LCS Cut Ripples Through Navy’s New 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

Posted on

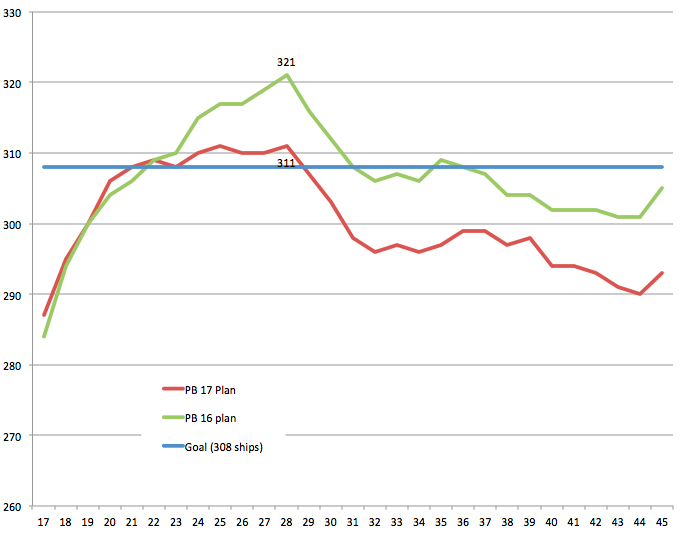

Total fleet size per year in current (PB 17) and last year’s (PB 16) 30-year-shipbuilding plan

WASHINGTON: Defense Secretary Ashton Carter cut the Littoral Combat Ship program by 12 vessels last fall, but the surface fleet will feel the impact for decades. The long-term ramifications are laid out in detail by the Navy’s forthcoming 30-year shipbuilding plan, excerpts of which were obtained by Breaking Defense.

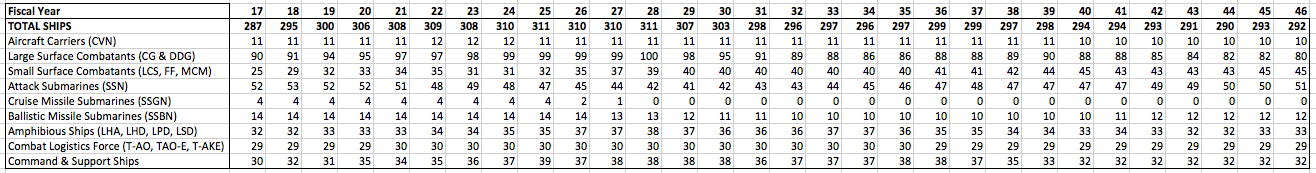

Last year’s 30-year plan projected the Navy would meet or exceed its goal of 308 “battle force” ships in twelve years (2022-231 and 2035-2036), peaking at 321 ships — which Carter called excessive — in 2028. By contrast, and entirely as a result of the LCS cut, this year’s projection is that the Navy will fulfill the 308-ship requirement in only eight years, 2021-2028, peaking at 311 vessels — just three ships above the goal.

What’s more, Navy leaders have more than hinted that 308 is not enough and their ongoing Fleet Structure Assessment — the first full review since 2012 — will raise the requirement to reflect the increased threat from China, Russia, and the Islamic State. If the goal goes up as little as four ships, to 312, the current 30-year plan will never meet it.

“I would bet a paycheck it’s going to be a number greater than 308 ships,” the Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. John Richardson, said at last week’s McAleese/Credit Suisse defense conference. “We’re cooking on that right now,” he said, with the new Force Structure Assessment probably coming out “this summer.”

For now, though, the Navy is still working off the 308 number, which, Richardson noted, includes 52 Littoral Combat Ships — not the 40 the program was cut to. Some documents cite a 40-LCS “warfighting requirement,” but that by definition does not consider demands for peacetime presence, which for an auxiliary like LCS is easily higher .

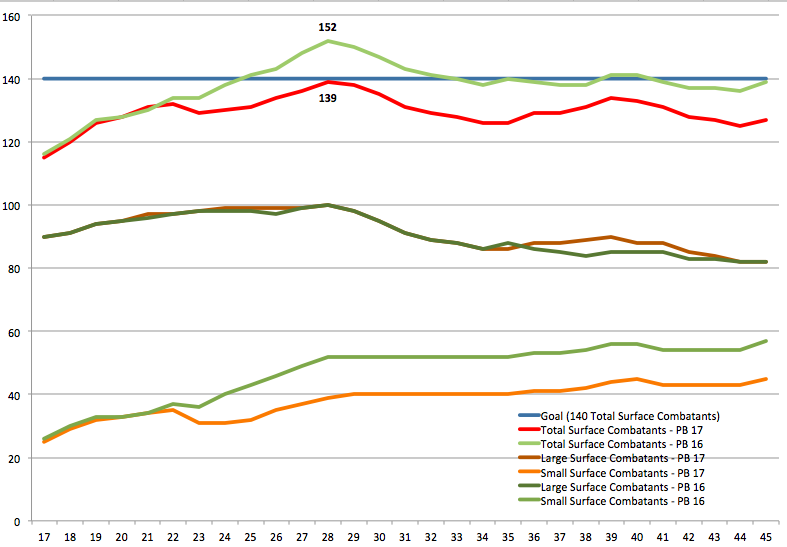

Large, Small, and total surface combatants in current (PB 17) and last year’s (PB 16) 30-year shipbuilding plan.

