Hypersonics: Army Awards $699M To Build First Missiles For A Combat Unit

Posted on

Dynetics concept for their Common Hypersonic Glide Body (C-HGB) for both the Army and Navy. The Air Force will use a similar but not identical glide body.

WASHINGTON: Yesterday, the Army awarded two key contracts to catch up to Russia and China in the race to field battle-ready hypersonic missiles. After years of one-off experimental prototypes, the US plans to produce and field actual weapons.

- Dynetics won $351.6 million to build at least 20 Common Hypersonic Glide Bodies for both the Army and the Navy. Some components will go to the Air Force as well.

- Lockheed Martin won $347 million to integrate at least eight of those glide bodies with guidance systems, rocket boosters, protective canisters, and so on, arming a battery of four Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) launchers.

- Both contracts use Other Transaction Authority (OTA) to bypass much of the usual procurement bureaucracy and get the weapons to troops faster.

Yes, these weapons are still technically prototypes, since the Army expects to refine the design based on feedback from soldiers in the field. But the service’s rapid acquisition chief, Lt. Gen. Neil Thurgood, has said the four-launcher battery will be an operational unit, focused on field tests and experiments but available for combat in a crisis by 2023.

Sandia National Laboratories glide vehicle, the ancestor of the new Army-built Common Hypersonic Glide Body

Joint Force

The Army, Navy, and Air Force are working closely together on hypersonics, so the Dynetics’ contract, although awarded by the Army, will provide at least some components for all three services. The Marine Corps, as part of the Navy Department, doesn’t have their own hypersonics acquisition program, but they’re likely to end up using the Army’s land-based version.

Specifically, Dynetics is building the Common-Hypersonic Glide Body (C-HGB). That’s the part of the missile that breaks off from the booster after launch and skips nimbly in and out of the atmosphere, maneuvering nimbly at Mach 5-plus. The idea is to combine the blistering speed of a ballistic missile with the agility of a cruise missile, defeating enemy missile defenses.

The Army and Navy will use identical glide bodies — hence “common” — but the two services will integrate them with different booster rockets and packaging to meet the radically different demands of launching from a truck versus a submerged submarine. The Air Force version, which has to fit on an aircraft and launch in flight, needs a different glide body, but it should still use 70 percent of the same components.

Lockheed Martin’s newly announced contract, by contrast, is solely for the Army’s land-based version, the LRHW. That said, Lockheed already got a $480 million contract with the Air Force to build their variant, the Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW). And Lockheed has an ever larger contract, $928 million, to build a different kind of hypersonic system, also for the Air Force, called the Hypersonic Conventional Strike Weapon (HCSW). That makes the aerospace titan — already the largest defense contractor on the planet — the leading company in this rapidly growing field.

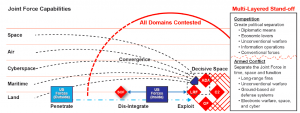

SOURCE: Army Multi-Domain Operations Concept, December 2018.

Army Challenges

While all three services are urgently fielding hypersonics, the Army is the one that’s furthest outside its comfort zone. It hasn’t had any weapon with such a long range since the Pershing II missile of the Cold War. But the Army fears its sister services won’t be able to provide round-the-clock air support in a war with Russia or China, which have invested heavily in advanced anti-aircraft defenses.

So the Army has decided it needs its own land-based weapons with ranges up to 1,400 miles. Such Long Range Precision Fires are the service’s No. 1 modernization priority. When fielded, they’ll be central to the service’s new concept for high-tech, high-intensity warfare, Multi-Domain Battle, which envisions the Army expanding beyond traditional ground force vs. ground force battles to assist the other services in the air, sea, space, and cyberspace.

The Army’s streamlined fielding of prototype hypersonic weapons is also just one example — albeit the most urgent one — of the service’s attempt to overhaul its notoriously creaky acquisition system. Traditionally, the Army bureaucracy spent years refining formal requirements on paper and in PowerPoint, then laboriously developed a weapon to those rigid specifications, only to discover — if the drawn-out process didn’t go so badly over budget and behind schedule it got cancelled — that real soldiers actually needed something different. Today, the newly created Army Futures Command pulls together experts from different bureaucratic fiefdoms to develop an imperfect but workable weapon as soon possible, then get it rapidly to real soldiers so they can give feedback on how to make it better.

Repeated cycles of field-feedback-fix are supposed to get the Army the technology it needs on a budget and a schedule it can afford. Actually doing this, of course, is a tremendous challenge. The military doesn’t just need faster missiles: It also needs faster bureaucracy.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.