ITEP: GAO Okays Army Picking Riskier Engine – Will Congress?

Posted on

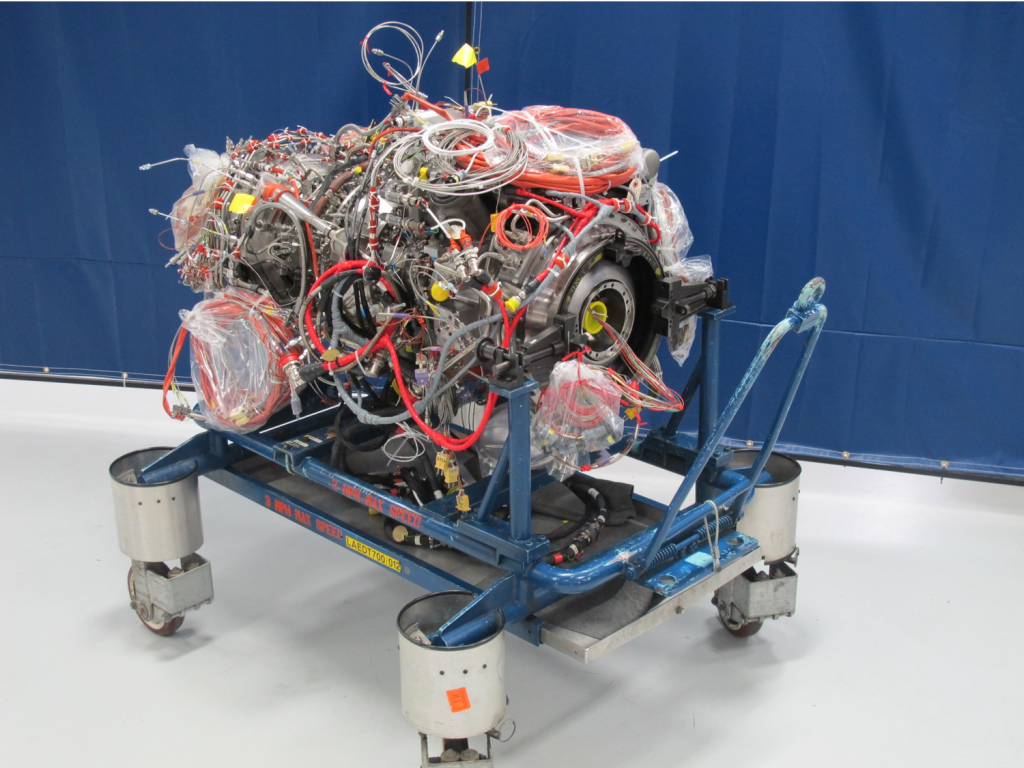

ATEC concept for their T900 Improved Turbine Engine

WASHINGTON: The Army rated GE’s proposed engine for Army Black Hawk and Apache helicopters as technically superior to rival ATEC’s, a Government Accountability Office report revealed Wednesday. That contradicts ATEC’s claims. But the GAO document unequivocally supports ATEC’s other argument for reopening the Improved Turbine Engine Program competition: By the Army’s own judgment, GE’s proposal does run a significantly higher risk of cost overruns or delays than ATEC’s.

(This is counterintuitive, by the way: ATEC proposed a more complex dual-spool design, GE a more traditional and simpler single-spool engine).

An Army maintenance test pilot checks out the engine on a Black Hawk helicopter.

So while the report is a mixed blessing for ATEC — a joint venture of Honeywell an Pratt & Whitney — it overall strengthens their case to Congress. ATEC is asking legislators to overturn the award to GE and fund continued competition. Specifically, they argue it’s too risky to make the award to GE now, when neither company has built and tested a production-representative engine, as opposed to prototypes lacking key features like built-in flight and fuel controls. GE argues 12 years of testing demonstrators and prototypes is enough.

Last week GAO ruled against ATEC’s protest and reaffirmed the award to GE. But, as emphasized in the full report released today, GAO rules on strict legal and procedural grounds: Its endorsement means only that the Army followed the rules, not that it made the right decision.

GAO “will not reevaluate proposals, nor substitute our judgment for that of the agency,” the report states. “Rather, we will review the record to determine whether the agency’s evaluation was reasonable and consistent with the stated evaluation criteria and with applicable procurement statutes and regulations.”

Congress can consider the bigger issues: Did the Army choose the right engine? How confident can we be that GE’s higher-risk proposal will work out? And is it worth spending as much as $693 million extra to let ATEC build its own set of test engines as a backup plan on a multi-billion-dollar program?

Views of the General Electric T901 Improved Turbine Engine for Army helicopters

ATEC vs. The Army

ATEC makes two essential arguments: Their design was better than GE’s and they were likely to screw up. “We felt we were rated better technically and we were rated lower risk,” ATEC president Craig Madden told me in an interview.

Well, no. Yes, the Army’s official chart summing up the comparison between the two engines seems to give ATEC higher scores in both technical excellence and risk. But the actual text of the Army evaluation — not publicly released but excerpted at length in today’s GAO report — says that “GE offered a stronger technical proposal overall which is more advantageous to the Army than ATEC’s, even with a moderate level of risk.”

