Keep Ships Longer To Boost Fleet Size: 355 Ships By 2035

Posted on

WASHINGTON: The Navy can cut 20 years off the time to grow to its target of 355 ships, the service’s chief shipbuilder said today, if it invests more in maintaining and upgrading its current vessels so it can keep them longer. Instead of growing from 284 ships now to 355 in 2052-2055, the timeframe officials cited in the past, the Navy could reach its goal in 2032-2035, said Vice Adm. Thomas Moore, chief of Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA).

Admirals were already telling Congress that just building new ships faster was not enough if you retire old ships at the same rate. It’s a classic case of two steps forward, one step back. You get to 355 far too slowly to serve the new National Defense Strategy, with its emphasis on near-term great power competition.

“Even if you’re going to build at the maximum rate possible… based on the capacity we have today (and) when we take ships out service… we don’t get to 355 until 2052,” Moore said. “That’s not something you want to put on a bumper sticker.

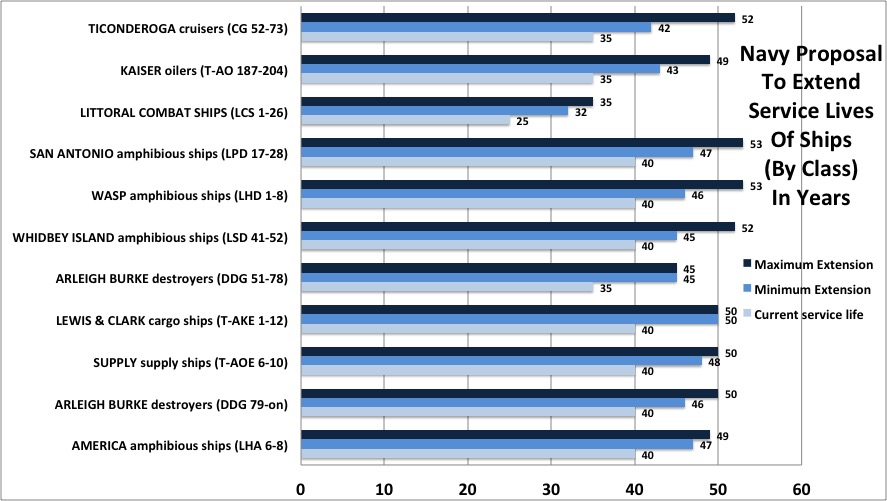

But if you also keep old ships longer, Vice Adm. William Merz testified to the House seapower subcommittee on April 12th, you can get to 355 “as quickly (as) the 2030s.” Merz focused on extending the service life of the Navy’s workhorse destroyers, the Arleigh Burke class, but a leaked April 25 memo from Moore proposed extending the service lives of 11 different classes of surface ship by 15 to 49 percent. Today is the first time we’ve seen such a senior officer give such a specific figure for reaching 355 ships faster.

Some of Moore’s goals are extremely ambitious, others less so:

- The memo proposes extending the service lives of aging Ticonderoga-class cruisers — which the Navy once argued weren’t worth the cost to keep in service — by 20 to 49 percent, which would keep some cruisers in service longer than the half-century span once exclusive to aircraft carriers.

- It proposes keeping Littoral Combat Ships, light vessels originally designed to last 25 years, for 28 to 40 percent longer, to as long as 35 years. That’s even though half the LCS fleet, the Independence class, have aluminum hulls instead of the Navy’s standard steel. (The Freedom variant has an aluminum superstructure but a steel hull).

- Support ships like oilers and cargo ships would go from the current 35 to 40 years, depending on the class, to 43 to 50 years. That means anywhere from a 20 percent increase (the most modest option on supply ships) to 40 percent (the most ambitious option on oilers), a wide range of variation.

- By contrast, amphibious warships, which carry Marines, their equipment, and their aircraft, would go from the current standard of 40 years in service to 45 to 53 years, depending on class. That’s a 13 percent to 33 percent increase, more modest than LCS or cruisers.

