Kill Army Helo Upgrades & Build Super Chopper: Bell V-280 Exec

Posted on

Bell V-280 Valor Joint Multi-Role Demonstrator (CGI graphic)

AMARILLO, TEX.: Bell Helicopter is so confident in their new V-280 tilt-rotor prototype that they want the Pentagon to accelerate the Future Vertical Lift program – which they think the V-280 will win – by “five to eight years.”

[Click here for our head-to-head comparison of the V-280 and its rival, the Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1]

A UH-60 Black Hawk takes off after unloading soldiers during an air assault exercise in Germany.

That would pull production of the first FVL variant, a faster and longer-ranged replacement for Army UH-60s and Marine UH-1s, from the 2030s to as early as 2025. To pay for the earlier start, Bell program manager Chris Gehler told reporters here yesterday, the Army should cancel its $10 billion Improved Turbine Engine Program (ITEP), which aims to boost existing helicopters’ power by 50 percent and reallocate the money to the all-new FVL.

Money will be tight in the 2020s, even after the Budget Control Act caps expire, because the Pentagon has pushed back many expensive modernization programs whose bills will be finally coming due, what insiders call a bow wave. That includes replacing all three legs of the aging nuclear triad with new weapons systems – the Air Force’s B-21 stealth bomber, the Navy’s Columbia missile submarine, and the Air Force’s new ICBM – as well as full-rate production of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

Buying FVL on top of all those programs will be tough, and cancelling ITEP will just be a down payment. Besides, even if the first FVL unit is ready for war – Initial Operational Capability – by 2030 as Gehler suggests, it will take decades to replace all the existing helicopters, so the ITEP investment in upgrading their engines would have a long time to pay off.

Marines train on a UH-1Y Venom — a radical update of the venerable Huey.

Gehler doesn’t deny any of that, but he thinks accelerating FVL is worth the price. Modern Russian artillery rockets have a longer range than Black Hawk helicopters, putting any base they could use at risk, he argues, so we need aircraft that can launch from further away. Anti-aircraft missiles keep getting better ranges, too, which forces helicopters to cross a deeper danger zone to reach their targets. Army aviators are relearning Cold War low-altitude tactics to stay below that radar, but Gehler doubts such “nap of the earth” flight can evade massed rifle fire of the kind that ravaged US Apaches near Najaf in 2003. Instead, he argues, you need to fly high, above most missiles’ range and at speeds that give them little time to lock on and kill you before you’re gone.

But you can’t make conventional helicopters much faster, higher-flying, or longer-ranged than they already are. Helicopter design is up against fundamental aerodynamic limits. The whole point of the FVL project is to find some revolutionary design that can transcend those limits. Bell argues their tilt-rotor technology is battle-tested and ready for that challenge – and that their rivals’ compound helicopter is not.

A V-22 Osprey tilting its rotors

The Tilt-Rotor Track Record

Until both prototypes are in the air and under evaluation by the military, no one can known whether Bell’s tilt-rotor technology or Sikorsky’s SB>1 Defiant compound helicopter is better. But Gehler does have one incontestable point in Bell’s favor: a track record. The V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor has been in service with the Marines and Air Force for 10 years now, with over 385,000 flight hours to prove the technology works in real-world military missions. The V-280, Bell says, will build on that experience and add numerous improvements, many of them simplifications of the V-22 design – a straight wing instead of a swept one, a tilt-rotor that only tilts part of the engine instead of the whole nacelle – that will increase reliability and reduce cost.

The Sikorsky-Boeing SB-1 Defiant concept for the Joint Multi-Role demonstrator, a predecessor to the Future Vertical Lift aircraft.

“When we started to design the V-280,” Gehler said, “we (had) hundreds of thousands of V-22 hours to look at and lessons learned.”

By contrast, all the compound helicopters to date have been technology demonstrators, not mass-produced combat craft. That doesn’t mean the Boeing-Sikorsky team can’t win this one. Theirs may be the technology whose time has finally come. But they do have a higher burden of proof that compound helicopters are not just feasible, but practical.

