Industry Can Build 355 Ships, But Which Ones?

Posted on

Nuclear carrier USS Ford (CVN-78) at Newport News Shipbuilding

WASHINGTON: Sure, American industry can build the 355-ship fleet both Trump and the admirals want, three former Navy Secretaries said today. We can even build it a lot faster than most experts expect, but there are a lot of ifs. If we start using small shipyards that currently don’t build warships. If we streamline procurement, and, of course, If Congress can finally bust Budget Control Act caps on spending. Those three obstacles, of course, have defied reformers for years.

And after we do all that, we still might not have the right 355 ships, two of the secretaries warned. Those small yards can build small vessels like the Littoral Combat Ship, but they will struggle to build large, complex combatants like destroyers. They definitely can’t build nuclear-powered submarines or aircraft carriers, the crucial capital ships of modern naval warfare.

If we mainly want a fleet for global presence patrols, that bottleneck doesn’t matter much because we can do that job with low-end warships. If we want to deter Russia and China with their rapidly modernizing militaries, however, we need high-end ones. The Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. John Richardson, has called for a stunning 38 percent increase in the attack submarine fleet in particular. What mix of ships we need ultimately depends on our strategy — and, so far, we don’t have one.

Three nuclear-powered supercarriers — Reagan, Roosevelt, and Nimitz — and their escorts exercise together in the Pacific.

Lehman: Yes, We Can

“We can build it and we can build it fast,” John Lehman, Reagan’s hard-charging Navy secretary, said of the 355-ship fleet. “Of course, we can get there. In World War II…. we ended up building 5,000 ships in three-and-a-half years.” Hasn’t American manufacturing deteriorated since? No, said Lehman, an investor in the shipbuilding industry himself. “I think we have a better industrial base.”

Navy Secretary John Lehman (in orange) talks with naval officers aboard the USS Eisenhower in 1983.

That base is broader than the “Big Five” shipyards, all owned by either Huntington-Ingalls Industries or General Dynamics, which Lehman called an uncompetitive “duopoly.” Lehman’s own firm has bought four small shipyards over the years, all onetime warship builders that got out of the business. All four could build warships again, he said, if they could count on sustained funding from Congress and less bureaucracy from the Pentagon. Of course, attaining either of those things is not easy.

“One of the main reasons yards like that don’t bid is because they know the Pentagon system is out of control,” Lehman said, “(but) all of this is fixable.”

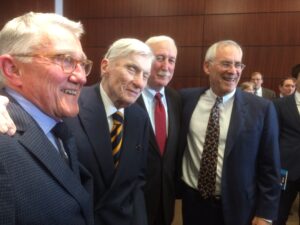

Former Navy Secretaries John Lehman, John Warner, Sean O’Keefe, and Richard Danzig (left to right)

How? I asked him after the three ex-secretaries’ public remarks at the Center for Strategic & International Studies. “You need leaders that are supported and backed up and given the authority to say ‘no,’ just ‘no'” to the bureaucracy, Lehman told me. (Lehman has a particular loathing for “the insane joint system” created by the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act, which he fought). It was bureaucratic meddling, he argued, that led to early overruns on the Littoral Combat Ship program. Intended to bypass the usual procurement process by using Other Transaction Authority and R&D funding, LCS ran afoul of traditionalists who rejected the use of private-sector construction standards and imposed stricter naval rules, he argues. (Traditionalists argue the civilian standards made the ship too vulnerable to battle damage).

LCS remains controversial to this day, but it’s a vital test case for Lehman, because it’s built by pair of smaller yards that entered the warship business in the last 20 years: Austal in Alabama and Marinette Marine in Wisconsin. The problem with applying this model more widely, however, is that the LCS is cheaper, smaller, and less complex than any other warship. You can build a 355-ship fleet more affordably with lots of Littoral Combat Ships, but is that the right fleet?

LCS-9, the future USS Little Rock, awaits launch.

Danzig & O’Keefe: Wait A Minute

If you go to small yards for small ships in large numbers, you’ll short-change the big ships needed for a big war, argued Richard Danzig, Navy Secretary under Clinton. “Fundamentally, the rationale for the Navy, the importance of the Navy to this republic, is the ability to fight even when we get into a major conflict…. If you raise the flag of 350 or 355 ships as the measure of our well being.. we will motivate people to build more and more at the low end and less and less at the high end, and it’s the high-end capability that we need.”