- The workhorse Arleigh Burke destroyers would go from the current 35 to 40 years, depending on the variant, to 45 to 50 years, a relatively modest 15 percent to 29 percent increase. These ships are famously rugged and wouldn’t cost most to keep in service longer, said retired Capt. Jerry Hendrix, but, as frontline fighting ships, they’d also need potentially expensive upgrades to combat systems like radars and computers.

Note all these are surface ships. The service lives of submarines are harder to extend, since their hulls undergo so much pressure and their reactor cores run out at specific times. But, retired submariner Bryan Clark told me there are five spare Los Angeles-class reactor cores that could be used to extend five old subs by a total of 50 years for the price of one new Virginia-class boat.

The fleet that would result from these service life extensions would have 355 ships, but not the exact 355 ships the Navy called for in its official Force Structure Assessment (FSA). There’d be more destroyers than the FSA called for and fewer attack submarines, in particular. But it would be a lot closer to the goal than the Navy could achieve any other way.

Devils In The Details

The Navy can definitely extend the service lives of many of its ships, Moore told the American Society of Naval Engineers (ASNE) this morning. “We’ve worked really hard over the last 10 months,” he said. “We absolutely can keep some of these things longer.”

“We keep carriers for 50 years (already),” he said. When we retire smaller ships like frigates, we often sell or gift them to friendly countries that proceed to keep them another 20 years, showing there’s lots more life in the hulls.

Overall, the fleet has a wealth of data on how to keep hulls, mechanical components, and engineering systems (HME) functioning over the decades, Moore said: “Steel hulls, we know a lot about them.”

What about the aluminum Independence Littoral Combat Ships? The Navy is looking hard at how to streamline maintenance for them, Moore told reporters after his public remarks. Because of the Navy’s inexperience and uncertainty regarding aluminum hulls, the original plan was to put Independence LCS in drydock every time they came in for major maintenance — about very three years — and inspect them from the keel up. That would require a lot of labor and tie up scarce drydock space, however, and Moore is increasingly convinced it isn’t necessary. It might be possible to double the time between drydock inspections, he and his staff said.

While Moore is working to reduce the amount of maintenance required by the aluminum Independence, however, the amount of maintenance required by the fleet as a whole will increase. If you want to keep ships longer, you have to care for them better. That’s a challenge when ships are being driven hard and maintenance yards — both Navy and private sector — are struggling to keep up.

Since 2011, Moore said, the average major maintenance “availability” has run 40 to 60 days late. Each ship that runs late has a knock-on effect on the entire fleet. When maintenance takes too long, ships take too long to get back to sea, which means ships currently on patrol have to stay out longer, which means those ships need a longer time in maintenance when they come back, creating a vicious cycle.

What’s more, because of past budget cuts and continuing uncertainty over the potential return of Budget Control Act caps, private shipyards are reluctant to hire new workers and build new facilities on the scale the Navy requires. Faced with the choice of paying a penalty for running late on maintenance, or hiring enough workers to get done on time but not necessarily having enough contracts to pay them next year, Moore said, managers often decide the penalty is the lesser evil.

All told, the admiral estimates that the industrial base is operating roughly 25 percent under its potential maximum capacity. And that’s with its current facilities, which are often old and need improvement. A recent study of one yard, he said, found the workforce collectively walked “the circumference on the Earth,” almost 25,000 miles, every single day, eating up about 6 percent of their time. Reorganizing and relocating workshops could make the yard much more efficient — if you could find the money to do it. “Throwing more people at the problem” won’t fix the shortfall without capital investments, Moore said.

The Navy’s put forward a 20-year, $21 billion plan to improve the public sector naval shipyards. That figure doesn’t include corresponding private sector investments. “It’s not cheap,” Moore acknowledged, “(but) that capacity has got to be there or else this 355 plan is not going to work.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.