From Skywarrior To UCLASS: Back To The Future Of Carrier-Based Strike?

Posted on

Lockheed Martin’s UCLASS concept.

WASHINGTON: Overstretched as they are, the Navy’s 10 aircraft carriers remain unequalled icons of American might. But the ugly truth is they’re not as mighty as they might be.

The maximum range of carrier-borne strike aircraft has eroded over the last quarter century. Even the Navy’s future fighter, the F-35C, will have an unrefueled range of about 600 nautical miles: That’s one-third the range of the old A-3 Skywarrior, which entered service in 1956. Navy F-18 Hornets striking targets in Afghanistan had to refuel repeatedly from lumbering aerial tankers — but that option is not available in airspace contested by enemy fighters or anti-aircraft missiles.

Senate Armed Services chairman John McCain and the outspoken chairman of the House subcommittee on seapower, Rep. Randy Forbes, want to solve this problem with a long-range drone: the UCLASS, short for Unmanned Carrier-Launched Surveillance & Strike. An unmanned aircraft can fly longer, take greater risks, and boast a smaller radar profile than one burdened with a human pilot. But the Navy has proposed a UCLASS that’s optimized for long-range reconnaissance, with limited capability to penetrate so-called anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) defenses and to strike a well-defended target.

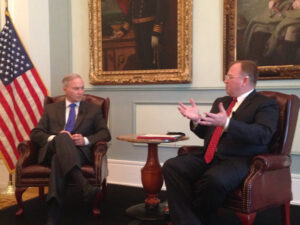

Rep. Randy Forbes (left) and Capt. Jerry Hendrix (USN, ret.) (right) at the Army & Navy Club today

“If my priority is it’s got to get through an A2/AD defense, and I’m building something that couldn’t possibly get through an A2/AD defense, I know from the beginning I’m wrong,” Forbes said this afternoon at the Army and Navy Club here in DC.

“What do we want this thing to do?” Forbes said. “I want it to drop some pretty heavy stuff on some pretty bad people.”

“The thing that bothers me most is that we’ve taken a lot of thoughts off the table,” the congressman continued. The Navy’s proposed requirements insist on at least 14 hours of unrefueled endurance, which is ideal for long reconnaissance patrols. But 14 hours forces trade-offs favoring fuel load at the expense of bomb load and fuel-efficient flight at the expense of stealth. We need to relook those requirements, Forbes said.

The Office of the Secretary of Defense agrees, at least enough for the UCLASS requirements to be repeatedly delayed by reviews led by the powerful Deputy Secretary, Bob Work.

“We’ve had an RFP (Request for Proposals) ready to go for a year and a half, two years now, and it’s been held up because of a look at overall ISR [intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance] systems,” Navy Secretary Ray Mabus said last week at the American Enterprise Institute. “One of the reasons we’d like to go ahead and get the RFP out is that we’d like to find out what’s available out there in industry.”

The Navy staff’s director of air warfare, Rear Adm. Mike Manazir, put it more bluntly to reporters last week: “We have lost this time to put that technology to work. That’s where my frustration is.”

Forbes, of course, thinks OSD is just taking the time to get this right. Many dissidents inside the Navy Department agree with him, he said. “The Navy’s very divided on this,” Forbes said, “and there are many people in the Navy that concur with us and think the questions we’re asking are appropriate questions.”

Mabus argues that the technology (and the budget) probably aren’t ready to build a UCLASS that can do the deep-strike mission. “The way I’ve always seen UCLASS is as a bridge between where we are today and a full-up … autonomous strike UAV in contested areas,” he said at AEI.

Forbes has no patience for the “bridge” analogy. . “If you don’t know what that [future] platform’s going to look like, then you basically have a bridge to nowhere,” he said today. “When you ask them, ‘well, where’s the bridge leading? What is that platform going to look like?’…. then all of a sudden the mike goes quiet.”

Forbes and other advocates of a deep-striking UCLASS argue the current carrier air wing is too short-ranged, potentially requiring the valuable flagships to sail so close to their targets that they become vulnerable to shore-landed anti-ship missiles. The irony here is the Navy used to have a long-ranged carrier strike capability. But it gave it away in the 1990s, when it retired the 1,000-mile A-6 Intruder and cancelled its troubled replacement, the A-12.

“The A-3 came online in the early to mid 1950s, and for most of the next fifty years the Navy was able to do long-range deep strike,” said retired Navy captain Jerry Hendrix, who moderated today’s discussion with Rep. Forbes. Most of those old strike aircraft had an unrefueled range of 1,000 to 1,2000 miles, he told me after the event, but the A-3 itself “had a range of 1,800 nautical miles — unrefueled — and could carry a 12,000-pound atomic bomb.”

“If you look at the A-3 Skywarrior….that plane was the reason why we developed the Forrestal-class, the first super-carrier, [in the first place],” said Hendrix, who’s writing a study of carrier air wing evolution at the Center for a New American Security. The 1,000-foot flight deck of a modern carrier was originally designed to give large, long-ranged jet aircraft room to take off. Its massive maintenance spaces and ordnance storage were originally intended to support heavy bombers, not just strike fighters. As anti-aircraft and anti-ship missiles get more threatening, it may be time to use the super-carrier for its original purpose again.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.