LeoLabs’ New Radar Tracks Tiny Space Debris

Posted on

LeoLabs’ “Kiwi Radar” in New Zealand can detect space debris the size of a marble

AUSA 2019: LeoLabs today announced a unique radar for tracking space objects, based in New Zealand to improve monitoring of satellites and debris over the Souther Hemisphere — where even DoD has limited satellite tracking ability.

“It’s got a number of ‘firsts’,” CEO and co-founder Dan Ceperley told Breaking D, including being “the first phased array radar for space in the Southern Hemisphere, where collision prevention isn’t as good, especially over the South Pole.” The radar is based in the Central Otago region (famous for its pinot noir wines) of New Zealand’s South Island.

The “Kiwi Space Radar”, unveiled today at the annual conference of the Association of the United States Army, also is the “first commercial radar to be able to detect objects down to 2 centimeters in diameter in Low Earth Orbit,” Ceperley added. That is, about the size of a marble. Most current ground-based space tracking radar can only see objects bigger than 10cm, about the size of a softball, in LEO — including those operated by the US military to provide space situational awareness (SSA).

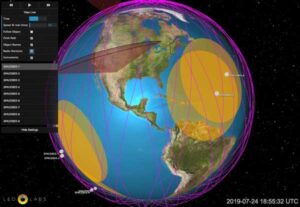

Phased array radar — unlike classic radar using large dish antennas — can rapidly switch point of view from one side of sky to other, he explained. LeoLabs can track up to 1,000 space objects per hour, and thus serve to cue other radar that can then “zoom in” on objects of interest. “We can help establish what is benign,” Ceperley said, and thus “power defense users” and “provide independent confirmation” of possible collisions or malicious activity.

LeoLabs, a Silicon Valley startup founded in 2016, intends to create a network of six radar. The next three will be located near the equator, in the far north and in the far south to ensure global coverage. Ceperley said that the company isn’t ready to announce the exact locations, but explained that they are looking at areas that are geopolitically stable for US company investment, and can provide enough support for radar operations such excellent Internet connectivity.

However, LeoLabs doesn’t sell radars — it sells access to its data and analytical products via subscriptions. The company has four different sets of customers, Ceperley said, including defense organizations, regulators, satellite operators (including NASA) and insurers.

The firm already is working with the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) and the Defense Innovation Unit since 2017 under a program called CAMO, (Commercially Augmented Mission Operations). While Ceperley wouldn’t disclose the size of the contract, he explained that LeoLabs is participating in AFRL’s effort to explore how commercial SSA services “can augment and help improve DoD’s understanding of space.”

Maj. Gen. Kim Crider

Back in April, Air Force acquisition head Will Roper told Breaking D that LeoLabs, ExoAnalytic Solutions, Numerica and Rincon all are providing their space data and analytical toolsets to the Air Force as it experiments with how to integrate a wide variety of data sources, and use agile software development, to improve its SSA and battle management systems.

One facet of the effort is called the Unified Data Library (UDL), which Maj. Gen. Kim Crider, the data integration guru at Air Force Space Command (AFSPC), says is “an enterprise data repository for managing access, integration and dissemination of data across multiple levels of security.” In turn, the UDL is used to inject data into AFSPC’s Enterprise Space Battle Management Command and Control (ESBMC2) system that also will ingest information from the Intelligence Community.

But the company has a broader mission, according to Ceperley: “to drive a new era of transparency in LEO.” “There just is not a lot of data about the risks in LEO,” he explained at a time when space activity in the region (from about 100 kilometers to 2,000 kilometers above sea level) is exploding. Ceperley said he’d like to see the data generated by LeoLabs’ radar network help set a goal to “contain the debris problem” to some optimum level, and allow operators to figure out how to adjust their activities to do so.

LeoLabs’ LeoTrack for monitoring smallsats

Further, mindful that many new operators are not rolling in financial capitol or years of expertise, one of LeoLabs’ newest services, called LeoTrack and launched in August, is tailored for operators of one to five satellites, and provides an option to buy off-the-shelf navigation data so the operator doesn’t have to understand how to equip the satellite to do so. According to a LeoLabs’ press release, the LeoTrack offers “satellite operators a full range of monitoring capabilities, including precision tracking of satellites, orbital state vectors, predictive radar availability, scheduled passes, and real-time orbit visualization for constellations as well as individual satellites.” Ceperley said the service costs about $2,500 per satellite per month, which in the scheme of SSA services market is pretty low.

In addition, LeoLabs is working closely with the New Zealand government under its ground-breaking SSA and space traffic management (STM) program that will allow the New Zealand Space Agency to track every satellite launched from its territory, monitor their health, keep an eye out for potential collisions, and ensure that all operators are following licensing rules regarding satellite disposal and debris mitigation. The cloud-based Space Regulatory and Sustainability Platform (SRSP) uses LeoLabs radars, as well as analytical tools such as mapping software and conjunction prediction.

Ceperley sounded almost giddy about the potential of the New Zealand program to safeguard the future space environment and change the way governments regulate the space industry. “They are the first regulators to keep a close eye on activity in orbit,” he said, noting that most government license processes, including in the United States, focus only on pre-launch licensing. Using the SRSP platform, he said, New Zealand will “develop an understanding about what’s normal behavior in space and what not,” and in turn be able to “drive drive the discussion, using actual data, about what’s responsible or not,” and to “lead the response to to next the next big crash.”

Indeed, according to several space analysts, the New Zealand program puts them far ahead of any other country in attempting to solve the STM problem, despite the Trump Administration’s push to lead the rest of the world in setting space norms and best practices.

The administration’s efforts, embodied in Space Policy Directive-2 (SPD-2) on licensing for commercial space and SPD-3 on STM, are stalled due to variety of internal bureaucratic as well as congressional food fights. As we reported a few weeks ago, the interagency task force to update US space debris mitigation rules hit an impasse on Sept 18, putting the dispute on the table for the National Space Council to sort out.

Meanwhile, the long-awaited Notice of Public Rule Making (NPRM) designed by the Commerce Department to streamline licensing for commercial remote sensing operators has stalled amid interagency disagreement and industry pushback. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross in August said the rules would be out by the end of October, but source say as of now the rule package remains blocked by interagency squabbling.

Finally, Congress has steadfastly refused to provide authorization or funding to give Commerce the primary role in regulating the commercial space industry, and in becoming the agency to lead a civilian SSA service — taking over the job of helping commercial and foreign operators safely control their satellites and avoid collisions from the newly created Space Command.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.