As part of the current 308-ship total goal, the Navy has a requirement for 140 surface combatants of all types, from 3,500-ton LCSs to 9,600-ton cruisers. Back in February Deputy Defense Secretary Bob Work assured me that the Navy would still meet that 140 goal even with fewer LCSs, because it would get more large ships such as destroyers. It turns out that’s not exactly true. (It’s worth noting Work may well have seen an earlier draft of the plan when he spoke to me). The new plan peaks at 139 surface combatants in 2028 and drops back down the next year. The old plan, with the 12 LCS in it, would have stayed at or above the 140-ship goal for 12 years.

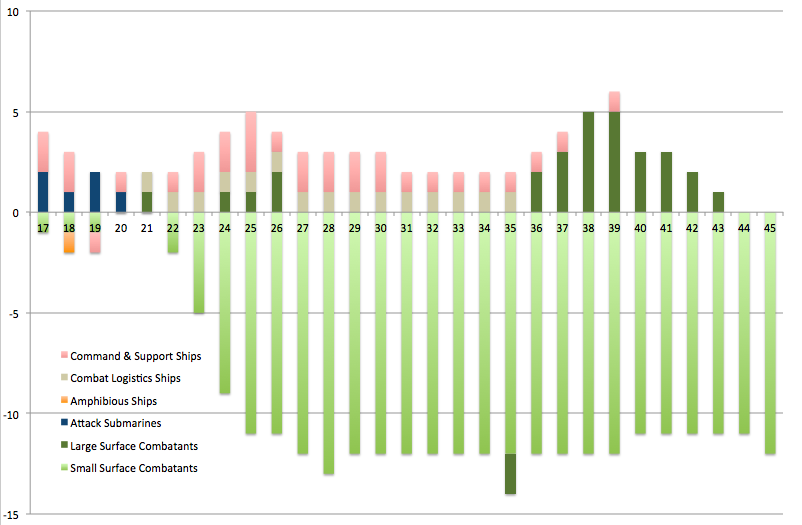

The new plan does add more large warships to the fleet compared to the old, but most of them come in the 2030s, when an as-yet-undesigned “Future Large Surface Combatant” enters the service. It also increase the number of attack submarines, but only by two and only in the near term. Other types of vessel such as logistics, command, and support ships fluctuate slightly between the two plans. The figures for the ultra-expensive pillars of naval power — aircraft carriers and ballistic missile submarines — stay the same, although naval leaders continue to warn they can’t afford the Ohio Replacement Program sub without budgets well above current levels.

Differences in number of ships, by type, between current (PB 17) and last year’s (PB 16) 30-year shipbuilding plan.

So the difference between the current plan and the old one is almost entirely driven by the removal of 12 Littoral Combat Ships. LCS critics — and there are many — would say good riddance: The small vessels are too fragile and undergunned, and while they’re a fifth the price of an Arleigh Burke destroyer, they’re much less than a fifth as good. Perhaps. But the question is, good for what? Appropriately configured LCS will make up all the future navy’s minesweepers and a good chunk of its sub-hunters, both missions where multiple small ships covering lots of ground (or rather water) can accomplish more than a single large vessel, however capable. The Navy’s also working to upgrade the LCS’s much-criticized anti-ship firepower.

The upgraded “frigate” LCS with these added weapons won’t begin construction until 2019. But when launched a few years later, it is expected to stay in service for a quarter century. The larger destroyers last 30 to 40 years; the giant aircraft carriers, fifty. It’s these long, predictable lifespans that make it possible to write a 30-year shipbuilding plan in the first place. Ships take long enough to build that for the next 5-10 years, we can be pretty confident what we’re getting, because those vessels are already under contract; but even beyond that, we know what we’ll be giving up. Today’s fleet is still living off ships ordered in the Reagan build-up. The fleet we plan today — with however many Littoral Combat Ships — is the fleet we’ll have to live with for decades.

“Ships are going to come out of service at the end of their life at pretty much the same rate they came into service,” said Richardson. “When you don’t pay attention to the entire differential equation, if you will…you might peak at a particular level but you’ve got to think further downstream as to what…maintains that.”

Summary Tables from current (PB 17) 30-year shipbuilding plan

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.