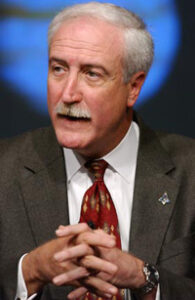

Sean O’Keefe

“350 ships or any number you choose is a bumper sticker,” agreed Sean O’Keefe, who served as Navy Secretary under George W. Bush (and ran NASA for H.W.). The right number and mix of ships needs to derive from some kind of strategy, he said, “which has yet to be really articulated in this administration.”

Can industry ramp up to build 355 ships? Sure, Danzig and O’Keefe agreed. But if you’re asking that, “you’re asking the wrong question,” O’Keefe told me. A better question, is “what kind of ships you’re looking for?

“It really does begin with the proposition of what is it you’re trying to scale to and what are the capabilities you’re looking for…which you don’t know,” O’Keefe said, because there’s no strategy. “When you get merely a numeric target, that doesn’t tell you much of anything.

“If you’re saying there’s a fixed number of low-(end) vessels, there are any number of different yards that can scale in relatively short order to accommodate that,” he said. “If you’re looking at the high end” — such as an Aegis destroyer, let alone a nuclear-powered vessel –“you have a much smaller number (of yards).”

Richard Danzig

“You would need to invest in transforming it (the industrial base),” Danzig told me. “That’s something I think we can do.” You’d need not only to expand the capabilities of the smaller yards, but diversify the bigger ones.

“I’m not saying we ought to make this huge investment,” Danzig hastened to say. “I’m just saying, if you want to go down the path that John is urging, (it’s possible). If you’re talking about a long-term building program — as inevitably you are — you can ramp up the industrial base.”

The industrial base isn’t the problem, Danzig and O’Keefe agreed. It’s everything else. In particular, it’s the money. Even if the Navy gets the funding for 355 ships of whatever kind, it also needs money to man and maintain them, or else you get a large but low-quality “hollow force.”

Crews must be recruited, trained, and given time to rest between deployments. Ships must be repaired, upgraded, and overhauled, all requiring significant time between deployments. And all these bills must be paid year after year after year, for 25, 30, 40, or 50 years (for LCS, submarines, destroyers, and carriers respectively) after the initial, crowd-pleasing contract to build the ship is signed.

The USS Warner under construction in Newport News, one of the last two shipyards in the US able to build a nuclear-powered submarine.

The Experts: Strategy & Budget

After the three ex-secretaries spoke, I sought comment from a wide array of sources in and out of government. What I learned: Speeding up shipbuilding is a lot harder than Lehman made it look. Smaller yards can build smaller ships or the less-complex components of bigger ones, freeing up the major yards for the hardest tasks. But there will still be chokepoints in production, particularly of nuclear-powered vessels, and we still need a strategy to make sure we buy the right ships.

Jerry Hendrix

“I do agree with the use of non-big five yards,” said Jerry Hendrix, a retired naval officer now with the Center for a New American Security. “The only way to get going fast is to engage the entire industrial base.

“We are not yet close on the strategy, though,” Hendrix continued. “The Navy really hasn’t engaged in a true strategy review since the Maritime Strategy appeared during the Reagan administration, (and) we need a new comprehensive review of our naval strategy prior to really going full force into a large shipbuilding program.”

Bryan McGrath

“Secretary O’Keefe got it exactly right,” agreed Bryan McGrath, a retired Navy officer now with the Hudson Institute. “The administration has not made the case for a larger Navy than we have today, though that case is eminently makeable.”

“I think there was some serious hand-waving by all three panelists (about how) the industrial base could flex to meet the requirements of the larger Navy,” McGrath went on. Lehman’s comparison to World War II is particularly misleading, he said. Not only did the US of 1941 have a vastly larger commercial shipbuilding industry, those commercial shipbuilders could convert to military production relatively easily because warships of the time were much less complex.

“Smaller yards can do the new frigate or the LCS,” a congressional staffer told me. “The real bottlenecks…are submarines and carriers. We cannot easily, quickly, or cheaply certify another yard to build these ships, so I think that is a non-starter.”

Ultimately, the real limiting factor is simply money, the staffer said: “This is far and away more about budgetary increases than anything else.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.