. What underpins mission command is a term called ‘disciplined initiative’ — and therein lies the rub,” said the second War College scholar. “(If) communications are cut off, he exercises disciplined initiative… and it goes wrong — too many casualties, a friendly fire incident —are we willing to underwrite that person?”

“We’re still grappling with that,” the scholar said. “We don’t like failure, we all know that, and we tend to punish people, (but) it’s easy to second-guess something in an office later.”

At the Atlantic Council event, both moderator Nora Bensahel and I pushed Gen. Milley on this question. “If you fail to win a battle… then you should and rightfully so be held accountable,” the Chief of Staff said. Even outside of battle, he said, “we don’t want a zero defects organization — I don’t believe we have one, by the way — but there are some things that are zero defects, there are some things like, morality, personal conduct.”

At the Atlantic Council event, both moderator Nora Bensahel and I pushed Gen. Milley on this question. “If you fail to win a battle… then you should and rightfully so be held accountable,” the Chief of Staff said. Even outside of battle, he said, “we don’t want a zero defects organization — I don’t believe we have one, by the way — but there are some things that are zero defects, there are some things like, morality, personal conduct.”

“I’m sorry, life is hard and it’s way harder when you’re stupid,” Milley said. “If you do stupid, immoral, illegal, unethical things, then you’re gone. There is no second chance.”

On the other hand, Milley said, disobeying orders may be tactically and ethically imperative if the situation changes in ways your superiors didn’t anticipate. If an officer has orders to destroy the enemy on Hill 101, but when he gets there, the enemy’s actually on Hill 102, he should just go take Hill 102, Milley said by way of example: “He shouldn’t have to call back and say, ‘hey boss, mother may I, can I go to over to 102?”

“This is a really controversial concept,” Milley said, “but a subordinate needs to understand they have the freedom and they’re empowered to disobey a specific order, a specific, specified task, in order to accomplish the purpose. It takes a lot of judgment.”

“This has to be disciplined disobedience to achieve a higher purpose,” Milley emphasized. “Stupid chip on the shoulder disobedience— you’re going to get hammered for that.”

The great unanswered question, of course, is whether senior officers can consistently tell the difference — and whether junior officers will trust them to get it right.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.