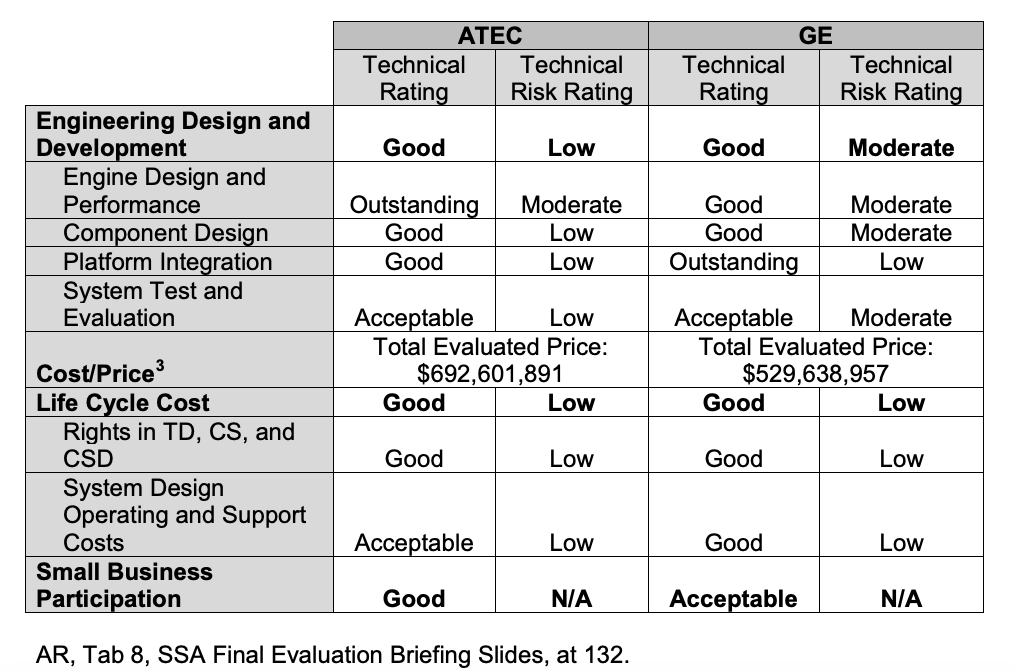

The source of the confusion? Here’s the Army’s summary chart:

Official Army chart summarizing GE and ATEC proposals for the Improved Turbine Engine Program

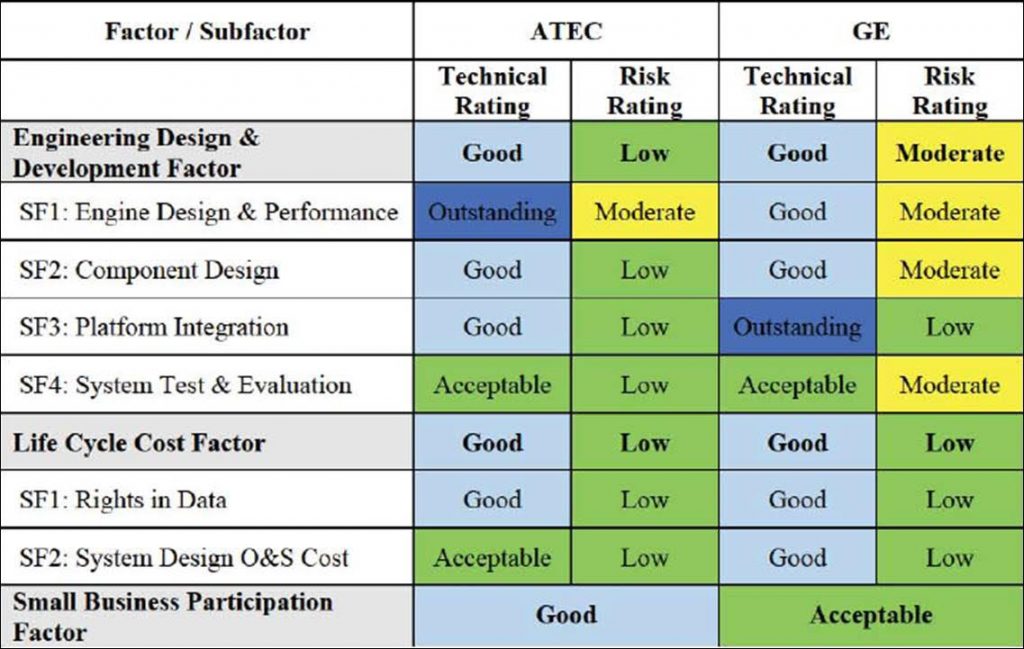

Now, here’s ATEC’s handy color-coded version, which the company circulated on Capitol Hill. Note ATEC omits the cost figures — the one area where they clearly lost — ostensibly because they were proprietary. (Maybe true, but now moot, since GAO has released them).