Boeing and Sikorsky don’t share Bell’s passion for accelerating FVL, either. They both build helicopters in current service with the Army – the Boeing CH-47 and AH-64, the Sikorsky UH-60 – so keeping those systems in service longer is a sure bet for their business. Replacing those current helicopters with FVL, by contrast, runs the risk that Boeing’s and Sikorsky’s products will be replaced by Bell’s.

Bell, meanwhile, is building AH-1Z and UH-1Y helicopters for the Marines, as well as the V-22 tilt-rotor, but in numbers much smaller than the thousands of aircraft the Army buys. It’s the Army that’s running the medium-weight (“Capability Set 3”) variant of FVL, and it’s the massive Army market that Bell is hankering for.

No wonder, then, that Bell is eager to accelerate FVL.

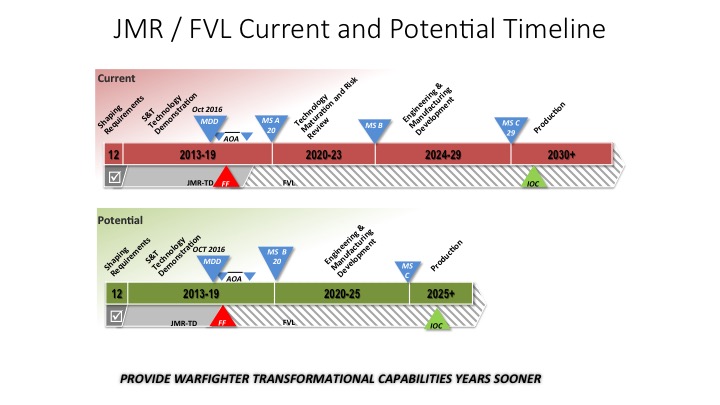

The Pentagon’s current timeline for Future Vertical Lift (top) and Bell Helicopter’s proposal to go faster.

No Shortcuts (We Promise)

Bell is not asking the Pentagon to take any shortcuts, Gehler insists: “It’s really about taking credit for all of this development and testing that’s already been done” – over 80 percent of it at Bell’s expense, not the government’s, he emphasized. “Does it make sense to do it all over again?”

In essence, Bell wants the Pentagon to count the dueling technology demonstrators, their V-280 Valor and the rival SB>1 Defiant, as full-up prototypes for FVL, allowing the winner to immediately begin designing the final production model. To put it in Pentagonese, the military would declare that the current Joint Multi-Role Technology Demonstrator (JMR TD) program also serves as the Technology Maturation & Risk Reduction (TMRR) phase of FVL, allowing FVL to proceed immediately to Milestone B and the start of Engineering & Manufacturing Development (EMD).

V-280 Valor under construction

That doesn’t cut out any steps, Gehler argued. To the contrary, the current demonstrator program is actually more comprehensive and rigorous than a normal program’s Technology Maturation & Risk Reduction. To start with, Bell and the Boeing-Sikorsky team are building and flying actual aircraft, in realistic conditions, instead of just doing simulations and computer models as in a typical TMRR. (Competing at least two prototypes is technically required but often waived). Bell is also putting the V-280 through “very similar, if not identical” testing to what they’d normally do for a production aircraft, not a prototype.

Cutting-edge computerized design – right down to projectors that overlay an image of where parts need to go on the actual aircraft – helped them put it together with unprecedented precision, Gehler and his colleagues said. When it came time to install the engines on the prototype, for instance, a process that usually involves lots of false starts, design tweaks, and minor changes to make things fit, the Army official who flew down to oversee the process booked his hotel room for a week. The engine was installed in six minutes.

The V-280 prototype is now complete and starting its ground tests. If the V-280’s flight tests go that smoothly, Bell will have a strong case that their technology is ready to do the Future Vertical Lift mission – and much sooner than the military plans.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.