ATEC’s edited version of the ITEP summary chart

The Army chart implies that ATEC at least tied on its “technical rating” for both “Engineering Design and Development,” the No. 1 priority, and “Life Cycle Cost,” which is No. 3: Both companies got a score of “good” in both categories. Since ATEC even got an “outstanding” in the highest-priority subcategory, “Engine Design & Performance,” it makes sense the company would interpret that as a win.

But the text of the Army report explains those adjectives are approximations, not the actual score. (It’s similar to how two students can both get an “A” but one still scores higher because they got a 94 to the other’s 93). It’s worth quoting the Army at some length:

“Looking past the adjectival ratings… even though GE and ATEC would deliver engines with very comparable performance, GE offered a stronger technical proposal overall which is more advantageous to the Army than ATEC’s, even with a moderate level of risk,” the Army decision says.

UH-60 Black Hawks

“GE’s evaluated cost/price is 23.5% less than that of ATEC, and GE’s proposal was found to be more advantageous to ATEC’s with regard to the third most important evaluation factor [life cycle cost]. Giving due consideration to ATEC’s advantage in the least important factor [small business participation], GE has distinct advantages in each of the three highest weighted evaluation factors,” the unnamed Army Source Selection Authority writes. “Even considering the relatively lower risk of ATEC’s technical proposal, I find that this lower risk and the identified [small business participation] advantage is not worth… a 30.7% price premium.”

But what about that risk factor that keeps coming up? Well, the “moderate risk” assessment for much of GE’s proposal, in contrast to the “low risk” for most of ATEC’s, officially refers to “significant weakness or combination of weaknesses which may potentially cause disruption of schedule, increased cost or degradation of performance[, but] special contract emphasis and close government monitoring will likely be able to overcome any difficulties.” In other words, the Army said and GAO reaffirmed, the higher level of risk is probably manageable and therefore didn’t outweigh GE’s superiority in other areas.

Congress, however, doesn’t have to agree. ATEC’s counting on it.

GE’s prototype of its T901 turbine, selected by the Army for its Improved Turbine Engine Program (ITEP)

The Risk Factor

“Our goal was to go as low-risk as possible,” ATEC’s Madden told me, “and we felt we achieved that.” The Army rated ATEC’s Engineering Design & Development proposal as low-risk in three of the four subcategories; GE was “moderate” in three out of four.

GE counters that the company has built and tested two working engines for the Advanced Affordable Turbine Engine demonstration that preceded ITEP — as did ATEC. GE also built a third engine, a more refined prototype, at its own expense — something ATEC didn’t do (nor did the Army require it). These three engines, GE argues, reduce the risk dramatically.

ATEC disagrees: All three lack key features that can be difficult to develop.

In the demonstration phase, “the intention was really to demonstrate the turbo machinery,” ATEC’s senior engineer, Jerry Wheeler, told me. As GE told me earlier, that machinery — the core of the engine — is “extremely similar” between the demo and the final design, he acknowledged: “The only difference would be minor tweaks to some of the blade and vane designs.”

AH-64E Apache

But, Wheeler continued, neither the demonstrators nor GE’s self-funded prototype had all the features required to actually fly. They were covered with instrumentation and installed on test stands, which provided their fuel, lubricants, and flight controls, he said. An actual flyable engine would need almost all the instrumentation taken out and the missing systems put in — all of them made compact enough to fit in a helicopter’s engine housing and tough enough to endure the heat and vibration of a turbine in flight. Just programming the final software to run the entire system in a real helicopter, as opposed to a test stand, is “a significant technical challenge,” he said.

Now, the Army is currently confident GE can overcome those challenges in the upcoming Engineering & Manufacturing Development phase. But the service had earlier gone back and forth on whether it would let both competitors go through EMD — considered best practice to reduce the risk of one company having unexpected technical problems — or economize by downselecting to one winner at an earlier phase. ATEC wants to go back to the both-companies-get-EMD-funding plan.

Of course that costs more. It would more double the cost of the EMD phase to let ATEC build and test their engines all the way through to flight testing In the Army’s official assessment, the estimated cost of GE’s EMD proposal was about $530 million, well below ATEC’s $693 million.

In ATEC’s current pitch to Congress, however, the company isn’t asking for all of that. “We are not recommending that the Army take both companies all the way through the EMD program,” Wheeler told me. But surely, he argued, the service could afford to build “the first few engines” from both companies to get more refined test data than was possible with prototypes and demonstrators.

The expense of the additional testing, ATEC argues, pales besides the potential cost of getting the whole program wrong. “We believe that the Army could get [the additional data] for about one percent or so of the ultimate life cycle cost of the engine,” Wheeler said. “I know that’s a pretty fuzzy number, but ….it’s a pretty small price to pay, a pretty small additional investment to make to ensure that the warfighters get the best possible engine that’s going to be flying around for the next 50 to 60 years.”

Of course, it’s easy to argue for an investment in the abstract. The hard part will be taking the required millions of dollars — probably hundreds of millions — away from other programs in an Army budget that’s already been repeatedly and rigorously scoured for savings, even in top-priority technologies like hypersonics.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.